From scrap to sculpture: Joe Minter’s art reflects Birmingham’s pain and joy

Artists often use their surroundings to influence their work. In the case of Birmingham artist Joe Minter, his sculptures can’t be separated from his life in the city – literally.

A site-specific exhibit in Titusville recently honored Minter’s legacy. “Joe Minter is Here” highlighted Minter’s life and artwork. The exhibit, in a centuries-old steel foundry called Marc Steel, was designed in a circular, labyrinth style. It operated as a history museum and as an art museum. Visitors saw Minter’s artwork, but they also learned more about him.

Tyler Jones is the exhibit’s creative director. He said the location has connections to Minter’s story.

“He applied to work here in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s during a period of unemployment. He and his brother were taken by Bull Connor’s police force and wrongfully arrested. His brother was assaulted by police across the street in what’s now Memorial Park,” Jones said.

But Minter’s work was also an aesthetic match for the warehouse.

“The nature of his work being made of steel and the iron and industrial texture, it really feels of this place, which made train wheels over a century ago.”

Minter creates sculptures using discarded items. Car wheels, bicycle gears, chains and scrap metal are fundamental elements of his pieces.

“In his work in particular, using discarded materials, found objects, to draw these connections between what he would say are discarded people,” Jones said.

He felt that it was important to acknowledge the foot soldiers of the Civil Rights Movement. His work is intended to speak for those who tend to be forgotten.

Although there’s social and political commentary laced within Minter’s work, there is also an element of fantasy and joy.

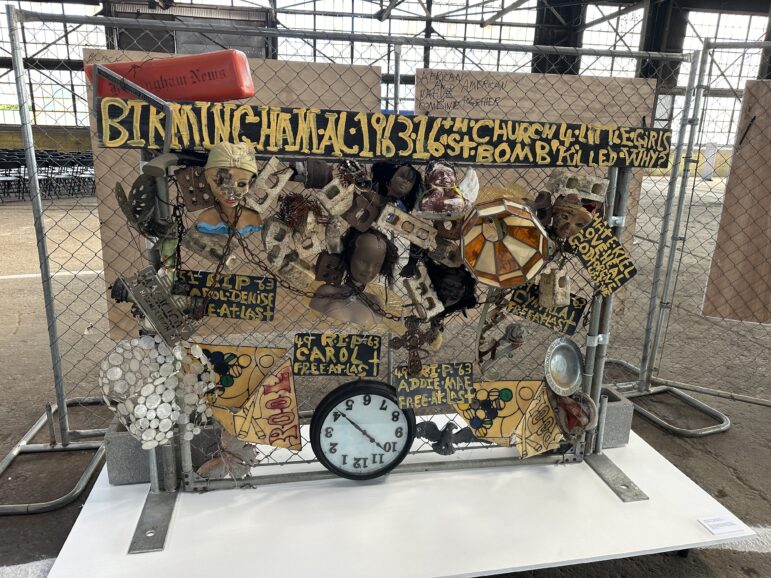

In his piece about the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, the found objects add whimsy. The four little girls who died in the bombing are represented by tattered dolls. Glass shards are made to look like stained glass. Doves and butterflies are woven into parts of the fencing.

Minter’s art shows a different America – one where atrocities take the forefront and the flag symbolizes oppression rather than freedom. But it’s also an art that chronicles survival. That finds joy amidst the pain.

Minter’s open-air museum

Minter became a part of a Deep South tradition called yard shows. Many Black artists resorted to yard shows because art museums were segregated.

“While you might not have access to the museum, the yard became a space to express your ideas about the freedom movement,” Jones said.

Minter’s most popular collection of sculptures, African Village in America, is on display in his yard in Titusville. The street he lives on is lined with his work. It’s an introduction to what you can expect to see in the African Village.

On this day, Minter came to the front gate wearing protective glasses and a hard hat covered in “I Voted” stickers. He showed the space he considers to his studio – a patch of concrete near his front door. Minter said when it comes to his having a studio, he’s happy using nature.

“God contacts you from what’s around you. All of this, all of the stars and the moon and universe, and God is looking down and He can see everything you’re doing,” Minter said.

The space was surrounded by African-inspired sculptures and signage written in his signature font. One piece was recently repurposed from a sign he found at a Goodwill store. Minter said everything about his art is related to Birmingham.

“And when I say everything, the brutality and humility of being whooped and beat, picked up off the street and thrown in a steel mill,” he said.

The African Village is located in the backyard. Minter called it an ancestral burial ground. He said his art environment at his home documents 400 years of the Black experience.

The field of sculptures was a breathtaking sight. It represents one person’s work to allow enslaved Black people to rest in peace. To close out this tour, Minter brought out his drum and banged a rhythm for those who lost their lives during the slave trade.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

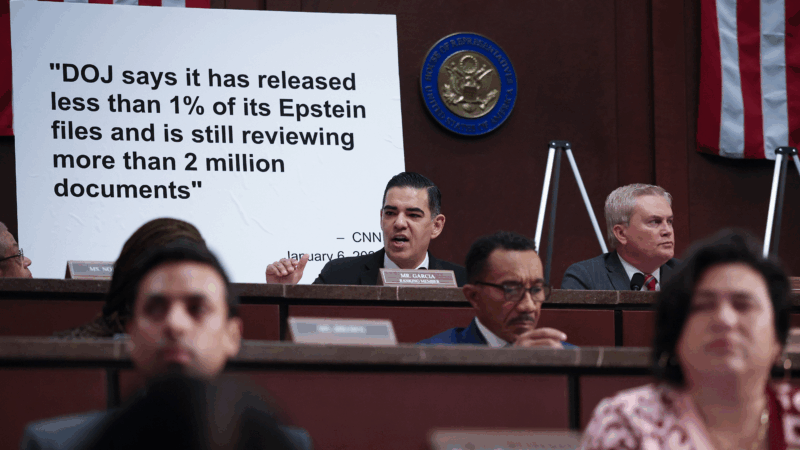

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

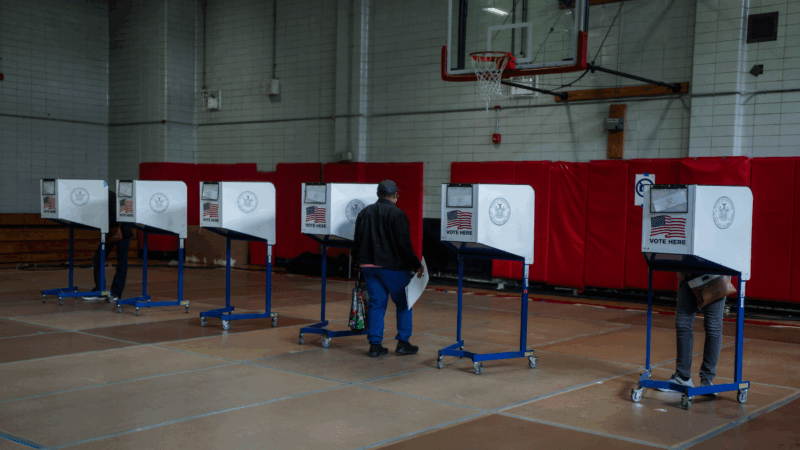

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.

Surgeon general nominee Means questioned about vaccines, birth control and financial conflicts

During a confirmation hearing, senators asked Dr. Casey Means about her current positions and her past statements on a range of public health issues.

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame 2026 shortlist includes Lauryn Hill, Shakira and Wu-Tang Clan

The shortlist also includes a 1990s pop diva, heavy metal pioneers and a legendary R&B singer and producer.