‘Down but not out’: The punk zine that helped keep New Orleans’ culture afloat after Katrina

Antigravity editor-in-chief Dan Fox delivers and arranges the July issue of the magazine at a coffee shop in New Orleans on Tuesday, July 1, 2025. Fox says he believes in being a “good steward” and takes time to organize and clean up the media spaces at the magazine’s local distribution points, like music venues, libraries and cafes.

Editor’s Note: The Gulf States Newsroom’s Drew Hawkins contributes to Antigravity as a freelancer. This story was written and edited independently of anyone at Antigravity.

“I will say this: the power of the press is large and far-reaching.”

Leo McGovern documented his experience of Hurricane Katrina on an online blog he made for his small, punk-rock monthly magazine, Antigravity, writing about everything from evacuating at the last minute to using handmade press passes to get back into the city after the storm, showing them to state troopers blocking the roads.

To his surprise, it worked.

“And off we went into a part of the city that’s not supposed to be open for weeks,” McGovern wrote.

McGovern started Antigravity in June 2004, just over a year before he’d find himself sweet-talking his way back into a hurricane-ravaged New Orleans. The magazine remains in operation today, focusing on hyper-local stories and artists — in-depth features, interviews and schedules for local music venues — as well as comics and regular columns ranging from legal rights to gardening tips.

In the days before the storm, McGovern’s focus was on the deadline to get the September issue to the printer. It was set to be the first since the magazine started that might finally turn a profit.

In the last week of August, someone asked if he’d heard about a hurricane that was about to hit Florida and was then expected to head up the East Coast. McGovern said he wasn’t worried about it.

“And then came the weekend,” he wrote in his blog, “and with it the possibility New Orleans would be no more, and that at least the city would never be the same.”

Hurricane Katrina crossed over Florida into the warm waters of the Gulf, where it strengthened into a Category 5 before weakening to a Category 3 as it made landfall on August 29, 2005, devastating the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

After the city’s levee system failed, 80% of New Orleans was flooded — including McGovern’s and most of Antigravity’s staff’s homes. But through it all, McGovern knew he would come back and continue publishing the magazine.

Since 2005, thousands of local publications across the country have closed. That, along with more polarized national news, has contributed to a loss of trust in media over the last 20 years, some experts say.

But Antigravity has managed to weather the storms and continue to publish the stories relevant to its readers when they needed it most. That determination — or stubbornness — McGovern said, embodied the city of New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina.

“Hopelessness can sort of breed a determinative arrogance,” McGovern said, “in terms of refusing to go away.”

Fighting off misinformation

Antigravity’s first issue after the storm came out in November 2005, bearing the headline “Down But Not Out.” It included interviews with local musicians and artists about their plans going forward, as well as status updates on venues like Tipitina’s, House of Blues and the Hi-Ho Lounge. It also included a memorial for places that weren’t coming back, like TwiRoPa, a music venue that suffered extensive flooding damage and would have to be demolished.

“National news organizations were more focused on the political aspects of what was going on in New Orleans, everything going on with [New Orleans Mayor] Ray Nagin, everything going on with FEMA, that sort of stuff,” McGovern said. “So it was doubly important for Antigravity to be around, covering the venues like One Eyed Jacks and Dixie Tavern — places that the people of the scene congregated in.”

Antigravity also published content pushing back against misinformation about New Orleans, including an interview with local artist Ray Bong in which he disputed conservative talk radio host Rush Limbaugh’s claims about political motivations behind response and recovery efforts.

“People in New Orleans are not concerned about those kinds of issues anymore, about who’s the Democrat and who’s the Republican,” Bong said. “We’re worried about what’s going to happen to our city.”

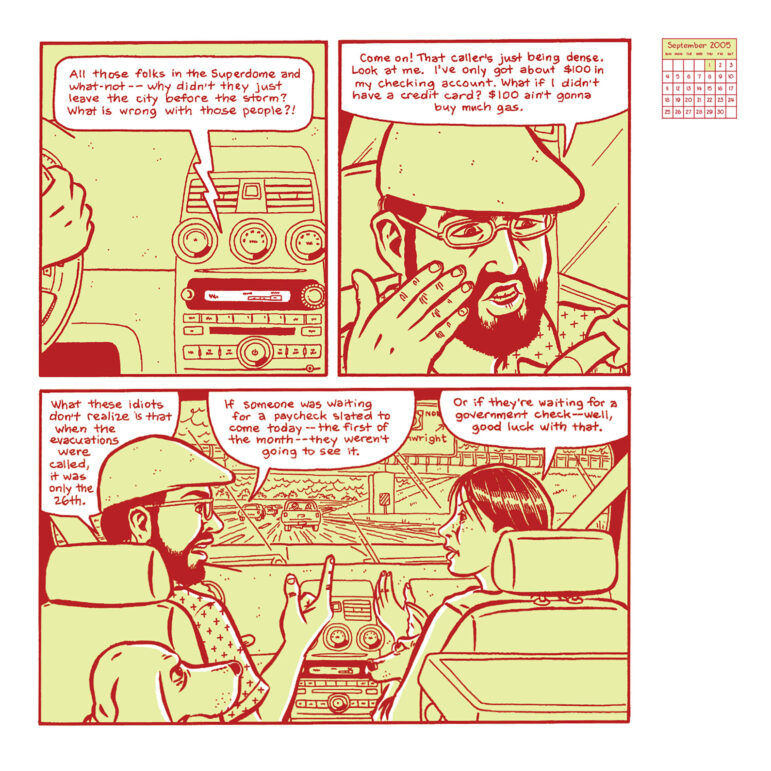

What happened to Antigravity was a microcosm of what was happening across the media landscape. In the aftermath of the storm, rumors were rampant, worming their way up to becoming official statements from officials like New Orleans Police Chief Eddie Compass and Nagin. This included claims of widespread looting, rape and violence, which often turned out to be untrue.

Christopher Drew was among the national journalists working to dispel false claims. He grew up in New Orleans and covered Katrina for The New York Times. He described an “echo chamber” where false information was amplified.

“There were issues, but I think it was just a matter of the things that got exaggerated were exaggerated because the police chief was going around telling people on record and then Nagin was kind of echoing,” Drew said.

Drew helped write articles explaining why the city’s levee system failed, why some residents weren’t able to evacuate ahead of the storm and how many of the “alarming stories” of rape and violence in places like the Superdome and Convention Center were “little more than figments of frightened imaginations.”

The reality, Drew said, was much more grim: thousands abandoned by officials, stranded for days without food and water, left to suffer in squalor and sweltering heat.

‘None of our reporting was showing up in his emails’

Local journalists were also working to report information the moment they found out about it. Mark Schleifstein was a reporter at The New Orleans Times-Picayune. He stayed behind to cover the storm, losing his home in the subsequent flooding. With internet access mostly out of commission, Schleifstein and others took dictated stories over the phone from reporters in the field.

“We’re covering everything that’s happening in the city, and we are covering it 24-7,” Schleifstein said.

The problem, both Drew and Schleifstein said, was that their reporting was missing a key audience. Federal officials were following national TV news, but weren’t looking at reports coming from the ground. The Times-Picayune got a record of then-Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Director Michael Brown’s emails to confirm this.

“None of our reporting was showing up in his emails, which was very disconcerting,” Schleifstein said.

The federal government didn’t respond for days after the levees broke. It wasn’t until President George W. Bush’s aides showed him a compilation of news reports showing the extent of the devastation in New Orleans that the federal response changed.

By that point, national TV news coverage had also shifted. Reporters like Fox News’ Shepard Smith and CNN’s Anderson Cooper grew visibly upset on camera and called for help for the city’s residents.

Dr. Judith Sylvester, an associate professor at LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication and author of the book, “The Media and Hurricanes Katrina and Rita: Lost and Found,”said that before then, there was a “political blindness” to what was happening, with federal officials attempting to downplay the destruction.

“I think it took these reporters being so angry that people began to pay attention,” Sylvester said. “It was like, ‘Whoa, why is Anderson Cooper almost on the verge of tears here? He’s so angry about this.’”

Since Katrina, that “political blindness” has gotten worse, Sylvester said, and national news is even more polarized. The loss of local publications has further contributed to the divide.

“They were the ones who were telling people in their communities. They were trusted,” Sylvester said.

In the two decades since Hurricane Katrina, more than 3,200 local publications across the country have shut down.

This summer, Antigravity almost became one of them. The magazine was in dire financial straits. Its ad-based model — long sustained by struggling local businesses — has been hit especially hard by New Orleans’ worsening summer slump, leaving the magazine with only a few months of fuel left.

But just like it was there for New Orleans residents after Katrina, 20 years later, the city was there for Antigravity. After a plea to readers in the July 2025 issue, the magazine saw an outpouring of support through new advertisers and subscriptions, keeping Antigravity alive.

In a note of gratitude, current editor-in-chief Dan Fox thanked everyone for their support, including local media outlets that helped spread the word.

“Thank you again, truly,” Fox wrote. “Antigravity lives to fight another day.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

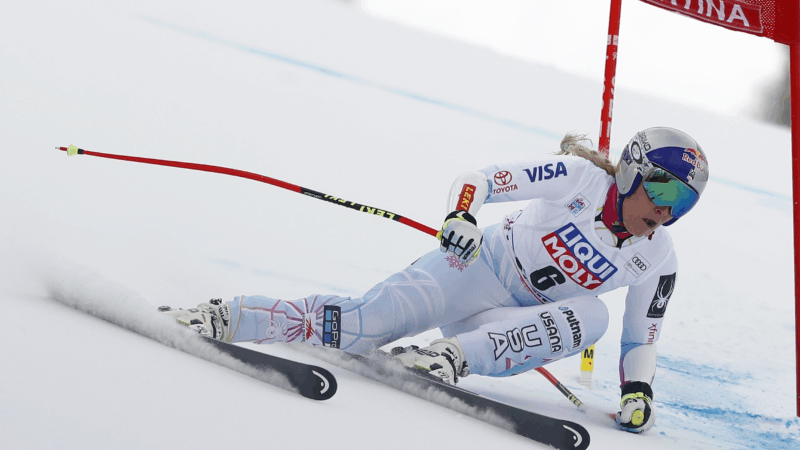

For many U.S. Olympic athletes, Italy feels like home turf

Many spent their careers training on the mountains they'll be competing on at the Winter Games. Lindsey Vonn wanted to stage a comeback on these slopes and Jessie Diggins won her first World Cup there.

Immigrant whose skull was broken in 8 places during ICE arrest says beating was unprovoked

Alberto Castañeda Mondragón was hospitalized with eight skull fractures and five life-threatening brain hemorrhages. Officers claimed he ran into a wall, but medical staff doubted that account.

Pentagon says it’s cutting ties with ‘woke’ Harvard, ending military training

Amid an ongoing standoff between Harvard and the White House, the Defense Department said it plans to cut ties with the Ivy League — ending military training, fellowships and certificate programs.

‘Washington Post’ CEO resigns after going AWOL during massive job cuts

Washington Post chief executive and publisher Will Lewis has resigned just days after the newspaper announced massive layoffs.

In this Icelandic drama, a couple quietly drifts apart

Icelandic director Hlynur Pálmason weaves scenes of quiet domestic life against the backdrop of an arresting landscape in his newest film.

After the Fall: How Olympic figure skaters soar after stumbling on the ice

Olympic figure skating is often seems to take athletes to the very edge of perfection, but even the greatest stumble and fall. How do they pull themselves together again on the biggest world stage? Toughness, poise and practice.