Gun violence and incarceration issues go ‘hand in hand’ in this Louisiana city, residents say

Carl Law and his son, Blaze, stand on a porch in the Lakeside neighborhood of Shreveport, Louisiana, on April 18, 2024. Law, whose father was incarcerated throughout his school years, said children losing their parents to lockups explains why the area’s violence has not improved.

Editor’s Note: This is Part 2 of a three-part series examining gun violence and incarceration in Shreveport, Louisiana. You can read other entries in the series here:

- Part 1: In the fight against gun violence, this Gulf South city is searching for ways to save lives

- Part 3: Q&A: Prison reform advocate Terrance Winn on gun violence in Shreveport, Louisiana

On a friend’s red-and-green-painted porch in the Lakeside neighborhood of Shreveport, Louisiana, Carl Law is wrangling his two-year-old son, Blaze.

Anxious for his dad’s attention, Blaze pulls on his dad’s T-shirt. The toddler’s interruptions burble beneath Law’s voice as he describes his relationship with his own father — one built through jail phones.

“He stayed in my life through the jail, still,” Law said. “He made sure he called me. But a lot of people don’t have that.”

Law is among a few Shreveport residents who point to mass incarceration as a contributor to the area’s gun violence.

“Most parents [are] locked up a kid’s whole life. They’ve been putting people away, not trying to help,” Law, who works as a box truck driver, explained. “So what you think the kid is going to come out to be like, when they got no dad in they life, to try to teach them the right way to come up?”

Last year, a burst of homicides rattled Shreveport. This year, high-profile gun crimes such as the shooting death of a 1-year-old child have stirred outrage.

But incarceration also touches many of the city’s families.

A larger share of Shreveport residents is in prison compared to bigger Louisiana cities — like New Orleans and Baton Rouge, according to a 2023 review by Voice of the Experienced, the Prison Policy Initiative and a data-analysis group. An overcrowded parish jail has vexed officials.

It’s a microcosm of a larger Gulf South challenge. Federal data show Louisiana and Mississippi led the nation in imprisonment rates in 2022, while Alabama’s prison system is both overcrowded and in chronic turmoil.

Law is a friend of gang violence intervention organizer Robert Bruchun. He said his father was incarcerated during his elementary school years, and he didn’t get out until he was going into his senior year of high school.

Against the odds, they maintained a close relationship, with Law even feeling scared to report to his dad when he misbehaved.

While community members sometimes step in as father figures, Law said losing dads to lockups — paired with few good jobs and dwindling activities for young people — explains why this area’s violence hasn’t improved.

“They just want to lock everybody up, send them to jail and think that’s going to stop it. But that ain’t gonna never stop it,” he said.

‘We’re living in the epidemic’

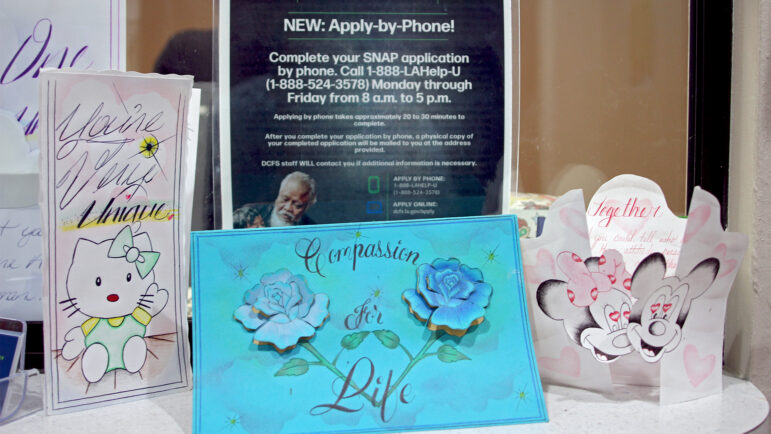

At Compassion for Lives on Pines Road, hand-drawn cards are taped up in the front window of the office shared by social worker Vanessa Smith and executive director Carla Buntyn. The two said they regularly visit jails for pre-release counseling and support services.

Decades ago, they watched their community begin to change — including mounting losses to families.

“I’d say it probably took a turn in the mid-80s to late 80s,” Smith said.

“The late 80s and the crack cocaine epidemic,” Buntyn agreed. “That’s when you [saw] the men leave the homes. They were no longer there. They were, guess what? Incarcerated.”

In their telling, that era of the community’s history destabilized households. Moms struggled, and the ensuing impacts rippled through generations. That’s especially been true in cases where young people became pregnant and left school to raise kids, they said.

Buntyn draws a direct line between past problems and recent violence in Shreveport.

“What you see today, 14-year-olds killing each other, this is the outcome [of] that crack cocaine epidemic,” Buntyn said. “We talk about it all the time. We’re living in the epidemic. This is it.”

For young clients caught up in violence, social worker Vanessa Smith said economic strain, drug use and trauma — what public health experts call adverse childhood experiences— have often come to a head.

Their organization tries to connect clients and community members with social services like housing assistance, job training and education. The idea is to strengthen communities and break cycles of poverty and crime.

Smith said they’re also trying to mitigate harm that can happen in custody.

“A lot of times they’re in a crisis when they go to jail, they get traumatized in jail, and they come out in that same crisis mode again,” she said.

‘They all work hand in hand’

For Democratic State Rep. Joy Walters, the legacy of mass incarceration is synonymous with gun violence in Shreveport.

“They all work hand in hand,” she said.

Walters, whose district covers part of the city, sits on the state’s House Administration of Criminal Justice committee. She said the area’s crime comes up almost every day in conversations with her constituents.

At the same time, many of the people she talks with have had a parent in prison.

Earlier this year, Walters held town halls to inform the community after a package of new “tough-on-crime” laws — including changes to how 17-year-olds are charged, good-behavior release credits and parole — galloped through the legislature.

“My district is impacted — all districts are impacted — by these pieces of legislation. Because people will sit for longer in jails,” she said.

It will take a concerted effort by law enforcement, community organizers, religious leaders, and even people involved in crime, to take on gun violence in her area, Walters said. She respects her statehouse colleagues, but “us making laws out of fear, it’s still not solving the issue.”

Back on the red-and-green porch, Law’s little boy gets restless, wriggling on his hip. At one point, Law directs him inside to get a drink of water or tells him not to touch some bleach on the porch.

As a parent in this community, he said there’s a lot to worry about.

“By him being a young Black man in this world? Yes, I think about that all the time,” Law said.

He wants the city to create more opportunities for young people like Blaze and his older child, who’s in school. He said he got his box truck in hopes of building something that his kids could inherit from him after he dies.

He also wants to be a good dad, like his own father.

The violence he’s seen growing up in Shreveport, “make[s] me want to be in my son’s life even more,” he said. “It make[s] me want to raise him right, and teach him the right thing.”

“My daddy taught me the right thing. He was in my life; he just went to jail. He just wasn’t here physical[ly]. But my thing is, I want to make sure I be here physical[ly] for him, you know?”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

U.S. and Iran to hold a third round of nuclear talks in Geneva

Iran and the United States prepared to meet Thursday in Geneva for nuclear negotiations, as America has gathered a fleet of aircraft and warships to the Middle East to pressure Tehran into a deal.

FIFA’s Infantino confident Mexico can co-host World Cup despite cartel violence

FIFA President Gianni Infantino says he has "complete confidence" in Mexico as a World Cup co-host despite days of cartel violence in the country that has left at least 70 people dead.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

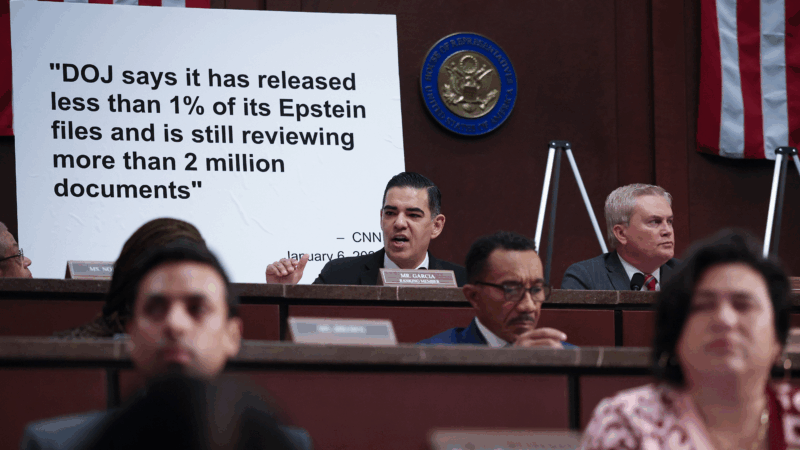

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

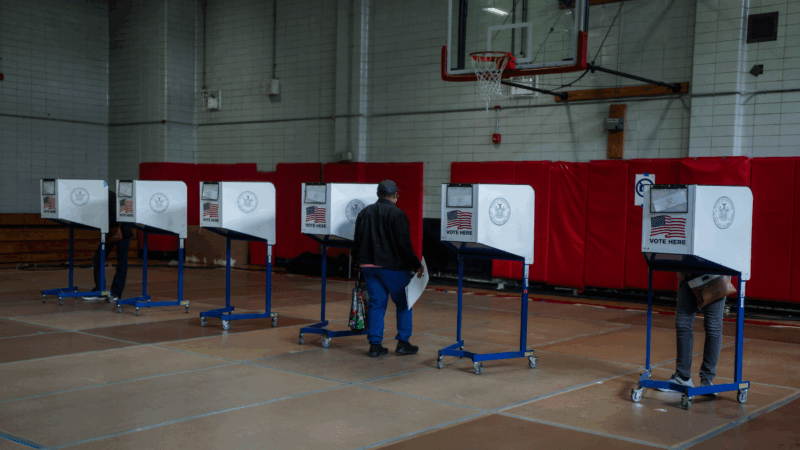

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.