Program Uses ‘Horse Sense’ to Improve Communication with Police

The video begins with dramatic police footage of an incident from a few years ago. An officer questions a young boy and asks for his ID, then proceeds to handcuff him. The boy, who has autism, appears confused and screams loudly as he is pushed to the ground. The officer later says he thought the boy was using drugs.

Advocates say the incident exemplifies what can happen when law enforcement does not understand or know how to adapt to a person’s disability or difference. For kids and adults who have a communicative disorder like autism, interactions with police can escalate quickly.

The video is part of a larger training program developed by the Red Barn, an equestrian-focused nonprofit based in Leeds. It includes educational materials for law enforcement, as well as parents and teachers, on ways to improve communication between police and kids who have communicative disorders, and it uses horses to guide the way.

Recognizing a Difference

The video features interviews with experts like Temple Grandin, as well as parents and kids who talk about how to recognize the signs someone may have a communicative disorder, such as autism or Tourette syndrome.

“Part of what we hope the video does is to give the officer an overview of some of those things to look for,” says Joy O’Neal, executive director of the Red Barn.

O’Neal says there are behavioral clues, like avoiding eye contact, or stimming, a type of self-stimulation when someone repeats a movement or sound.

Bryan Kelley, a school resource officer with the Mountain Brook Police Department, says 30 years ago, he did not know anything about disorders such as autism. Today, he says there is a greater awareness and more training opportunities for police and first responders. Still, Kelley says police officers are generally trained to respond and act quickly.

“Bluntly, when somebody runs from the police, the police chase them,” Kelley says.

And in the moment, he says it can be difficult to know whether someone has special needs.

“It’s complicated when you deal with someone and you don’t know why they’re behaving in an odd manner,” Kelley says. “Maybe it’s a disability, but maybe it’s drugs, maybe it’s something else.”

Horse Sense for All

The training program not only includes tips on recognizing a person’s communicative differences, it also teaches different ways to communicate, how to approach someone and what kind of questions to ask. This is where experts turn to horses.

The Red Barn regularly uses horses to work with kids who have physical and emotional disabilities. They now also offer in-person trainings for police and invite them to participate in activities with students at the barn.

During one of these activities, students work with Officer Kelley to lead a horse through an obstacle course, but they cannot talk to each other.

For students like Kiersten Charping of Springville, the activity is a challenge.

Red Barn

Officer Kelley and Kiersten Charming tandem lead a horse through an obstacle course, without talking to one another.

“You have to realize your body language, because, like, they’re horses and they can’t speak,” she says.

At the end of the activity, students debrief with Officer Kelley to discuss what they learned and how they feel. Charping, who says she sometimes feels anxious and has trust issues, says it is fun and she enjoys working with the horses.

Red Barn director Joy O’Neal says the exercise is a chance for students to get to know police officers in a comfortable setting. And she says working with horses helps everyone take a step back and slow down.

“No matter how strong you are, you can’t overpower a horse with your own strength,” O’Neal says. “It has to be done through cooperation and understanding.”

A Greater Need

To create this training program, called Horse Sense for All, the Red Barn worked with a group based in California called the JAYC Foundation. For years, the JAYC Foundation has used horses to work with trauma victims and law enforcement. One of the founders is Jaycee Dugard, who spent years in captivity before police found her. Dugard says when law enforcement questioned her, she felt intimidated.

“Even though I didn’t have a communication disorder or a learning disability, it really felt like I had a lot of trouble communicating with officers when I was first found,” she says.

The new training program is focused on improving communication between police and kids with communicative disorders, but ultimately, both groups hope it helps improve interactions with all people, whether they are living with trauma, mental illness, or autism.

Ronald Hicks to be installed as 11th archbishop of New York

Ronald Hicks, a former Illinois bishop chosen by Pope Leo XIV to replace the retiring Cardinal Timothy Dolan, is set to be installed as New York's 11th archbishop

Iran and US set for talks in Oman over nuclear program after Tehran shaken by nationwide protests

Iran and the United States could hold negotiations in Oman after a chaotic week that initially saw plans for regional countries to participate in talks held in Turkey

Lawmakers advance restrictions on SNAP benefits

Alabama is one of the most obese states in the nation. One state lawmaker says SNAP benefits, commonly known as food stamps, could be used to turn that around. We talk about that and other legislative matters this week with Todd Stacy, host of Capitol Journal on Alabama Public Television.

New Jersey’s special Democratic primary too early to call

With more than 61,000 votes counted, Mejia led Malinowski by less than 1 percentage point. The Democratic winner will face the Republican primary winner Joe Hathaway in April.

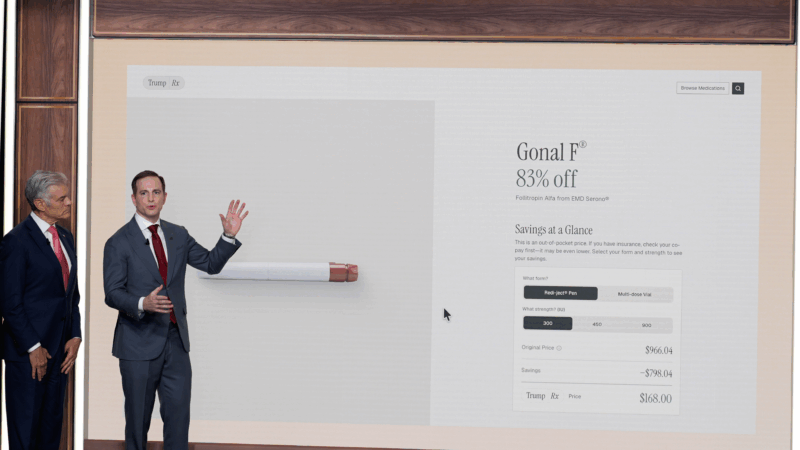

White House unveils TrumpRx website for medication discounts

Under Trump administration deals to lower drug prices, pharmaceutical companies are offering some of their drugs at discounted prices through a new website called TrumpRx.gov.

Virginia Democrats show map to counter Trump redistricting but its future is unclear

The new map still requires approval from the courts and the voters but, if enacted, it could help Democrats win four more House seats