In the fight over Louisiana’s execution plans, religion plays a prominent role

A death penalty opponent protests the execution of Alan Miller by nitrogen gas in Atmore, Alabama, on Sept. 26, 2024. Miller was the second man Alabama executed through this method.

Louisiana’s recent push to resume executions has thrust religious opposition to the forefront, energizing a coalition of people from different faiths who oppose the state’s plan to carry out death sentences.

That loose coalition comprises advocates from Catholic, progressive Protestant and Jewish traditions, the latter of whom don’t universally oppose capital punishment, but decry Louisiana’s aim to execute people by nitrogen gas.

Work by the diverse group of faith advocates mirrors that seen among death penalty opponents elsewhere in the South, experts said. It also shows how this issue aligns an interfaith group who may not necessarily share views on other hot-button social topics, such as abortion.

There’s a history of religious engagement with social questions, especially about violence, crime and punishment, said Timothy Gutmann, an assistant professor of philosophy and religion at the University of Southern Mississippi. But he noted a curiosity about these arguments being put forth in the politically-conservative South.

“The South has always been the most religious region, and it’s probably the region that’s least persuaded by the faith-centered arguments in favor of civil rights and opposition to the death penalty,” he said.

Religious death penalty opponents in Louisiana are working in response to recent movement on executions, which had been dormant since 2010. But legislation last year led to an expansion of the state’s execution methods to include nitrogen gas and electrocution.

Louisiana cleared a path to resume executions via the gas method after difficulty obtaining the drugs used for lethal injections. Mississippi, Alabama and Oklahoma have also moved to legalize the gas method, but only Alabama has carried it out.

Earlier this month, Gov. Jeff Landry announced the state finalized an official protocol for the nitrogen gas method, which is controversial. That led to the signing of death warrants, including for an elderly man who died of illness. One execution by gas, of Jessie Hoffman, is set for March 18, though court challenges to that case are ongoing.

In response, religious leaders have rallied, penned editorials and called on supporters to mobilize via phone calls, social media videos and emails. Sister Helen Prejean, the noted death penalty opponent from Louisiana, said in a phone interview that faith leaders are joined by human rights activists in their opposition. She said that includes objection to the gas method as “so obviously terrible and cruel.”

Prejean was critical of officials trying to score “political points” by pushing for executions and to be seen as “tough on crime.” She said officials engage in “selective” interpretations of the Bible to justify their actions, but that those contradict the conclusions of the Catholic Church.

“Who are we to decide that life can be terminated, and that people are finished and can’t change?” Prejean said.

In one of the nation’s most “highly religious” states — where it is common for political leaders to profess their faith or say they are guided by it — faith activism also highlights differences between how officials draw upon their faith for their work in the public sphere.

For example, it draws a contrast between the relative Catholicisms of former Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards, who came out against the death penalty toward the end of his term, and of Republican Gov. Jeff Landry, who has led a push to resume executions.

Landry’s aides did not respond to multiple emailed interview requests for this story or specific questions, but he has said he views the carrying out of capital sentences as a “contract” between the state and the victims of crime.

“When we fail to abide by our promises and our contractual obligations to victims out there, how can we go around and say that we have any credibility on anything else that we do?” he said at a news conference in Thibodaux last year.

“States around us are finding ways and methods to execute those that have been tried and convicted and sentenced to death.”

‘Points of overlap’

One of the most visible and unique aspects of faith opposition thus far has been from the Jews Against Gassing Coalition.

On Feb. 17, the group of Jewish leaders and their supporters gathered on the steps of Touro Synagogue to speak out against the nitrogen gas execution method. A few described how entire branches of their family had been felled by the Nazis, including in gas chambers.

While some of their members do categorically oppose the death penalty, the group’s more general message is that gas executions evoke the trauma of the Holocaust, and are therefore unacceptable even for those members who do support capital punishment.

The public protest builds on lobbying which began in the state Legislature last year as nitrogen gas executions were legalized, said Naomi Yavneh Klos, one of Jews Against Gassing Coalition’s leaders. She said some lawmakers were unaware of Jewish perspective on this issue and welcomed it, while others were less receptive.

Yavneh Klos is also a professor at Loyola University New Orleans, which historically is a Jesuit college, and said she has heard from Catholics who are pleased about the prospect of an alliance on this issue.

“My Catholic colleagues are all very excited and supportive of our efforts, because it aligns with their efforts,” she said.

Marc Boswell, the pastor of St. Charles Ave. Baptist Church, said he attended the Jews Against Gassing Coalition event to support their cause. Their church has also hosted a lecture series against the death penalty, and Boswell has written publicly to oppose the execution plans.

For him, the nitrogen gas method is less important than a general objection to capital punishment. But he was not surprised by the interfaith alignment on this issue.

“Both Christian and Jewish, there are points of overlap in terms of our ethical positions toward the sanctity of life, and the inherent dignity that we believe that all human beings share,” he said.

Catholic initiatives include a note on a local dioceses’ website with instructions for supporters to write the governor to oppose executions. The bishops said in a recent statement that they were “saddened” by the move to issue death warrants.

“This only contributes to the culture of death,” they wrote. “We promote a culture of life, not death, in this great State we love. As bishops, we will continue to promote life from conception to natural death and work to end the execution of another human being.”

The Catholic view also includes the work of advocates like Prejean. In addition to religious arguments, she cites Louisiana’s legacy of slavery and research that shows people of color are more likely to face death sentences, especially when victims are white.

Hoffman, a Black man, was convicted in a case involving the rape and murder of a white woman, Mary “Molly” Elliott. He was tried in “an atmosphere of overt racism” in St. Tammany Parish court, attorneys for him wrote in a 2009 court filing.

Hoffman is a practicing Buddhist, other court documents show.

How faith informs political choices

Michael Altman, a professor in the department of religious studies at the University of Alabama, says he’s seen similar coalitions of faith-based death penalty opponents in his state, which led the nation in executions last year.

He said these advocates are working in red-state environments where a theology of “redemptive violence” runs under much criminal-justice policy — roughly, that notion that violence and death can have a higher purpose, linked to the story of Jesus’ crucifixion. But some religious branches, he said, interpret those same texts in a different way, with more attention to the idea of the sacredness of human life.

“There’s these sort of theologies that are competing on both sides, and it kind of depends where the emphasis lies,” Altman said.

Differing interpretations of religious teachings could help explain apparent contradictions in how state leaders are guided by their own faiths in public and political life, as seen in the case of the former and current Louisiana governor and their shared religion.

Former Gov. Edwards cited his faith as well as challenges with the expense of capital punishment and the repeated exonerations seen in Louisiana’s criminal justice system.

The death penalty is “wholly inconsistent with Louisiana’s pro-life values, as it quite literally, by definition, promotes a culture of death,” Edwards said in a 2023 address.

Edwards fielded inquiries from no less than the Vatican itself during an unsuccessful mass clemency push by people incarcerated on death row toward the end of his term, which Landry opposed.

Landry, meanwhile, has been insistent on the need for executions, dating back to his days as the state’s attorney general.

It is not clear if or how the governor’s Catholicism informs his thinking on this issue, despite indications that he draws on his faith for political decision-making. Recent public statements provide little information on this context and instead focus on more secular concerns.

“I took an oath to uphold the laws of Louisiana, and I will continue to fight for Justice for the victims,” he wrote on Twitter on Feb. 21.

In 2019, Landry also cast doubt on how “liberals” embrace religion for these arguments, telling a reporter for The Advocate newspaper that “when it comes to the death penalty, all of the sudden they all find God.”

It is not the first time Landry’s political life has been at odds with Church perspectives, such as a dust-up last year over funding for a Catholic Charities shelter over immigration issues. That drew a rebuke from a member of church leadership on a local news channel.

A message left with clergy at Landry’s childhood parish, St. Martin de Tours Catholic Church in Saint Martinville, seeking insight on how the governor may have formed his religious thinking on the death penalty, was not immediately returned.

Nationally informed

National death penalty opponents say they are watching faith-based organizing in Louisiana with some interest.

Cantor Michael Zoosman, founder of L’Chaim! Jews Against The Death Penalty, said he is aware of the work of Jews Against Gassing Coalition and called it an “inspiration to us all.”

Zoosman said he had cultivated pen pal relationships with all four men in Alabama who were then executed using the new nitrogen gas method. Seeing it take hold is symbolically “terrifying” for Jewish people.

Yavneh Klos, of the local Jewish coalition, said their work is important as reports of anti-Semitism are on the rise, and as lawmakers have professed their support for the Jewish community. The group believes there are no Jewish lawmakers in the statehouse.

She said their advocacy falls in line with a Jewish social justice tradition of tikkun olam, or healing the world.

Discussions of the death penalty in Louisiana, and faith-based objections to it, come as other Southern states including Arkansas move to potentially legalize nitrogen gas executions. That has also spurred opposition including from faith leaders.

The Rev. Dr. Jeff Hood — a Catholic priest and death penalty opponent who was an eyewitness to the nation’s first known nitrogen gas execution — gave a Zoom news conference to voice his concerns about the proposed legislation there last week.

In remarks to reporters, he described in graphic detail the execution of Alabama’s Kenny Smith, whom he said turned red, thrashed and filled a mask with bodily fluids for several minutes before dying.

Hood said the method is the antithesis of “pro-life” values.”

“You can’t talk about how much you love Jesus and how much you love suffocating people at the same time,” he said. “Even saying it right now, it’s unbelievable that I’m even having to talk about this.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

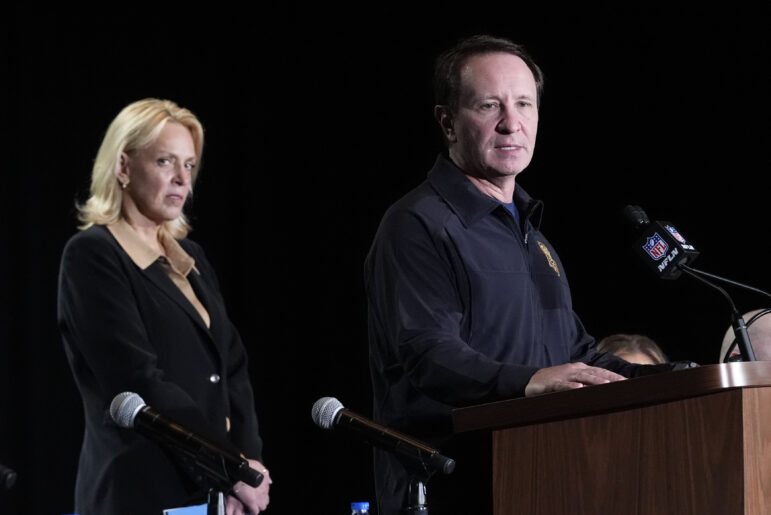

Federal judge acknowledges ‘abusive workplace’ in court order

The order did not identify the judge in question but two sources familiar with the process told NPR it is U.S. District Judge Lydia Kay Griggsby, a Biden appointee.

Top 5 takeaways from the House immigration oversight hearing

The hearing underscored how deeply divided Republicans and Democrats remain on top-level changes to immigration enforcement in the wake of the shootings of two U.S. citizens.

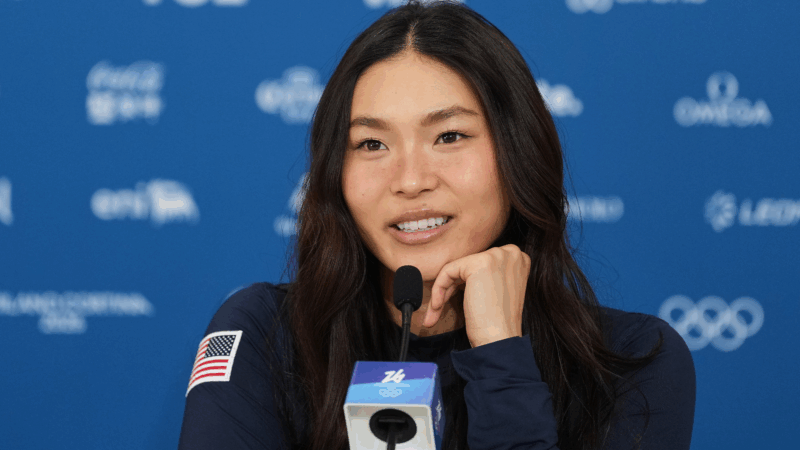

Snowboarder Chloe Kim is chasing an Olympic gold three-peat with a torn labrum

At 25, Chloe Kim could become the first halfpipe snowboarder to win three consecutive Olympic golds.

Pakistan-Afghanistan border closures paralyze trade along a key route

Trucks have been stuck at the closed border since October. Both countries are facing economic losses with no end in sight. The Taliban also banned all Pakistani pharmaceutical imports to Afghanistan.

Malinowski concedes to Mejia in Democratic House special primary in New Jersey

With the race still too close to call, former congressman Tom Malinowski conceded to challenger Analilia Mejia in a Democratic primary to replace the seat vacated by New Jersey Gov. Mikie Sherrill.

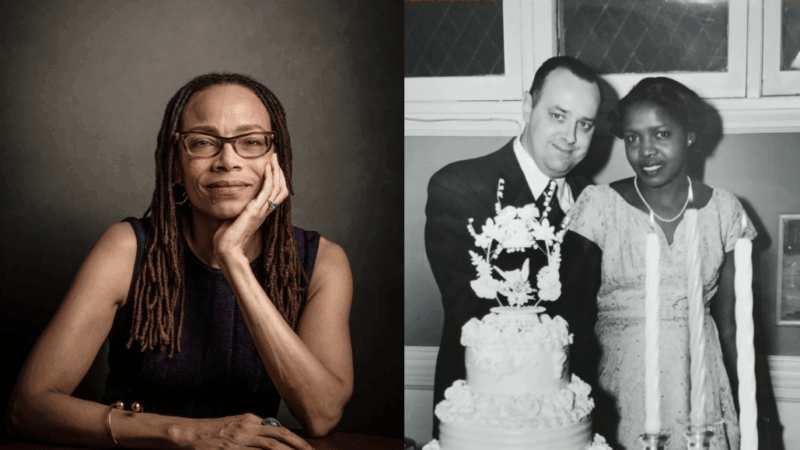

A daughter reexamines her own family story in ‘The Mixed Marriage Project’

Dorothy Roberts' parents, a white anthropologist and a Black woman from Jamaica, spent years interviewing interracial couples in Chicago. Her memoir draws from their records.