Despite Record Number On The Road, Women Truck Drivers Still Face Barriers Getting Into Industry

Pamela Williams, a truck driving instructor with DSC Training Academy, stands in front of one of the academy’s trucks. June 29, 2021

Pamela Williams has a message for the trucking men she shares the road with.

“Guys, you better watch out, ‘cause this right here is a women’s industry from now on,” said Williams, a truck driver and instructor with DSC Training Academy in Jackson, Mississippi.

That’s not true, at least not yet. More than 83% of drivers in June were men, according to the job site ZipRecruiter, but women are hitting the gas pedal and shrinking the gap.

There’s a record number of women on the road today, about 245,000 – over 2% more than there were before the pandemic. Men, meanwhile, make up about 1.2 million of the workforce — about 3% below their pre-pandemic levels.

Women are taking the wheel for good reason — trucking is in high demand, requires a short amount of training and pays better than many other fields they’ve traditionally held. Restaurant jobs also proved to be less stable than trucking, which lost fewer workers during the pandemic.

Despite these advances, it remains tough for many women to find the entrance ramp into the field. There’s sexism on and off the road, and women interested in taking the job to build a better life for their family might not be able to take it if it means leaving those loved ones behind for weeks.

A Key Motivator? Money

Stephan Bisaha,Gulf States Newsroom

Pamela Williams, an instructor with DSC Training Academy in Jackson, Mississippi, demonstrates how to drive one of the academy’s trucks. June 29, 2021

Truck drivers in June earned on average more than $26 per hour, much more than workers in many service jobs traditionally held by women, — even when counting tips.

Those restaurant and other service sector jobs also showed their vulnerability when they disappeared during the pandemic. In April 2020, 12 million women were no longer working, compared with 10 million men. Many of those were in leisure and hospitality.

“We did not see the same hit against jobs in construction, transportation, manufacturing,” said Chanda Childers, a study director with the Institute For Women’s Policy Research. “The prospects are a lot better in those jobs than in low wage service jobs where women are traditionally overrepresented, that do not pay them a living wage.”

When they first climb into the truck, most of Willams’ students — men and women — get intimidated. Everything is bigger — the mirrors, the wheel and even the gearbox, which terrifies both in its size and because most students have never driven a stick.

But once the students turn the key, change gears and feel the subtle shift in the engine’s rumble, the atmosphere transforms.

“They feel the power, then everything changes,” Williams said. “They’re like ‘Oh, oh I’m gonna be a truck driver!’”

Williams began her truck driving career seven years ago. She loves getting to see the country and the independence the job brought. But her main motivation is the same as her students’ — money.

“I could go to a job and work 40 hours and bring home $400 and I’ve been stressed out the whole time,” Williams said. “I can go out here and drive a week and make a thousand dollars – a quick thousand dollars doing something that I like to do. That’s good.”

Amalya Livingston signed up for Williams’ classes at DSC Training Academy because she saw how it helped her mom escape poverty.

“She just recently purchased a house,” Livingston said. “She’s doing really good for herself so I follow her example.”

Stephan Bisaha,Gulf States Newsroom

Diamond Herring and Amalya Livingston are enrolled in truck driving classes at DSC Training Academy. June 29, 2021

Sexism Still A Roadblock For Some

Women drivers say while sexism from the male truckers has improved over the last decade, it hasn’t gone away.

When Livingston recently climbed out of the cabin at a truck stop to refuel, some men gave her smirks, grunts and side-eyes.

“It comes with the territory,” Livingston said. “Women who make history don’t, you know — we’re not complacent.”

The judgment for women entering what’s often labeled “a man’s job” doesn’t just come from the road. It can come from friends, family and the women themselves who can’t imagine themselves in the field.

“They’re not aware that these are jobs that they actually could do,” Childers said. “In their heads it hasn’t been presented to them as an option.”

Groups advocating for women to enter male-dominated industries say there should be more wrap-around services for women like transportation and scholarships for training. While four weeks of truck driver training might be short compared to other programs, some single moms can’t afford to take the time off for their current job.

Far From Home

Possibly the biggest barrier for women remains being on the road for weeks at a time and away from the people they care for. Along with a shortage of child care spots in the country, women are also more likely to be caretakers for elderly family members.

“We’re caregivers for our children, we’re caregivers for our loved ones,” said Willie Jones, president of DSC Training Academy. “So she has to think really not just twice, but probably three times, ‘Is this something that I want to do?’”

Tiffany Hathorn initially dismissed the idea of trucking. She had other jobs and even tried to start her own business, but she says she kept hitting a financial ceiling and never made enough money to get her family where they needed to be financially. Trucking looked like a way to give her two sons the lifestyle she wanted for them, but she didn’t know what would happen to them while she was on the road.

“I just kind of threw it out of my head,” Hathorn said. “I just didn’t think anybody would be able to watch out for my boys when I’m not able to.”

Stephan Bisaha,Gulf States Newsroom

Tiffany Hathorn earned her trucking license a year ago and estimates she will make $70,000 this year. June 29, 2021

Luckily, Hathorn's mother stepped in and said she could watch the kids. Hathorn, her sons and their grandmother had lots of conversations about how to make the job work, and she only enrolled in the DSC Training Academy once she had their full buy-in.

A year later, Hathorn estimates she’s on track to make $70,000 for the year. She orders groceries from states away and video chats when she can. When she comes back once a month, she makes her son’s a priority, taking them fishing and camping.

She now gets Facebook messages from women and men asking for advice on if trucking is right for them. She tells them the good and the bad — the money has given her peace of mind while she knows it wouldn’t have been possible without her mom caring for the kids. Still, she always encourages them to try and do it.

“That’s an awful feeling when you’re struggling from check to check and dreading if anything’s going to happen like appliances going out,” she said. “But now when those issues come up, I’m just like, OK, we’ll get it done. We’ll pay for it. And that’s a huge, huge, huge, huge difference.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Birmingham, Alabama, WWNO in New Orleans and NPR.

This historian dug up the hidden history of ‘amateur’ blackface in America

In her new book, Darkology, historian Rhae Lynn Barnes writes about how blackface and minstrel shows became one of the most popular forms of entertainment in 19th- and 20th-century America.

Attempted attack with explosives in New York City investigated as “ISIS-inspired terrorism”

New York City NYPD Commissioner: "Explosive devices that could have caused serious injury or death."

Trump is using immigration policy to suppress speech, lawsuit claims

A new lawsuit accuses the administration of violating the First Amendment by threatening the visas of researchers for work on disinformation and content moderation of social media.

Why young girls are disguised as boys in Afghanistan

The Taliban has released a video of an interrogation of a girl who passed as a boy. It's an age-old practice in this patriarchal society but now appears to be happening with some frequency.

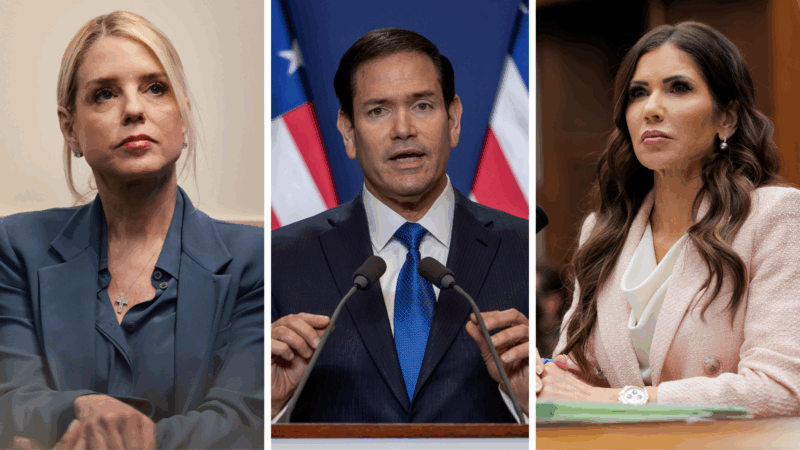

Live Nation and Justice Department reach settlement in antitrust case

The trial, which began a week ago in a New York City courtroom, aimed to break up Live Nation and its subsidiary, Ticketmaster.

Microshelters for Birmingham’s unhoused set to open soon

The pilot program called Home For All involves building 14 small pallet homes to house those who would otherwise be living on the streets.