Former Lawmaker’s Message Led to Concerns About Property Values

Former State Rep. Oliver Robinson abruptly resigned his legislative seat last November. Recently he confirmed to WBHM that he is under investigation, following an Alabama Media Group report. The details of that investigation aren’t known, but reports suggest it’s tied to his interference with efforts by the Environmental Protection Agency to test for contamination in his former district.

The stretch of quarries, rail lines, and smokestacks on the north side of Tarrant and Inglenook is where hundreds make their living, producing coke and other industrial goods.

But environmental groups say these factories emit toxins, polluting the air and the soil in communities around Hwy 79. Former State Rep. Robinson told residents that if the EPA were to declare their neighborhoods a Superfund site, property values would go down and that a cleanup could take at least 15 years.

Carolyn Cauthen, president of the Inglenook Neighborhood Association, says Robinson’s daughter spoke at one of their meetings, and lots of residents had concerns.

“What we were told and what was stated was that if the EPA come in and test your soil, then it would probably be hard to get loans or anything because it would make your property value go down,” Cauthen says.

It may hurt property values, but here’s the issue: a high-profile law firm, Balch & Bingham, paid Robinson $135,000 through a foundation in part to communicate with residents on the issue. That firm represents ABC Coke, a company environmental groups say is responsible for pollution in the area.

Robinson’s non-profit launched a campaign in 2015 that blanketed the community with pamphlets and signs. Robinson told residents that if they consented to EPA testing, they should demand another company test the soil at the same time to independently confirm results. Recent attempts to reach Robinson for comment were unsuccessful.

Michael Hansen, executive director of the environmental watchdog group GASP, says more residents would have allowed their soil to be tested had it not been for Robinson’s campaign.

“That was their goal to make people doubtful and fearful and question the EPA’s motives,” Hansen says.

He says residents have a right to know their environment is safe.

That’s especially true “in historically disenfranchised communities like the low-income areas of North Birmingham, Tarrant, and Inglenook that are primarily African American communities,” Hansen says.

A 2016 EPA report said contamination levels in Tarrant and Inglenook showed no need for EPA intervention.

Arthur Blackwell, a retiree who lives in Tarrant, had his soil tested by the EPA and says results showed no contamination. He says the air there is better than what it used to be.

“Every once in a while I’ll get a foul smell,” he says, “but hell, I get that from the septic tank systems from any of the other places. But it’s nothing that’s detrimental to my health.”

The Jefferson County Department of Health monitors air emissions and says there are no current violations with industries around Tarrant and Inglenook. But environmental activists question whether the small amount of testing that has been done is enough to give a true picture.

In Berlin, there are movies, there’s politics and there’s talk about it all

Buzz around whether the city's film festival would take a stance on the war in Gaza has dominated conversation in recent days.

Alex Ferreira wins 10th gold medal for Team USA, matching America’s highest total in Winter Olympics

Freeskier Alex Ferreira clinches a tenth gold medal for the U.S. in these Games, tying the U.S.'s all-time record for gold medals in a Winter Olympics.

Trump calls SCOTUS tariffs decision ‘deeply disappointing’ and lays out path forward

President Trump claimed the justices opposing his position were acting because of partisanship, though three of those ruling against his tariffs were appointed by Republican presidents.

The U.S. men’s hockey team to face Slovakia for a spot in an Olympic gold medal match

After an overtime nailbiter in the quarterfinals, the Americans return to the ice Friday in Milan to face the upstart Slovakia for a chance to play Canada in Sunday's Olympic gold medal game.

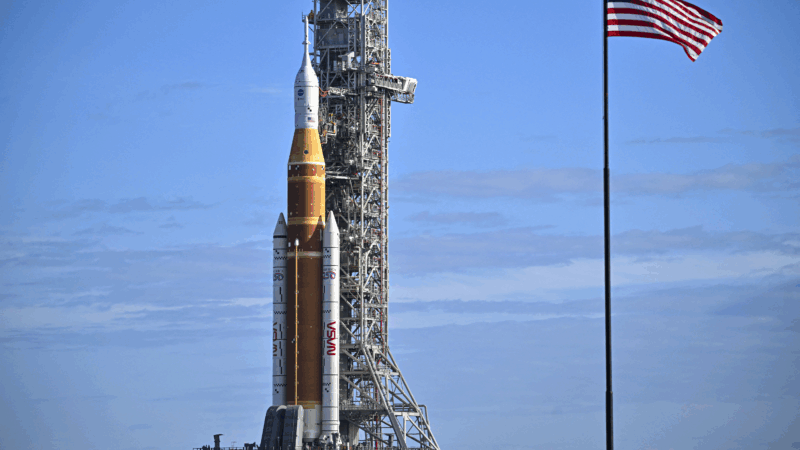

NASA eyes March 6 to launch 4 astronauts to the moon on Artemis II mission

The four astronauts heading to the moon for the lunar fly-by are the first humans to venture there since 1972. The ten-day mission will travel more than 600,000 miles.

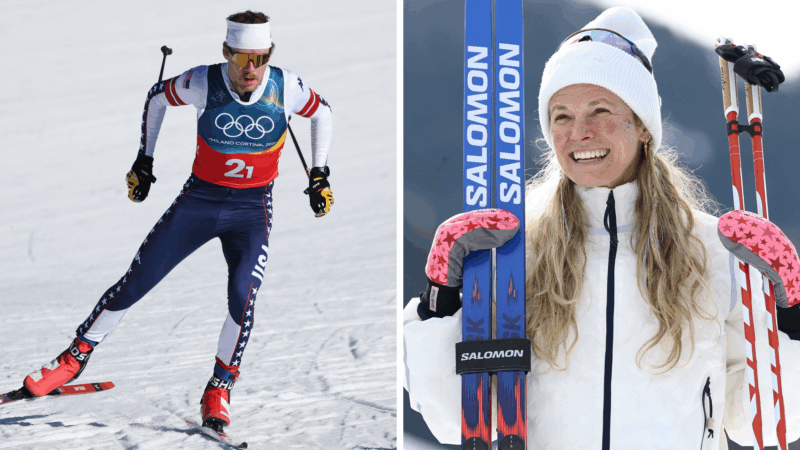

Skis? Check. Poles? Check. Knitting needles? Naturally

A number of Olympic athletes have turned to knitting during the heat of the Games, including Ben Ogden, who this week became the most decorated American male Olympic cross-country skier.