Inflation is slowing, unless you’re ‘makin’ groceries’ for New Orleans gumbo. Here’s why

New Orleans chef Bunny Young spoons piping-hot gumbo from the pot in her home kitchen on Dec. 8, 2023.

By Stephan Bisaha and Drew Hawkins/Gulf States Newsroom

Decked out head to toe in crawfish red — from her dangling crawfish earrings down to her Crocs — New Orleans chef Bunny Young makes her way up and down the aisles inside Zuppardo’s Family Market, one of the oldest supermarkets in the New Orleans metro area.

She’s looking for ingredients to make what she calls a “7th Ward Gumbo,” a weekly staple on her menu — especially once the temperature drops. When asked what makes a 7th Ward Gumbo different from other gumbos, her reply is simple.

“A 7th Ward girl made it,” she says with a laugh.

Young does pop-ups at bars and events around the city, and she often cooks out of her own home, selling pickup orders to-go or delivering them through food delivery apps. Business has been going well. Last year, she was able to leave behind a 25-year accounting career and switch to cooking full-time.

But lately, rising food costs have made it more difficult.

“Everything’s going up, definitely compared to last year,” Young said. “What it cost me to make a large pot of gumbo, I’m gonna get maybe three-fourths of that now at the same cost. So we’re feeling it.”

Despite years of budget-squeezing inflation, economists ended 2023 with positive news and an in-vogue economic term — disinflation. It means the rate of prices rising has slowed — according to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which The Bureau of Labor Statistics uses to track the cost of an average “basket of consumer goods.”

But while this works when tracking inflation nationally, it often fails to capture it for regional specialties, like many of the ingredients needed to make Young’s gumbo.

“I can tell you that list is not what’s happening,” Young said, challenging the numbers in a recent CPI report. “That government website, that’s not what’s happening.”

Making a pot of gumbo can give a unique look at the regional impacts of disinflation in a way the CPI can’t. And what better way to illustrate this than shadowing Young in her kitchen as she follows her recipe, and counts the cost.

First, you make a roux

Any good gumbo starts with a roux — a base of flour combined with some form of fat.

Here’s where the first indicator on Young’s Gumbo Index — as we’ll call it — appears. The price of flour is rising across the country, but it’s rising a lot faster in the South than it is nationally — nearly 7%, according to the CPI.

Like with flour, the CPI reports a lot of variations in food inflation across the country. For instance, the price of romaine lettuce is dropping at a faster rate in the Midwest. And in the Northeast, potato chips are getting comparably more expensive.

There are a couple of factors driving the inflation variation, like the difference in rent and labor across the country. Those costs get passed down to consumers through higher prices. Looking beyond food, the cost of housing is the major driver for differences between regions, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Additionally, shipping costs vary, which can explain some pricing differences — especially when it comes to perishable foods.

Adding the Holy Trinity

Young’s gumbo recipe calls for vegetables once the roux is ready to go — specifically, celery, onion, and green bell pepper. In Louisiana, these are known as the “holy trinity” and are the base of many dishes.

Here, the CPI reports good news. Fresh vegetables are cheaper compared to this time last year by more than 3%.

Young, however, is not seeing this in New Orleans — at least when it comes to bell peppers.

“These are two for 89 cents,” Young said. “This is expensive in today’s culture.”

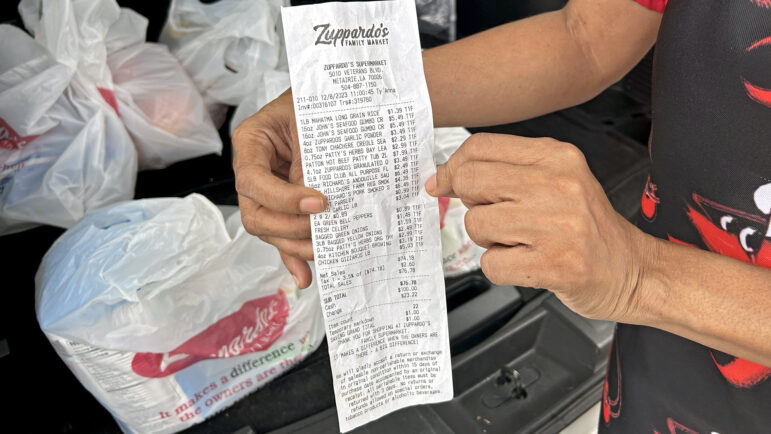

While many of Young’s price comparisons to last year were recalled by memory, she had the receipts to back up the nearly 14% bump she’s been paying for bell peppers — a huge difference from the drop in prices the national CPI reports for fresh vegetables.

Young isn’t alone in feeling there’s a disparity between what the government says the economy is doing and what they’re seeing in the grocery store. Consumer sentiment for the current economy is worse than what it should be given official economic indicators, and it’s even worse in the South, where many are blaming rising prices for their financial hardships. Disinflation also isn’t felt the same way in the South, where inflation is still higher than it is in the rest of the country.

David Wessel, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution, does not dispute their regional differences when it comes to inflation but does defend the CPI as an accurate measure of where inflation is going overall

“The people at the Bureau of Labor Statistics are incredibly precise and practical,” Wessel said. “They know what their surveyors told them the price was a year ago and that’s a lot better than our memories.”

How the sausage is made

Another gumbo essential for Young is smoked andouille sausage. While she preps and chops her trinity, she’s got sliced andouille browning in a saucepan on the stove next to the roux.

Andouille is, arguably, the quintessential smoked sausage of Louisiana. It’s crucial for dishes like jambalaya, red beans and rice and, of course, gumbo. But if you try to look for it in the CPI, you won’t find it.

That’s because the CPI does not track regional specialties. Andouille, however, is made with pork, which according to the CPI has been pretty immune to inflation over the past year. It’s practically the same price compared to a year ago — down half a percent.

But like bell peppers, Young is not seeing that small decrease. For her, the price of andouille has gone up.

“These are $6.50 each,” she said, holding up a package of andouille sausage. “I can remember they were…I’d say five bucks last year.”

The CPI does look at specific regions, like New England, the Bay Area and the South, and it weighs goods differently for each area based on people’s budgets. For example, housing is weighed more heavily in the South than it is in the Midwest. This, combined with home prices and rent rising faster in the South, explains why the region has higher overall inflation.

And even if pork stayed virtually flat this year, the price of pork is still up 18% compared to three years ago — not much to celebrate if you’re still missing those pre-inflation prices.

The South also isn’t a monolith.

For instance, while andouille is the king of smoked sausages in New Orleans, a shopper in Birmingham might opt for Conecuh sausage and still run into the same issue.

What sausage — or other groceries — get put in the CPI’s basket of goods matters a lot, so leaving out the andouille that Young uses in her gumbo might mean missing a big inflation spike hitting people in New Orleans.

Ben Meadows, an assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Collat School of Business, said the CPI is asking a different question, looking for the overall trends of disinflation across the country.

“They’re trying to figure out what, overall, sausage is doing,” Meadows said. “You’re trying to get a basket of goods that represents a shopper in Seattle, New Orleans, New York and Nashville all at the same time.”

Eating it up

Once the andouille is browned, Young stirs the trinity and the sausage into the roux and fills the pot with seafood stock she made using crab shells. She also adds in an assortment of chicken gizzards, peeled shrimp and lump crab meat. She turns up the heat and waits until the gumbo comes to a boil, then turns down the flame to let it simmer for hours.

And then, finally, it’s ready for the most important test: the taste test.

Young places a scoop of fresh steamed white rice into a bowl and adds ladlefuls of the rich, bountiful steaming liquid into the bowl, garnishing it with a crab claw. She sells her gumbo by the quart and she said she’s had to up her prices from $10 to $15 — a 50% jump — to make up for her costs increasing.

The result? Her customers have started to ask for smaller, cheaper portions. But even with the price increase, they’re still eating it up — she always sells out. One taste and it’s easy to see why.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

When a horse whinnies, there’s more than meets the ear

A new study finds that horse whinnies are made of both a high and a low frequency, generated by different parts of the vocal tract. The two-tone sound may help horses convey more complex information.

Trump’s many tariff tools mean consumer prices won’t go down, analysts say

The Supreme Court struck down President Trump's signature tariffs. But the president has other tariff tools, and consumers shouldn't expect cheaper prices anytime soon, economists say.

Hundreds of American nurses choose Canada over the U.S. under Trump

More than 1,000 American nurses have successfully applied for licensure in British Columbia since April, a massive increase over prior years.

Tax credits for solar panels are available, but the catch is you can’t own them

Rooftop solar installers are steering customers toward leases instead of purchases. Federal tax credits for purchased systems have ended but are still available for leased ones.

5 takeaways from Trump’s State of the Union address

President Trump hit familiar notes on immigration and culture in his speech Tuesday night, but he largely underplayed the economic problems that voters say they are most concerned about.

China restricts exports to 40 Japanese entities with ties to military

China on Tuesday restricted exports to 40 Japanese entities it says are contributing to Japan's "remilitarization," in the latest escalation of tensions with Tokyo.