20 years after Hurricane Katrina, St. Bernard Parish is still recovering

CHALMETTE, La. — When Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Louisiana on August 29, 2005, Louis Pomes was standing on top of a St. Bernard Parish government building that overlooked a marsh.

“All of a sudden it just looked like somebody picked up the earth and started running with it,” Pomes remembers. “It was a surge of water coming, but it was pushing all the debris and the trash in front of it.” At the time he worked for the parish as a heavy equipment supervisor.

Katrina flooded nearly every building in St. Bernard Parish, just east of New Orleans. Twenty years after the storm, oil and sugar refineries are back, but the local population is just two-thirds of what it was before Katrina. This sprawling, blue-collar coastal community is still rebuilding and it’s getting more optimistic about the future.

New flood prevention measures are in place as part of a regional $14.5 billion federally-funded flood protection system. But at just a few feet above sea level, St. Bernard Parish faces a future in which climate change makes hurricanes more intense and flooding more severe.

Deciding whether to return

In December 2005, NPR first talked with Kevin Potter outside his home, in the parish town of Chalmette. It was flooded with about three-and-a-half feet of water and was not habitable. His family was staying in an apartment about 100 miles away, near Baton Rouge, while they waited for a FEMA trailer to show up so he could move back to his property.

“Hopefully we’ll be back within a couple of weeks and start to remodel the house,” Potter said at the time. But first he wanted assurance that two things would happen: the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet (MRGO) had to be closed and stronger levees constructed around the township.

The MRGO, known locally as the “Mr. Go,” was a shipping channel that was a shortcut from New Orleans to the Gulf of Mexico. During Katrina, it channeled storm surge into the parish. The channel was closed in 2009 and a 22-mile levee system around St. Bernard Parish was completed in 2018.

Two decades later, Potter, now 71-years-old, and his wife are back “and we’re still fooling with the house. You know we’re almost there — about 90%.” On top of basic repairs, they decided to remodel. Among the few items left to do: the living room floor is bare concrete and the back wall still needs a brick exterior installed.

Rebuilding was more expensive than Potter imagined. His wife’s daycare business was the first priority, because it brought in money that helped pay for home repairs.

“I built the daycare center and I had all the receipts,” he says. Potter doubled that cost to come up with an estimate, but “everything was coming back triple.” Supplies and labor were more expensive because everyone needed them at the same time.

Now Potter says he’s comfortable they are prepared for future hurricanes. In this politically conservative community, people don’t connect more intense storms, like Katrina, to climate change, as scientists do.

Potter says if the new levees hold “I think we’ll be okay, because Katrina was the worst of the worst.”

The cost to rebuild and the risk of future storms were too much for some St. Bernard Parish residents. They left and never returned. Census estimates show the population was 71,300 in 2005 and then collapsed to 16,563 the next year. Since then, the number of people returning and moving into the parish has slowly risen to 44,783 last year.

Loading…

Mark Benfatti was among those who left after Katrina, “I had three feet of water on my second floor, so I think I estimated 12 to 13 feet of water inside of our house in Saint Bernard.”

Benfatti says he owned four restaurants in the parish that also flooded during Katrina. His family moved north, across Lake Pontchartrain, to Mandeville, mostly because his elderly mother-in-law needed to be close to an operating hospital. The only hospital in the parish was damaged during the storm and later condemned.

Now, Benfatti lives an hour’s drive from the parish in Bay St. Louis, Miss., where he owns a construction company. He thinks surviving the next big storm will be easier in his new town. While most of the parish is only a few feet above sea level, his current neighborhood is on higher ground.

“Where I’m at now, it’s going to take 22 feet of water before you even get to my house. I just think that’s a little bit better chance,” Benfatti says.

Rebuilding the parish and the population

Drive through St. Bernard Parish now and there’s more green space — gaps in neighborhoods where houses used to stand. Satellite images, before and after Katrina, show swaths of neighborhoods where flooded houses were torn down and never rebuilt.

Loading…

Louis Pomes, the former heavy equipment supervisor, was elected parish president in 2023. He says many residents left after the storm because there were no schools, healthcare facilities or grocery stores.

“I mean for three months you couldn’t spend a copper penny in Saint Bernard Parish. There was no way to spend money — there was nothing in operation,” Pomes says. Then more residents returned as rebuilding got underway and new residents arrived.

“We had a lot of people from different states that came in to help rebuild, and some of them never left,” Pomes says. “We have a lot of new families that moved into Saint Bernard Parish, which were thankful for that.”

There are fewer white residents now and more Black and Latino people, according to Census estimates. That’s despite a parish ordinance that homeowners could only rent to blood relatives. NPR reported on legal challenges to the ordinance in 2009. A judge ruled that was illegal discrimination and the law was rescinded as part of a 2014 settlement.

“That cost St. Bernard Parish a lot of money,” says Pomes. There was a $1.8 million dollar settlement with the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Action Center and a $2.5 million settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice in 2013.

Now Pomes says he’s focused on attracting new residents to the parish.

“That will be really awesome if we can get at least another 20,000 more residents in Saint Bernard Parish,” Pomes says. That would put the community’s population back to almost the level it was before Katrina.

With a rebuilt hospital, new schools and a plan to attract more businesses to the parish, Pomes is optimistic. So is 22 year-old Belle Landry, who works in her family’s business.

“Like any New Orleans restaurant, we have red beans on Monday,” Landry says, as workers recently put stools up on tables at Arabi Food Store’s afternoon closing time. Above the front door, a small plaque shows how high the water reached during Katrina — about 7 feet.

Landry was two years old when Katrina hit. She says her family returned to St. Bernard Parish as soon as they could, later buying this combined store and restaurant. She says talk about future storms does make people nervous but improvements, like the updated levee system, help calm fears.

“I feel safe in my community and I love the culture here. The people, they definitely have a resilient spirit,” Landry says.

St. Bernard Parish residents and leaders hope that will, eventually, bring the community fully back, 20 years after Hurricane Katrina.

On August 29 this year, the parish plans to mark the day with a mass at Our Lady of Prompt Succor Catholic Church, followed by an annual reading of 164 names of those who died in the storm. That will take place, as it does every year, at the Katrina Memorial in the fishing village of Shell Beach, La.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

Hurricane Katrina flooded nearly every building in St. Bernard Parish, east of New Orleans. Twenty years after the storm, oil and sugar refineries are back, but the population has not recovered. NPR’s Jeff Brady reported from St. Bernard Parish back in 2005, and earlier this month he returned and found that the sprawling, blue-collar coastal community is still rebuilding.

(SOUNDBITE OF TOOL BANGING)

JEFF BRADY, BYLINE: When I first met Kevin Potter in December of 2005, he was at his brother’s house, which was being rebuilt.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR CONTENT)

KEVIN POTTER: We had about 2 1/2 to 3 foot of water.

BRADY: Twenty years ago, Potter also planned to rebuild his flooded home, but only if two things happened. He wanted the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet closed. That’s a shipping channel known as the MR-GO that brought Katrina’s storm surge into the parish.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR CONTENT)

POTTER: The MR-GO has got to be closed or a gate. Some type of device has to be installed. We have to correct the levees.

BRADY: The MR-GO was closed and a 22-mile levee system built around St. Bernard Parish, part of a regional $14.5 billion federally funded flood protection system. So today, Potter is back.

Hi there.

POTTER: How you doing, Mr. Jeff? Haven’t seen…

BRADY: Good to see you.

POTTER: …You in a while.

BRADY: Twenty years (laughter).

POTTER: Yeah.

BRADY: Potter catches me up. His family lived in a FEMA trailer in their yard for two years after Katrina. He was laid off from his oil refinery job. And now, at 71 years old, he worries about the cost of flood insurance.

POTTER: And we’re still fooling with the house. You know, we almost have about 90%.

BRADY: The living room floor is bare concrete, and the back wall still needs a brick exterior installed. Rebuilding was more expensive than he imagined, and his wife’s day care business was the first priority.

POTTER: I built the day care center. I had all the receipts, and I doubled it. I doubled it when I made an estimate. And everything was coming back triple.

BRADY: In this politically conservative community, people don’t connect more intense storms like Katrina to climate change, as scientists do. Still, for many, the cost to rebuild and the risk of future storms was too much. They left and never returned. U.S. census data show the parish population dropped from over 71,000 people before Katrina to about 45,000 as of last year.

Mark Benfatti was among those who left. He owns a construction company an hour’s drive away in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi.

(SOUNDBITE OF BANGING)

BRADY: This is a change for Benfatti. He owned four restaurants in St. Bernard Parish, but they all flooded, along with his home.

MARK BENFATTI: I had 3 feet of water on my second floor. So I think I estimated 12 to 13 feet of water inside of our house in St. Bernard.

BRADY: Benfatti says the parish is only a few feet above sea level, but his current neighborhood is on higher ground.

BENFATTI: Where I’m at now, it’s going to take 22 feet of water before it even gets in my house. I just think that’s a little bit better chance.

BRADY: St. Bernard Parish President Louis Pomes says many residents left after the storm because there were no schools, health care facilities and grocery stores.

LOUIS POMES: I mean, for three months you couldn’t spend a copper penny in St. Bernard Parish. There was nowhere to spend money. There was nothing in operation.

BRADY: Drive through the parish now and there’s more green space – gaps in neighborhoods where houses used to stand. The population has changed, too. There are fewer white residents and more Black and Latino people. That’s despite a parish ordinance that homeowners could only rent to blood relatives. A judge ruled that was illegal discrimination, and the law was rescinded. Pomes says that was a costly legal fight for the parish, and now his focus is on attracting new residents.

POMES: That would be really awesome if we can get at least another 20,000 more residents in St. Bernard Parish.

BRADY: With a rebuilt hospital, new schools and a campaign to attract more businesses, Pomes is optimistic. So is 22-year-old Belle Landry, who works at her family’s store and restaurant.

BELLE LANDRY: Like any New Orleans restaurant, we have red beans on Monday.

BRADY: Landry was 2 years old when Katrina hit. Her family returned to St. Bernard Parish as soon as they could and later bought this business.

LANDRY: And I love the culture here. The people – they definitely have, like, a resilient spirit.

BRADY: Residents hope that eventually will bring their community fully back, 20 years after Hurricane Katrina.

Jeff Brady, NPR News, St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana.

In Berlin, there are movies, there’s politics and there’s talk about it all

Buzz around whether the city's film festival would take a stance on the war in Gaza has dominated conversation in recent days.

Alex Ferreira wins 10th gold medal for Team USA, matching America’s highest total in Winter Olympics

Freeskier Alex Ferreira clinches a tenth gold medal for the U.S. in these Games, tying the U.S.'s all-time record for gold medals in a Winter Olympics.

Trump calls SCOTUS tariffs decision ‘deeply disappointing’ and lays out path forward

President Trump claimed the justices opposing his position were acting because of partisanship, though three of those ruling against his tariffs were appointed by Republican presidents.

The U.S. men’s hockey team to face Slovakia for a spot in an Olympic gold medal match

After an overtime nailbiter in the quarterfinals, the Americans return to the ice Friday in Milan to face the upstart Slovakia for a chance to play Canada in Sunday's Olympic gold medal game.

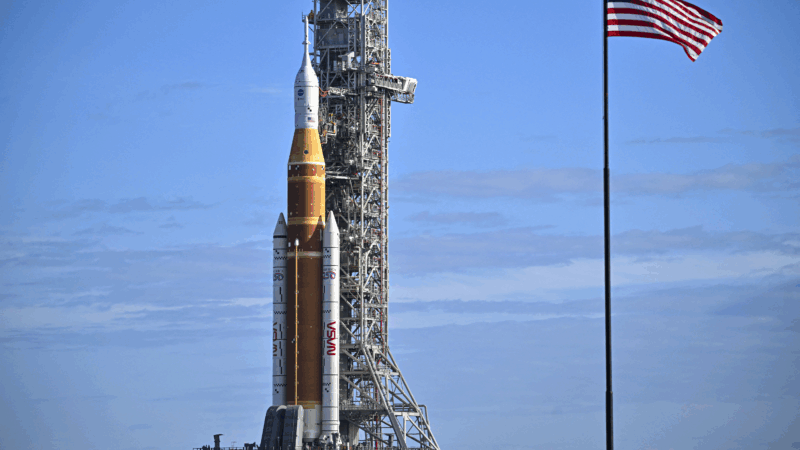

NASA eyes March 6 to launch 4 astronauts to the moon on Artemis II mission

The four astronauts heading to the moon for the lunar fly-by are the first humans to venture there since 1972. The ten-day mission will travel more than 600,000 miles.

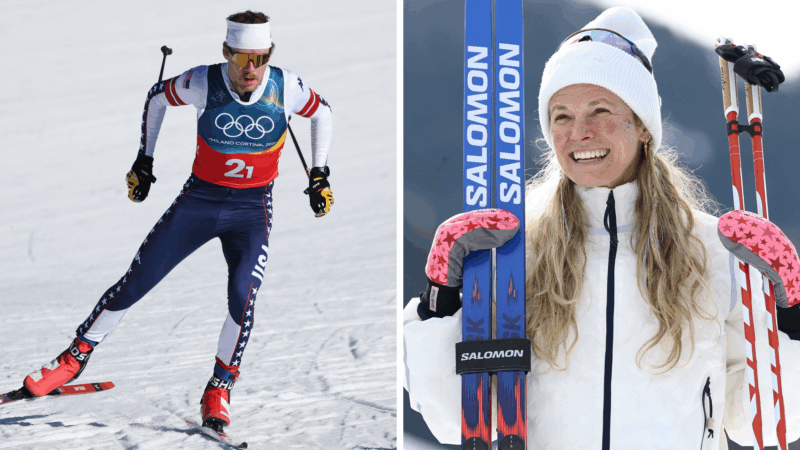

Skis? Check. Poles? Check. Knitting needles? Naturally

A number of Olympic athletes have turned to knitting during the heat of the Games, including Ben Ogden, who this week became the most decorated American male Olympic cross-country skier.