Trade wars grew America’s auto industry. Historians warn today’s tariffs won’t

A Hyundai assembly plant in Montgomery, Alabama, employs about 4,200 workers, according to the South Korean car company. July 11, 2024.

Economists like to say no one wins a trade war. The counterpoint to that claim is the American automobile industry.

Americans’ love of their home-built pickup trucks came from a dispute over chicken exports in the 1960s. Ronald Reagan’s hardball negotiations with Japanese automakers in the ‘80s brought their factories stateside. Just the whiff of tariffs in the ‘90s helped create another wave of foreign car companies setting up in the South.

But while President Donald Trump revists the trade war playbook with 25% tariffs on auto imports, industry historians say this might be the one time to bet against history repeating itself.

The American auto industry looks much different today, due in large part to those past trade victories. Back then, the U.S. had little to lose cutting off international ties. Now, the distinction between American or foreign cars isn’t much more than semantics, as overseas buyers purchase cars with a German label and built with American hands.

Essentially, America’s car making business has more to lose today and less to gain.

“The context is completely changed,” said A.J. Jacobs, an auto historian and professor at East Carolina University. “Applying 1970s policies to the 2020s is not practical.”

Japanese automakers voluntold to build in America

American’s love big cars — at least until gas prices go up.

That was certainly the case at the end of the ‘70s, when oil prices shot up about a dozen times higher than it was at the decade’s start due to an energy crisis. Consumers flocked away from gas guzzling American models and turned to fuel-efficient Japanese cars from companies like Toyota, which was shipping its cars from overseas.

“They’re not pretty. They are not fast. They’re not going to get you a girlfriend,” Jacobs said. “But they’re going to get you to work. And they’re not going to make you broke.”

This led to the Big Three of American car manufacturers — Ford, Chrysler and General Motors — begging the White House for help. In a deal with Japanese automakers, Reagan agreed to veto a tariff bill from Congress, according to Jacobs’ book “The New Domestic Automakers in the United States and Canada.” In exchange, the Japanese companies voluntarily put limits on the number of vehicles they would ship to America.

A little less than two years later, Toyota announced a joint venture with GM to reopen a Fremont, California, assembly plant to start making cars in the United States. Honda, Nissan, Mitsubishi and Subaru also built new American factories in the ‘80s.

Germans companies follow Japan to America

German automakers never faced a quota or the pressure that Japanese companies felt from the United States, but they still sweated the threat.

“They were aware of what happened with the Japanese makers,” John Mohr, an auto historian and assistant professor at the College of Southern Maryland, said. “There was fear that if they did not localize production that something else might disrupt that relationship.”

To protect their share of the American car market, a second wave of foreign investment happened in the ‘90s, particularly with those German automakers going to the South. BMW opened in South Carolina, 1994. Mercedes-Benz went to Alabama in 1997. Hyundai from South Korea followed in 2005 to Alabama.

Southern states’ anti-union attitudes and willingness to offer massive incentive packages soon turned the region into a manufacturing powerhouse for foreign car companies.

Diminishing returns due to past victories

Ironically, those past victories make a new auto trade war much more difficult for the U.S. to win now.

Alabama alone already has assembly plants from four major foreign automakers. Across the country, non-American companies are pumping out millions of vehicles each year. Jacobs doesn’t see much room for growth even with pressure from tariffs.

“The market is not going to go that much bigger,” Jacobs said. “How many more are you going to bleed from the stone?”

Companies like Mercedes-Benz produce so many cars in the U.S. that they’re being exported and sold in other countries. Auto exports, from cars to parts, shipped out of the U.S. were valued at $54 billion last year — more than five times what they were in 1970 after adjusting for inflation.

This trade supports American auto jobs — trade now threatened as Trump’s tariffs cause other countries to consider their own barriers.

“If we really do an international global trade war, it’s very likely those exports will be imperiled,” Mohr said. “And the people whose jobs rely on those may find themselves out of work.”

Tariffs alone won’t lead to an auto-job renaissance

When looking at the past, hyper fixating on tariffs as the sole reason for the U.S. foreign auto boom is shortsighted, Jacobs said.

Japanese companies started building cars in America not just because of tariffs, but because Americans wanted to buy Japanese cars. Today, China is the hot market companies want in on, Jacobs said, leaving the U.S. with far less leverage compared to the ‘70s.

That’s not to say foreign automakers are done expanding in the U.S. Hyundai announced last month it would invest $21 billion in America, including a nearly $6 billion steel mill in Louisiana — notably a deal that came together ahead of the auto tariff announcement.

But along with market demand, companies must consider the local workforce, the supply chain, transportation costs, currency exchange rates and a whole list of other factors that could render tariff pressure moot before they build a new factory or expand an old one.

Economists warn there’s another factor that means any manufacturing gains today will lead to a lot fewer jobs than they did decades ago — automation.

Over the last quarter century, the country has lost about 300,000 auto jobs, much of that disappearing due to automation. Any new factory coming to the U.S. will likely also be a state-of-the-art factory, meaning more robots and fewer workers — a problem tariffs can’t solve.

“There’s a big difference between the economics of the 1970s and the economics of now,” Ben Meadows, an economist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said. “And the 2,000 pound Sasquatch in the room that nobody is talking about is automation.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Four top U.S. speedskaters to watch at the Olympics

U.S. speed skaters set to compete in Milan are drawing comparisons to past greats like Eric Heiden, Bonnie Blair, and Apolo Ohno. Here are four to watch in the 2026 Winter Olympic Games.

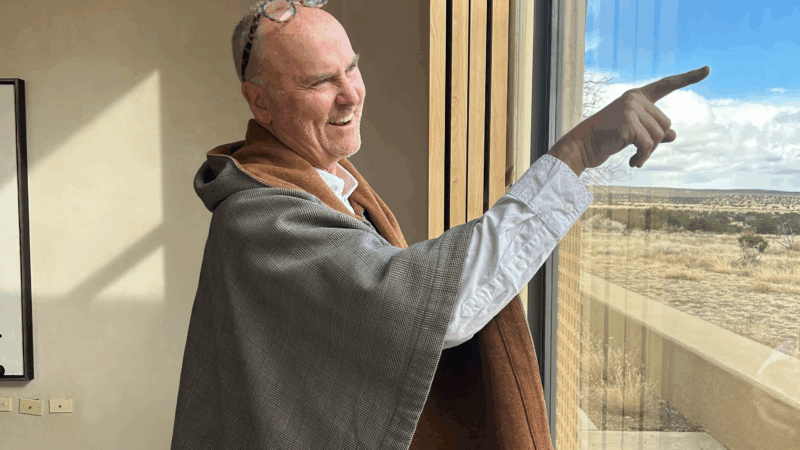

Need a new path in midlife? There’s a school for that and a quiz to kickstart it

Schools across the country are offering courses and retreats for people 50+ who want to reinvent themselves and embrace lifelong learning and discovery.

A ‘Shark Tank’ alum needed cash to pay tariffs. This shadowy lending world was ready

How about $350,000 within hours? The pitches flood small businesses: "No hidden fees, No BS." These financial lifelines are barely regulated and can turn into trip wires.

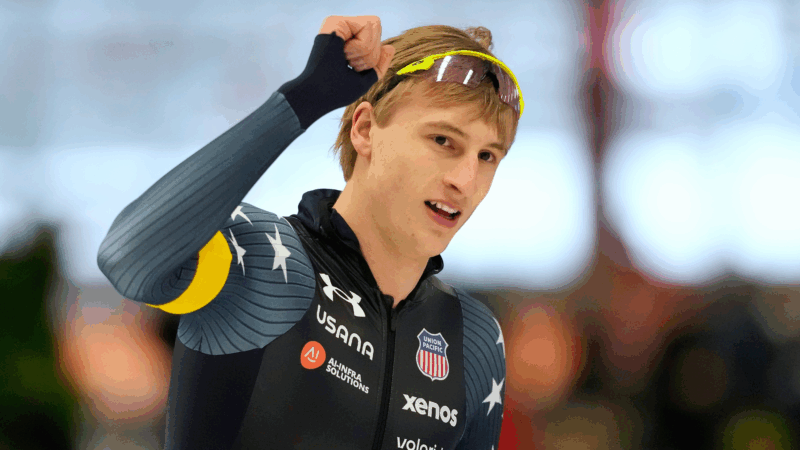

U.S. skater Connor McDermott-Mostowy joins record number of out LGBTQ Winter Olympians

When U.S. speedskater Connor McDermott-Mostowy makes his Winter Olympic debut in Milan, he'll join a record number of out LGBTQ athletes. But of the 46 out athletes, only 11 are men.

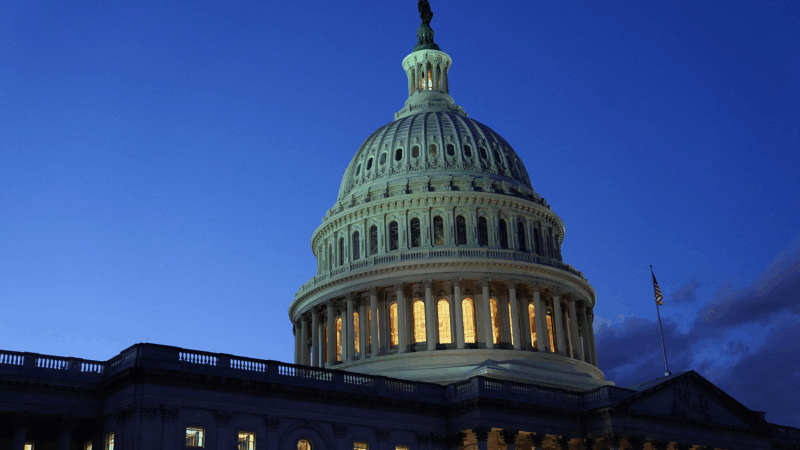

5 glaring warning signs for Republicans in this year’s midterm elections

Here's why Republicans are facing an uphill battle, particularly for retaining control of the House.

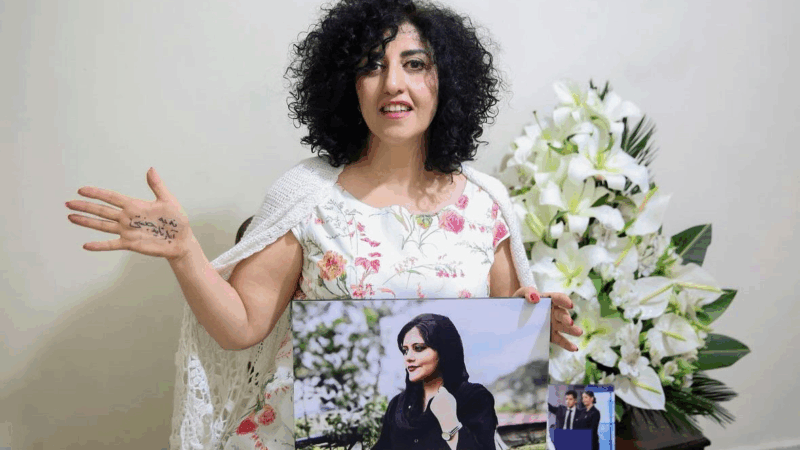

Crackdown on dissent after nationwide protests in Iran widens to ensnare reformist figures

Detained Nobel Peace Prize laureate Narges Mohammadi has received another prison sentence of over seven years.