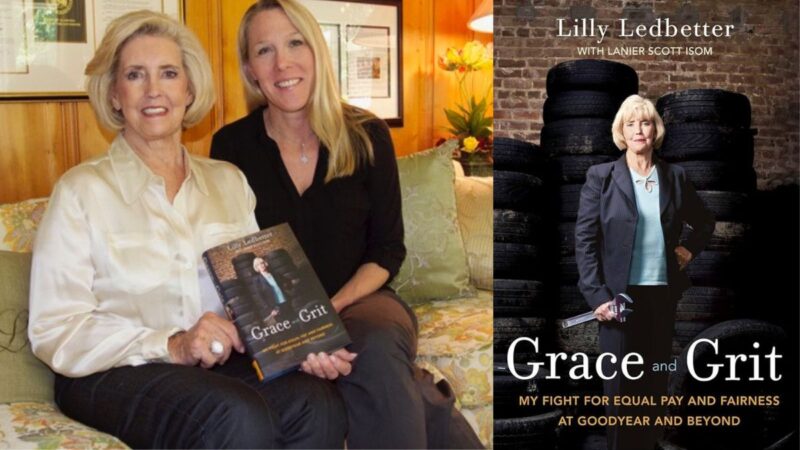

The story of Lilly Ledbetter’s fight for equal pay comes to the big screen

Lilly Ledbetter is an icon in the fight for equal pay. Ledbetter was a manager at the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. plant in Gadsden. Once she learned she was earning less than her male colleagues – she sued the plant. Ledbetter’s story is being turned into a movie, which comes out Friday.

Lanier Isom is a reporter from Birmingham who has covered Ledbetter extensively. Isom took the unofficial role as Ledbetter’s historian on the movie’s set. She sat down with WBHM’s Kelsey Shelton to explain why Ledbetter’s story needs to be told today.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Lanier, if you could please just tell us about Lilly’s story – introduce us to Lilly.

Lilly Ledbetter grew up in Possum Trot, Alabama, which is in North Alabama, a tiny town, and she grew up without any running water or electricity. She grew up picking cotton to earn extra money. At one point her clothes were sewn out of feed sacks, so she grew up in abject poverty and only had a high school education. But she was full of determination for a better life, and ambition.

And how did Lilly find her way at the Goodyear in Gadsden?

In 1979, she saw an ad in Businessweek for the new radial plant. And at the time she was working at H&R Block and she was like the manager over a huge area. She was really good with numbers and math. She saw the ad and they were hiring women and Backs in management for the very first time. This is 1979 in North Alabama. The Goodyear Plant, which is the way out for a better life for the majority of people in the community, the Goodyear plant always signified in Lilly’s growing up the families that got to go to the beach over spring break, that had the nice clothes. So she knew that there would be a good paycheck in management and her kids were about college age at that time. So, she wanted to do the right thing for her family. She always put her family first.

What was Lilly going through at the Goodyear?

You can’t even imagine the level and consistency of harassment that she experienced. It went from her supervisor telling her that she’d get a promotion if she went to the Ramada Inn with him, to her brakes being cut, to her windshield being also cut out, to tobacco juice all over her car, to being followed home at night. It was constant. So she faced real physical harm and danger from the men who did not want her there.

And then all that on top of being paid less than them.

Exactly. So she sues in 1999, and John Goldfarb is her attorney, and she wins in the Northern District Court over $3 million, but of course that’s reduced to $360,000, I think. Goodyear appeals, the circuit court rules against her saying she should have sued within 180 days of working at Goodyear when she started. And then she takes it all the way to the Supreme Court. And that’s when Ruth Bader Ginsburg stood up in her dissent and said, ‘Lilly, you have to change the law back to its original intent.’ And in 2009, President Obama signed into law the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Restoration Act.

You wrote one of the goals of reporting on Lilly was to answer the question, ‘Why Lilly?’ So what is it about her life and journey that you think makes her story one that needs to be told?

I think it needs to be told now more than ever because of the times we live in and the rollback of women’s rights and workers’ rights in the workplace. Lilly never ever gave up. Most women are underpaid. In fact, the pay gap is greater than it’s ever been in the past 20 years. Why Lilly, who has the law named after her, when the majority of us have been underpaid in the workplace. But Lilly just had this determination and she refused to accept defeat, so to speak. She had a lot of losses and she never saw a penny of anything. What she did was for the good of American families. And she used to always say, this is not a women’s issue. This is a family issue; this is important from Walmart to Wall Street. Lilly just had the grit.

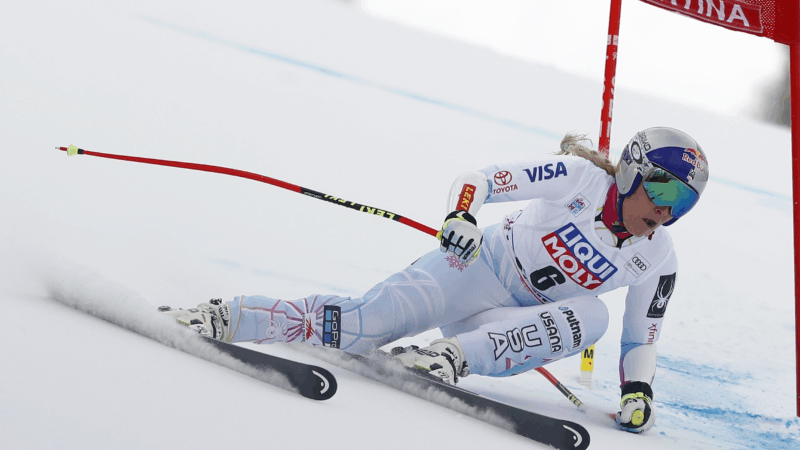

For many U.S. Olympic athletes, Italy feels like home turf

Many spent their careers training on the mountains they'll be competing on at the Winter Games. Lindsey Vonn wanted to stage a comeback on these slopes and Jessie Diggins won her first World Cup there.

Immigrant whose skull was broken in 8 places during ICE arrest says beating was unprovoked

Alberto Castañeda Mondragón was hospitalized with eight skull fractures and five life-threatening brain hemorrhages. Officers claimed he ran into a wall, but medical staff doubted that account.

Pentagon says it’s cutting ties with ‘woke’ Harvard, ending military training

Amid an ongoing standoff between Harvard and the White House, the Defense Department said it plans to cut ties with the Ivy League — ending military training, fellowships and certificate programs.

‘Washington Post’ CEO resigns after going AWOL during massive job cuts

Washington Post chief executive and publisher Will Lewis has resigned just days after the newspaper announced massive layoffs.

In this Icelandic drama, a couple quietly drifts apart

Icelandic director Hlynur Pálmason weaves scenes of quiet domestic life against the backdrop of an arresting landscape in his newest film.

After the Fall: How Olympic figure skaters soar after stumbling on the ice

Olympic figure skating is often seems to take athletes to the very edge of perfection, but even the greatest stumble and fall. How do they pull themselves together again on the biggest world stage? Toughness, poise and practice.