Development Fills the Cahaba River with Sediment

Riverkeeper David Butler walks along a section of the Cahaba River in Hoover that's been especially impacted by erosion and sediment loading.

Cahaba Riverkeeper David Butler often has to convince people that sediment can be a problem.

“You know rivers are remarkably resilient,” Butler says. “They can handle a normal amount of mud.”

But he says the amount of mud in the Cahaba is not normal. Walking along a section of the river in Hoover, Butler leans over and scoops up a handful of rocks.

“So if you see how much dirt there is in it,” he says, “there’s not a lot of space in between the rocks for bugs and mussels and snails to live.”

Butler says it is now more common to see large mounds of dirt and gravel that pile up in the middle of the river, the result of sediment pushed downstream. Over the years, he says parts of the river and its tributaries have accumulated as much as 20 feet of extra sediment.

That makes it impossible for some aquatic life to survive, according to Randy Haddock, field director of the Cahaba River Society.

“Here is a list of some of the existing and some of the extirpated species that are federally listed as either threatened or endangered species on the Cahaba,” Haddock says, pointing to a list of about a dozen species. “All of them say it’s because of excessive sediment smothering their habitat.”

For example, Haddock says today’s population of mussels is about one-tenth of what it used to be. He says the animals naturally rest on a hard surface like rock, so large amounts of sediment increase their risk of sinking to the bottom of the river and filling with mud.

Beyond the loss of habitat and the decline in biodiversity, sediment increases the turbidity of water and can carry bacteria and metallic particles.

Haddock says the issue affects all residents of Birmingham, because the Cahaba is the city’s biggest source of drinking water and sediment is the biggest pollutant threatening that source.

“It’s a very different pollution problem,” he says, “in that you can’t point to a pipe with nasty stuff coming out of the pipe saying, ‘That’s poisonous, you need to limit how much of that comes out.’”

Haddock says most of the sediment in the Cahaba comes from erosion along the riverbank, caused by increasing volumes of stormwater runoff. The issue largely stems from development upstream, and the impact can be seen over decades.

Another more immediate problem happens during construction. When land is first disturbed, trees are cut down and bulldozers roll in, exposed dirt and gravel can wash into nearby streams. UAB engineering professor Wesley Zech says this is a problem across the U.S.

“Currently, research has shown there’s 80 million tons of sediment that is discharged into our nation’s water bodies from construction sites every year,” Zech says.

Developers and builders in Alabama are required to prevent this via permits issued by local governments and the Alabama Department of Environmental Management (ADEM).

But activists like Randy Haddock say there is not enough oversight and enforcement of these regulations.

“To actually levy a fine against somebody for allowing sediment to come off their construction site is a byzantine process,” Haddock says.

In 2018, ADEM issued 23 penalties statewide against builders for land disturbance violations like failing to control sediment. Haddock and Cahaba Riverkeeper David Butler say that number represents a fraction of actual violations.

On the other hand, construction workers say it can be difficult to keep all the dirt contained on a site, especially in Alabama where the land can be hilly and it rains a lot.

This was part of the discussion at a recent workshop in Pelham, where site planners and designers learned the latest research on sediment and erosion control. They reviewed which fabric is best for a silt fence and when to use other barriers. Workshop attendee Phillip Voss, division permit manager with a Texas-based construction company, says when trying to control sediment, every site presents different challenges.

“One thing that we promote right now is ‘be the water, think about where the water’s going.’” Voss says. “Because not only are you trying to manage that water, but you’ve got to manage the quality of that water.”

Engineering professor Wesley Zech says these controls aren’t new.

“They’ve been used for quite a long time,” he says. “But now we see it’s becoming more of a priority.”

Zech says that’s because the impacts of sediment pollution are becoming more evident.

A few years ago, a state environmental study recommended reducing the amount of annual sediment loading in the Cahaba by around 50%. Construction is just the beginning. Experts say to really see progress, developers have to change not only how they build, but how they design, from the ground up.

Editor’s Note: The Cahaba River Society is a member sponsor of WBHM, but our business and news departments operate separately.

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.

Oil price surges as Iran steps up attacks on ships in the Persian Gulf

Markets seesawed on Day 13 of the war in the Middle East, as two oil tankers were struck by projectiles near Iraq's southern ports and attacks between Israel and Hezbollah intensified.

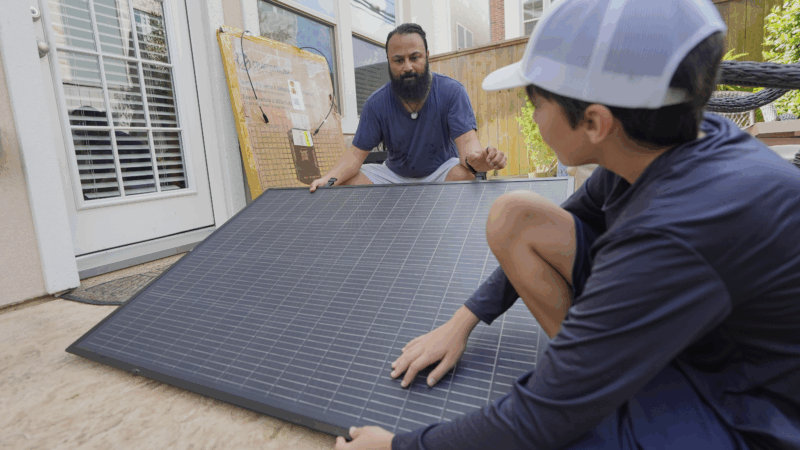

Easy-to-use solar panels are coming, but utilities are trying to delay them

Utilities are convincing lawmakers around the U.S. to delay bills that would allow people to buy solar panels, plug them into an outlet and begin generating electricity.

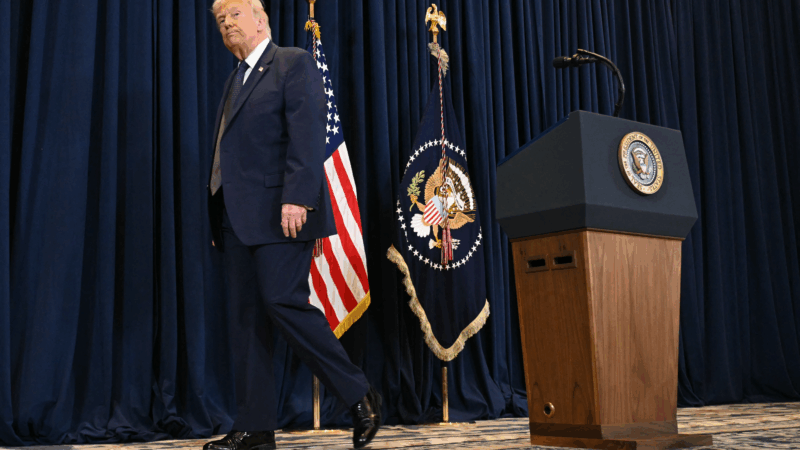

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.