Protecting People In Prisons, Jails And Shelters From COVID-19

The Firehouse Shelter has been around for decades, serving people throughout Jefferson County who are experiencing homelessness. Director Ann Rygiel says staff members are used to emergencies, like cold weather. But the coronavirus is unlike anything they’ve ever experienced.

“We’re kind of re-evaluating everything,” Rygiel says.

They are focused on keeping the shelter virus-free. On Tuesday, staff began checking the temperature of everyone who enters the building, including employees. Volunteers, who normally help with daily meal prep and feeding, are not allowed in.

Andrew Yeager, WBHM

Social distancing is not possible at the Firehouse Shelter dormitory.

The shelter is also capping the number of people who can stay overnight at 75, even though the capacity is 100. Rygiel says this will reduce the demand on the Firehouse’s small staff, and it will also give people more space, though less than the recommended six feet of separation.

Normally, men who stay at the shelter are asked to leave during the day, but Rygiel says for now, they are encouraged to stay at the shelter 24/7, and everyone will have an assigned bed.

She says a lot of the guys who regularly stay at the Firehouse are older, with pre-existing conditions like diabetes or mental illness.

“All of those factors kind of put us in a powder keg for a very vulnerable population,” Rygiel says.

At places like homeless shelters, where people live and sleep side-by-side, the coronavirus could spread rapidly. And certain preventative measures, like social distancing, are all but impossible. The same is true for state prisons.

More than 20,000 people are housed in Alabama’s prisons. Like people experiencing homelessness, many incarcerated people are also older, with chronic health problems. State prisons are significantly overcrowded, with hundreds of inmates sleeping together in dormitories, just inches apart. They share toilets and have limited access to hygiene products and medical care.

Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) Commissioner Jeff Dunn says the department has dealt with outbreaks before and they have an infectious disease plan.

“We’re following all the guidance that’s coming out of the state task force and the CDC,” Dunn says, “and we’re prepared to respond however we need to.”

This week, officials suspended visitation in state prisons for 30 days. For the next 60 days they are also waiving the co-pays inmates typically have to pay to visit the prison infirmary.

“In the coming days, all staff will be screened prior to entering the facilities by having their temperature taken,” reads a statement on the ADOC’s website. “If the individual’s temperature is greater than 100.4, they will be restricted from entering the institution that day. All employees will have temperature screening at the beginning of each shift statewide.”

Ensuring correctional officers and employees stay healthy is paramount, not only because the Alabama Department of Corrections is understaffed, but also as a precaution for inmates.

Experts say the primary goal in confined spaces like prison is to keep the virus from ever getting inside. They recommend limiting who comes in, and screening the people who do.

The same goes for local jails.

“We are taking preventative measures in our jails to combat the spread of this virus,” said Jefferson County Deputy Chief David Agee at a press conference on Monday.

On average, Jefferson County’s two jails house about 1,000 people, and compared to state prisons, local jails have more movement in and out of their facilities. Agee says officials are checking new inmates for symptoms and performing “intense cleaning” on a regular basis. Legal visits can continue, although with the county courthouses temporarily closed, some people awaiting trial may find themselves waiting longer than anticipated.

Nationwide, advocates are asking officials to release people from jails and prisons if they are at high risk for COVID-19. Some cities are taking this kind of action, but at least for now, it does not appear to be an option in Alabama. If someone does show symptoms, jail and prison officials say they can likely be quarantined onsite.

At local homeless shelters, it’s a different story. Firehouse director Ann Rygiel says the shelter doesn’t have the space or the ability for people to self-quarantine. She says this is especially a problem since people experiencing homelessness typically don’t have health insurance.

“Right now, we are working with the county and the city,” Rygiel says, “to try to figure out, ‘What do you do with people that are sick?’”

She says for now, if someone comes to the shelter with a fever, the plan is to send them to the hospital. Health officials advise against that, but for some, there just isn’t any other place to go.

And the Oscar goes to — wait, why is it called an Oscar?

The Academy Awards officially adopted the "Oscars" nickname in 1939. But who is Oscar, and who started calling them that? We may never know. But here are four enduring legends to consider.

TSA workers miss a full paycheck, while travelers keep paying airport security fees

Many TSA workers received no money in their paychecks Friday as the partial DHS shutdown drags on. Fees paid by airline passengers keep piling up, even as airport security officers work without pay.

How Italy became the darlings (and contenders, too) of the World Baseball Classic

With espresso shots, kisses on the cheek and Andrea Bocelli singalongs, Team Italy has charmed the baseball world. But their mission is more ambitious: Turn Italy into a bona fide baseball factory.

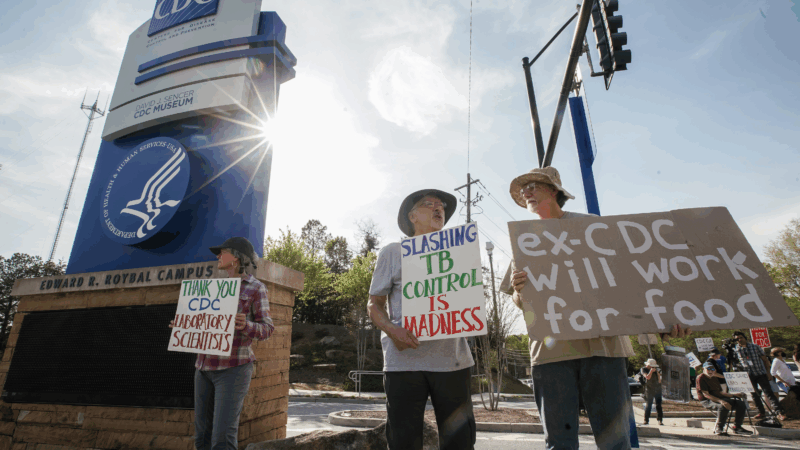

After firings, funding cuts, and a shooting, can a demoralized CDC workforce recover?

It's been a year since mass firings began at the CDC, the federal public health agency. Then came a shooting, and the government shutdown. Atlanta is still feeling the economic and emotional effects.

‘Scarpetta’ is a captivating murder mystery — and a high-wire balancing act

Based on a series of novels by best-selling author Patricia Cornwell, Scarpetta follows two different mysteries from two different timelines. It's structurally complicated — but it all holds up.

‘Derry Girls’ creator returns with a gleeful riff on the murder mystery

In the hilarious Netflix series How to Get to Heaven from Belfast, three women learn that a long estranged school friend has died in a suspicious manner — and take it upon themselves to investigate.