Fentanyl is killing more young people in Alabama

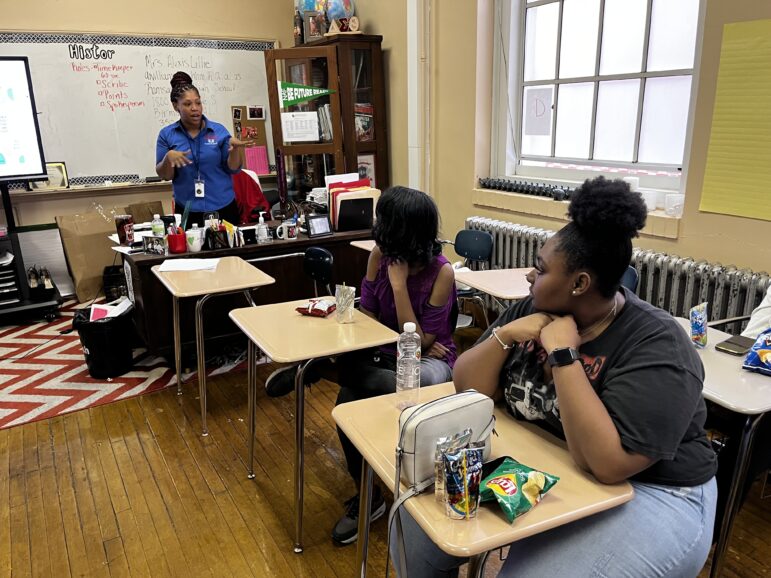

Students in InFOCUS at Ramsay High School have candid discussions about drugs, mental health and their school community. It's club sponsored by the Addiction Prevention Coalition in multiple schools.

A few weeks after turning 18, Sebastian Brock died in September 2022 from an accidental fentanyl overdose. He’d gotten a counterfeit pill laced with the highly potent opioid and that was it. His family got the call on the way back to their hometown in North Alabama after dropping their daughter off for college.

“It was indescribable. It was the worst thing you could imagine for a parent,” said Michael Brock, Sebastian’s dad.

As a way to process the loss, Brock turned to social media.

“I found it very therapeutic. But what I also found was that it touched a lot of people,” he said.

For a month after Sebastian’s death, every day, on Facebook he shared his thoughts and feelings with his community.

“So, what would you do if a stranger came to town and murdered four or five of our youth? Well, that’s what has happened. That stranger is fentanyl,” he wrote in the Facebook post.

Brock said they didn’t have any “warning signs” with Sebastian. He was a good kid who got good grades and was a good friend. He and his son bonded over music, both skilled musicians.

“Sebastian was one of the most musically gifted teenagers I have ever seen in my life. My son could play anything. You give him an instrument he had never played before, and in 5 minutes he would do something with it,” Brock said.

Brock said he and his wife knew fentanyl was dangerous, but he didn’t know just how dangerous and wants parents to be aware that this kind of tragedy could happen to their family too.

“I grew up in the eighties. Those days are gone,” he said. “This is not the seventies. It’s not the eighties. It’s not the nineties. And the days of casual drug experimentation for teenagers are over. It’s simply over.”

Youth are at risk

Data from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration found 60% of fake prescription pills are laced with a lethal dose of fentanyl and recently, it’s been showing up in marijuana.

“There still is a lack of awareness in the community about the products that fentanyl is contaminating,” said Darlene Traffanstedt, medical director at the Jefferson County Department of Health. “I think for a long time we’ve thought youth is not at risk. But because of the counterfeit pills that are in our community and because of the marijuana contamination, now that does absolutely impact youth.”

Traffanstedt said most young opioid overdoses are accidental, because they weren’t looking for it. Fentanyl is tasteless, colorless and odorless and most teens experimenting with drugs haven’t built up an opioid tolerance, meaning a drug laced with a minuscule amount of fentanyl could be fatal.

“Our overall average age is actually shifting down for both fatal and non-fatal overdoses,” Traffanstedt said, “It has historically been around 40 years of age … now it has shifted down to 37-ish. So that means that we’re seeing younger individuals and that is driving that average age down.”

Over the last couple of months, that data has lead to more targeted campaigns about opioids towards middle and high schoolers, which the department has never had to do before.

They’re hosting parent town halls in schools and distributing Narcan, a drug that can reverse an opioid overdose, to every public school system in Jefferson County. Narcan and fentanyl test strips are also free to all Jefferson County residents regardless of age.

“We want them to be prepared,” Traffanstedt said. “If it’s just one student, we want them to be prepared to respond to that one student.”

She said the first message to students is always to not do drugs but it’s also important for people to know how to reduce the risks.

Talk to students

Taritha Bracy, a teacher at George W. Carver High School, sees early intervention as the best defense against student drug abuse. The health teacher of 28 years said she’s seen teens making more and more dangerous decisions, but it’s not widely acknowledged.

“It’s kind of like hush hush, just a slip on the road,” Bracy said. “But it’s happening everywhere. You know, you hear situations. You know, kids are just falling out.”

In her classes, Bracy tries her best to educate students but said she takes advantage of outside resources, like the Addiction Prevention Coalition — a nonprofit spreading awareness about drug abuse. Bracy is the faculty advisor for Carver’s InFOCUS chapter, a club hosted by the APC in multiple Birmingham-area schools that gives students the opportunity to have open conversations about drugs generally and these days specifically fentanyl.

The group tries to reach students where they’re at.

“DARE was used a lot in the 1970s and ‘80s during the war on drugs, and it wasn’t really effective,” said RavenJohnson, director of student initiatives with APC. “We try to provide factual information and be non-biased and don’t use fear tactics, because those don’t work for students, and then empower them to make the healthy decisions.”

Johnson said when educating kids about drugs there’s a fine line between looking like they are glamourizing drugs and informing teens about their effects. But she said kids need to understand nuance and how drugs affect their mind, body and community.

“Substance use impacts an entire community from so many different directions. So it has to deal with poverty, education, social, emotional learning,” Johnson said. ”So it really takes a lot of partners and us to work together to get it from all angles and make a difference.”

But Johnson also knows that having knowledge doesn’t always equal good decision making with adolescents.

“When you get in high school, it’s a lot of encouraging teens to talk to each other because once they get that age, they’re not listening to adults as much. [It’s] more impactful by hearing it from a best friend,” she said.

Students care

At the Ramsay High School InFOCUS chapter, students meet once a month after school to have candid discussions about drugs, mental health and their school community. It’s a small group of students but they get the conversation started about opioids and illicit drugs.

During a recent meeting, when asked if they knew someone who did drugs or died by drugs, all the students at the meeting nodded but were hesitant to share. But one student got the courage, Ste’Phan Lawson.

“I had a friend, he passed like last year from an overdose. We used to like hoop and all that. There were 12 of us. And of the 12 of us on the team, I think four of them died and two from overdoses,” Ste’Phan told his peers.

The students then talked about how music, social media and peer pressure influence them. They said they like having these conversations with friends and trusted adults in school. They’re thinking about inviting parents to a meeting to further the conversation. Student Kaylan Mobley thinks getting parents to listen might be hard, but wants to make it happen.

“They think as long as you got a roof over your head and clothes on your back and food to eat daily, that you’re okay,” Kaylan said. “But a lot of kids, mentally, they’re not okay. And they go through stuff and a lot of parents don’t want to hear it. So that can lead to drug abuse. So I think that conversation can be had as long as they have an open mind and are willing to listen.”

Kaylan said there are always people in school who will act like they don’t care about the dangers of drug use, but she says the majority of her peers do care and they want the community to know that.

Kyra Miles is a Report for America corps member covering education for WBHM.

Bikes and bakeries are back: War-torn Khartoum struggles to rebuild

Government forces retook the capital city from rebel troops in April. Now comes the task of rebuilding what was once a bustling metropolis on the Nile.

As the WNBA season tips off, here are 4 of our biggest questions

Will a new-look Indiana Fever contend in Caitlin Clark's second year? Will A'ja Wilson win a record 4th MVP? And the biggest question of all: Can the league as a whole build on last season's success?

Scientists have figured out why flamingos are such weird eaters

Flamingos look silly when they eat, but new research suggests they're actually being smart.

Trump denounces ‘activist’ judges. He’s not the first president to do so

Criticism of "activist" judges predates the term and has come from both ends of the political spectrum. Democratic and Republican presidents alike have accused the courts of exceeding their constitutional role.

Two officials fired by Trump return to court to challenge his power

Cathy Harris and Gwynne Wilcox, Democratic board members of independent agencies, argue President Trump lacked the authority to fire them, citing federal law and Supreme Court precedent.

Why UnitedHealth’s terrible year is dragging down the Dow

The health care giant's shares are down more than 50% in the last month. That's hurting the powerful U.S. stock-market index.