One woman is walking from Chicago to Montgomery to speak out about racial injustice

Rachelle Zola walks ten to fifteen miles a day, pushing a small handcart adorned with a sign that says, “ASK ME WHY AM I WALKING 754 MILES?”

The 76-year-old woman is walking from Chicago, Illinois, to Montgomery, Alabama, to raise awareness of racial injustice in America. She does this by walking and also by performing her one-woman show, Late: A Love Story. In the show, Zola shares her journey of learning about racial inequality and also presents the experience of racism through sharing the stories of her friends. She’ll perform the show Sunday, Aug. 25 at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Birmingham.

WBHM’s Sara Güven spoke with Zola about her journey and performance as she made her way through Birmingham.

The following conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What made you want to take on this project? What inspired you?

I get callings. I got these like, marching orders, I don’t know, from the universe that said, you’re going to Chicago and you’re going to be engaged in the Black and brown community. It was shocking. I’ve never been to Chicago. I didn’t know anyone in Chicago, but I took it quite seriously and I went. And so the first day, I arrived in August of 2019, and from day one, I was meeting the people in the Black community and they told me places to go. They were asking themselves and asking me, “Who are you? Why is this 71-year-old white woman here? And what do you want to do?” And I didn’t even have an answer. I didn’t even know. But I kept showing up. And then I knew because they started sharing their lived experiences.

I say right in my play, this is a tribute to the people that so many people deem as invisible, dismiss, or hate for the color of their skin. And it’s painful to say, and I say it every time, I never even thought about their lives. I didn’t think about the depth of the trauma and the harm that they were experiencing every day. And so me, as a white person now, to hear that in my 70s, it’s shocking to come to this so late knowing that I’ve never been challenged to look at that I live in a racist country. So they share these stories, and I was like, I know what I’m supposed to do.

Why do you think it was that you never were taught or even thought about the experience of racism? Do you think that was because of your upbringing?

I’m asked that a lot. I’m 76. I was born in Brooklyn, New York. At age nine, my parents moved to Long Island, and that’s where I was. And it was a totally white community. I mean, looking back, there were communities that were mostly Black, but I didn’t even meet any. There was not one white-Black family where I lived. It’s crazy. People say to me, “Did you all sit around and just say you hated us?” I said, “We never talked about you. It wasn’t even on my radar.”

It all comes back to no one challenged me. I didn’t even know there were questions to ask. I didn’t even know that I was supposed to ask questions of myself. And yes, it boggles my mind. It’s like, how could that have happened?

Was there any specific thing that happened in our country that changed that in your mind and made you start thinking about this, or was it just your calling as you said?

No, it really was, I was supposed to come to Chicago. You know, people ask me, “Well, what is it about you that’s doing that now?” I have a kid brother. He’s six years younger than me, and he has cognitive disabilities. So I’ve always been an advocate. It’s like you don’t mess with my kid brother. So I have that already, a piece of me. And it didn’t just go to Michael. It could be anybody. If I saw something, it was like, “Hey, you. Don’t treat that person like that.” I looked at Michael and I said, “Hey, uh-uh, you don’t get to harm him.” So that same umbrella that runs my life really became, no, you don’t mess with my Black brothers and sisters. But that didn’t happen until I moved to Chicago. It took me moving to Chicago to learn about my own country.

Can you describe the show, and I was wondering if you would be willing to recite a part of it?

It’s two acts. Act one is more me talking about my life, my lived experiences, how I got here. Part two is very much my friends. I invited ten of my friends, three white, seven Black. I had called them up and I said, “I’m putting this into the world. You just share whatever you want to share. And I will edit it and make a play around you.”

There’s a scene, I’m calling [a woman] because I’m looking for a roommate. She gets on the phone and says, “Hi, my name is Joyce, and I’m Black.” I said, “Hi, my name is Rachelle, and I’m white.”

She said why she said that was because her name is Joyce, and a lot of people associate that with a white name. And she sounds like a white person. So [potential renters] were falling all over each other, calling her, saying we’ll give you the money now. She said no, take your time, I want you to see the place. I want you to meet me.

So she’s coming down from the condo and she’s letting people in. The front of her lobby entrance is all glass, they see her, she’s Black, and they turn away.

She said, “You know what? I put up with that at work, but not in my home.” So that’s why she said, “Hi I’m Joyce, and I’m Black.”

I wanted to ask you about the walk portion of your project. What were you expecting from this journey? And what has the reality been like, especially walking and doing this project in the Deep South?

I [came] down South thinking that I’m going to hear, “hell no, because we don’t want them here.” I haven’t gotten that. I haven’t gotten that and I honestly did think I would.

I think the biggest surprise for me is the kindness all the way along the route. People who want to participate with what I’m doing in whatever way that looks like: giving me a ride, giving me a meal, just speaking with me, taping one of their stories, coming to the show.

What was it about walking that made you want to do that as the means to fight racism and racial disparity?

I enjoy walking, and I’m shocked by how empowering it feels for people to hear that I’m walking. It’s this idea that I’m willing to take the time that I wasn’t looking at it as empowering as other people looking at it.

It’s really, thank you for taking the time to walk. Thank you for taking the time to meet people along your route. Thank you for whatever that looks like. I don’t even have the words for it because I’m actually surprised of the impact when someone hears I’m walking. It’s like, you’re walking. You’re willing to do this. You’re willing to get tired. You’re willing to just keep talking to people. You’re willing to put this white body out there for people to see.

I can’t tell you how many times people start conversations and say, “We’re just supposed to love each other.” And that seems to come out of the power of walking and seeing them. And just standing there and just laughing, or crying both, all within a few minutes. And we just met.

The walking allows that vulnerability. I mean, I’m just hanging out there by myself, right? Walking down streets that I don’t know anyone on. It’s like, what are you doing here? It gives permission again to be vulnerable, to share their truths.

I wanted to ask you, how would you respond to people that hear about what you’re doing, and they respond in a way that’s like, “Oh, this is just another white person making this big societal issue about themselves, something that they’ve never experienced personally”?

Actually, I’ve never had pushback that way. I didn’t come with an agenda. I didn’t come with money. I didn’t come with anything except showing up. So I think that’s why, I know that’s why I don’t get pushback. Because I didn’t come to fix anything.

You know, the white person who does something, they come with their money, they come with their ideas, they say, “Oh, we’re going to do this.” And then it doesn’t work out the way they think. And then they blame the Black community. But they had come with their agenda. And I think that’s a very big difference. I didn’t come with any agenda. I just came because I was supposed to and I was supposed to show up, and I did every day. So that’s what I would tell people.

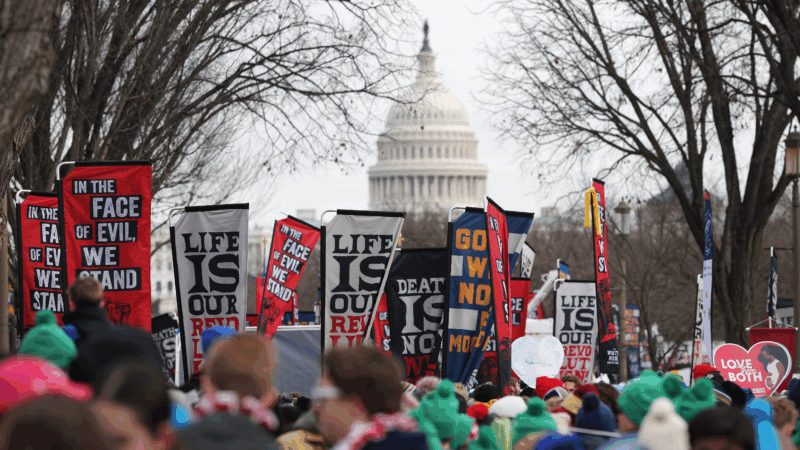

March for Life attendees may have been exposed to measles, DC Health warns

D.C. health officials are contacting people possibly exposed to measles at the March for Life in January, as confirmed cases rise nationwide.

U.S. gave Ukraine and Russia June deadline to reach peace agreement, Zelenskyy says

"The Americans are proposing the parties end the war by the beginning of this summer," Zelenskyy said, speaking to reporters on Friday.

U.K. leader’s chief of staff quits over hiring of Epstein friend as U.S. ambassador

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer's chief of staff resigned Sunday over the furor surrounding the appointment of Peter Mandelson as U.K. ambassador to the U.S. despite his ties to Jeffrey Epstein.

Trump administration lauds plastic surgeons’ statement on trans surgery for minors

A patient who came to regret the top surgery she got as a teen won a $2 million malpractice suit. Then, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons clarified its position that surgery is not recommended for transgender minors.

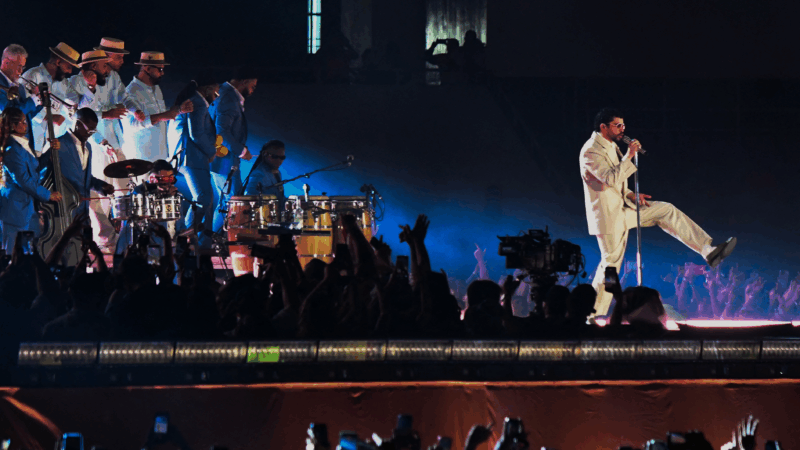

What you should know about Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show

Will the Puerto Rican superstar bring out any special guests? Will there be controversy? Here's what you should know about what could be the most significant concert of the year.

Sunday Puzzle: -IUM Pandemonium

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with KPBS listener Anthony Baio and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.