In New Orleans, focus shifts toward community recovery, healing after terror attack

Handwritten messages of support and remembrance decorate the wall of a building near the intersection of Bourbon and Canal streets in New Orleans on Saturday, Jan. 4, 2025. The makeshift memorial was created in honor of the 14 killed and 35 injured in the New Year's Day terror attack on Bourbon Street.

Tyler Burt knows the streets of the French Quarter like the back of his hand. A graduate student at Loyola University by day and a pedicab driver by night, the California native moved to New Orleans just over a year and a half ago.

New Year’s Eve had been a long day for Tyler. He started his shift at 10 a.m. and worked through the revelry of the night, aiming to finish by 3:30 a.m.

His last fare was a short ride — a young woman and her sister, whose parents had flagged him down on Bienville Street. The woman, tired and nursing aching feet after a night of walking through the French Quarter, needed a quick lift. Tyler took them just three blocks back to the start of Bourbon, near Canal Street.

Bourbon Street, a neon-lit artery of nightlife, was partially barricaded that night. The hydraulic bollards intended to block off the street weren’t functional, so police parked a cruiser as a barricade.

Tyler had just completed his transaction at 3:16 a.m. when a white Ford pickup truck sped around the police barricade. The father of his passenger, who moments earlier had shared a high-five with Tyler, was struck by the vehicle.

“He was run over while I was still in contact with him,” Tyler said. “I just remember him going under the vehicle. I think I even reached for him.”

But this was no accident. The FBI says the driver of the truck, Texas resident and Army veteran Shamsud-Din Jabbar, intentionally drove his truck around barricades and onto the sidewalk as a premeditated “act of terror.”

He acted alone, aiming to do as much damage as possible, killing 14 and injuring 35 before crashing the truck and getting into a shootout with responding police. He shot two officers before being shot and killed by police — ending the rampage.

As the carnage ensued, Tyler turned to see bodies flying into the air as the truck plowed down the crowded street. He grabbed a shaken coworker and moved them to safety. Police swarmed the scene, sirens overwhelming the chaos.

“At that point, I was just trying to take care of my friend,” he said.

‘Where do I begin supporting people?’

Burt’s passengers survived, and he’s been checking in with them as they recover.

Like many others who were injured in the attack, they were taken to University Medical Center, a state-designated trauma center in the city’s Tulane-Gravier neighborhood. The hospital was also where families of victims and other survivors gathered to look for their loved ones who were missing after the attack.

Dr. Erika Rajo, the Seeds of NOLA Trauma Recovery Center director at UMC, said she was nearly overwhelmed as she got to work early on New Year’s Day.

“I just had a moment of like, where to start? Where do I begin supporting people? There were just so many people,” Rajo said.

She met with many of the families, connecting them with mental health and financial resources, offering them emotional support and sometimes a shoulder to cry on. She also offered small things in the moment, like water, tissues or a blanket while they waited for more information.

“It was difficult because I didn’t have answers for them,” Rajo said. “But what I did have, I was able to validate what they were experiencing and just hold their emotions.”

The FBI has set up offices to help survivors and families of victims with financial support and mental health resources as the focus shifts toward recovery for the injured and the community.

Because many of those affected were visitors to New Orleans, Rajo and her team at University Medical Center are also connecting them with support organizations back home.

Healing takes time, and resources

The emotional toll of that night has been immense. Rajo said everyone in the community also felt the attack’s impact, including herself. She was born and raised in New Orleans and teared up when reflecting on how she felt in those moments.

“It’s just so sad to me because I love things like Mardi Gras and Jazz Fest and all these big crowded events,” she said. “And now to have this looming thing, it just feels really sad.”

A little more than 24 hours after the attack, Tyler described feeling disconnected from his own body, as though he were “astral projecting.” The memories of high-fiving the father, followed by the horrific impact, haunt him.

“It’s the worst thing I’ve ever seen,” he admitted. “There’s something insidious about someone doing bad things intentionally. I saw it clear a path through the crowd for two blocks.”

Rajo said it’s critically important to make sure everyone affected by the attack is connected to resources and support like the counseling services and financial assistance being offered by the FBI, nonprofits and others. Life doesn’t stop because you experienced trauma, she said.

“There’s all these things — bills and rent and just the practical things,” she said. “Those keep going and then other new stressors keep coming.”

Experts say people who experience trauma need this kind of help beyond a few weeks. It can be months, even years after mass casualty events like the New Orleans attack for people to recover, Dr. Robin Gurwitch, a professor and psychologist at Duke University Medical Center who studies disaster and mass violence, said.

“There’s not a timeline that says, if I’m grieving, this is when I should be doing better. It will have its ups and downs forever,” Gurwitch, who’s worked with survivors of events like the Oklahoma City bombing and Hurricane Katrina, said.

Support can come from many places, like trusted friends and family members, community resources and faith and cultural communities.

“There’s not a single, one-point where we get that support,” Gurwitch said. “But it is absolutely critical that we do.”

’There’s still so much good to hold on to’

Despite the trauma, Tyler is determined not to let fear take root.

“This wasn’t a homegrown issue. It’s not because of New Orleans,” he said. “I don’t think evil lives here. There’s a bigger problem in the world, and I’d rather meet it with love.”

For now, he’s leaning on the love and support of his community. A fund has been set up to allow him and his coworkers to take time off. Family and friends have rallied around him, refusing to let him face this alone.

“It’s remarkable, the love I’ve felt from people,” Tyler says, his voice soft but resolute. “In a world where so much can go wrong, there’s still so much good to hold on to.

For resources available in New Orleans, contact Crime Survivors NOLA here. For resources available from the federal government, contact the FBI here.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

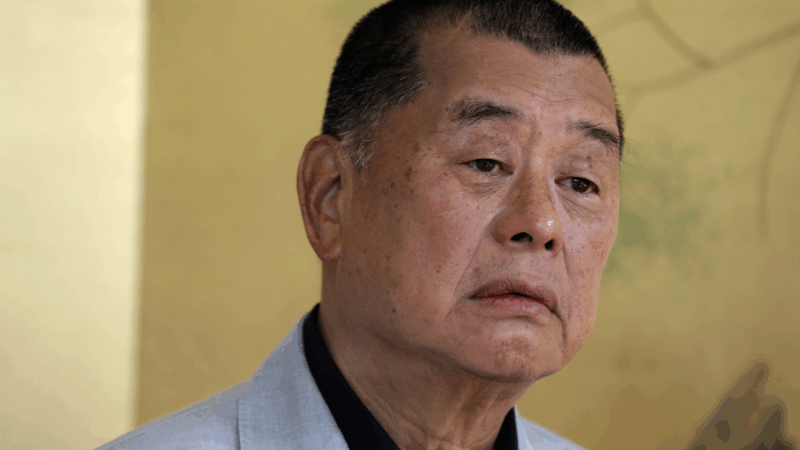

China critic and former media tycoon Jimmy Lai is sentenced to 20 years in a Hong Kong security case

Jimmy Lai, the pro-democracy former Hong Kong media tycoon and a fierce critic of Beijing, was sentenced on Monday to 20 years in prison in the longest punishment given so far under a China-imposed national security law that has virtually silenced the city's dissent.

China critic and former media tycoon Jimmy Lai is sentenced to 20 years in a Hong Kong security case

Jimmy Lai, the pro-democracy former Hong Kong media tycoon and a fierce critic of Beijing, was sentenced on Monday to 20 years in prison in the longest punishment given so far under a China-imposed national security law that has virtually silenced the city's dissent.

Center-left Socialist candidate wins over populist in Portugal’s presidential runoff

Center-left Socialist candidate António José Seguro recorded a thumping victory over hard-right populist André Ventura in Portugal's runoff presidential election Sunday, according to official results.

Seahawks win Super Bowl title, pounding the Patriots 29-13

Seattle's "Dark Side" defense helped Sam Darnold become the first quarterback in the 2018 draft class to win a Super Bowl, to win the franchise's second title.

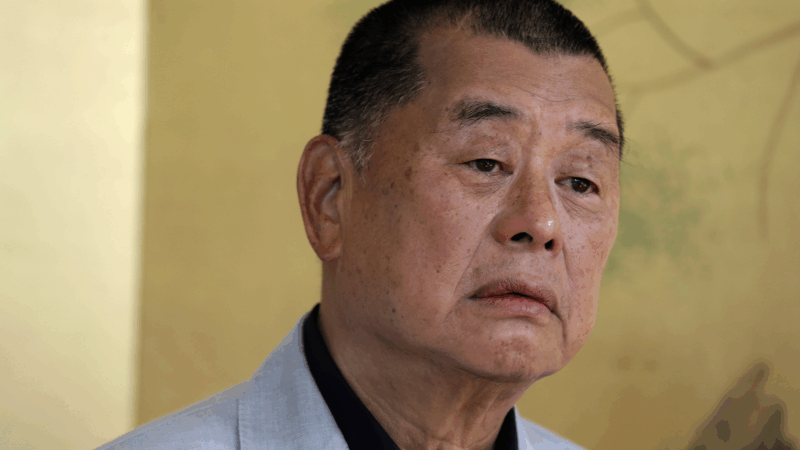

No, that wasn’t Liam Conejo Ramos in Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show

A publicist for Bad Bunny confirmed to NPR that the little boy in a blue bunny hat detained by ICE in Minneapolis last month did not participate in the Super Bowl halftime show.

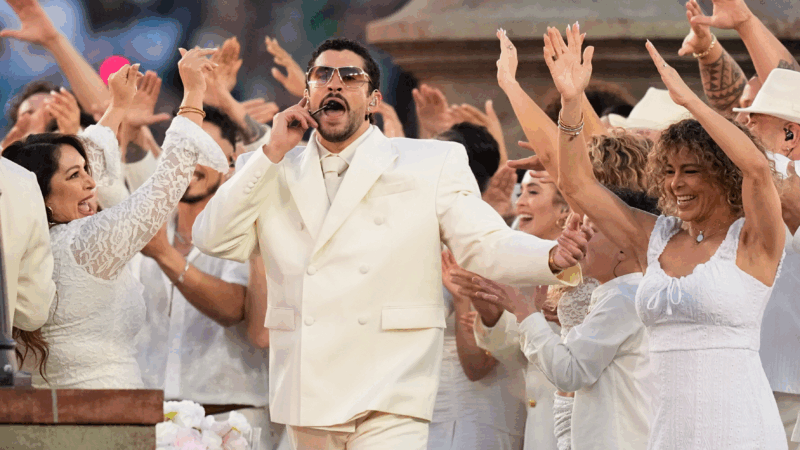

March for Life attendees may have been exposed to measles, DC Health warns

D.C. health officials are contacting people possibly exposed to measles at the March for Life in January, as confirmed cases rise nationwide.