Challenges to forced prison labor gain steam, have resonance in the Gulf South

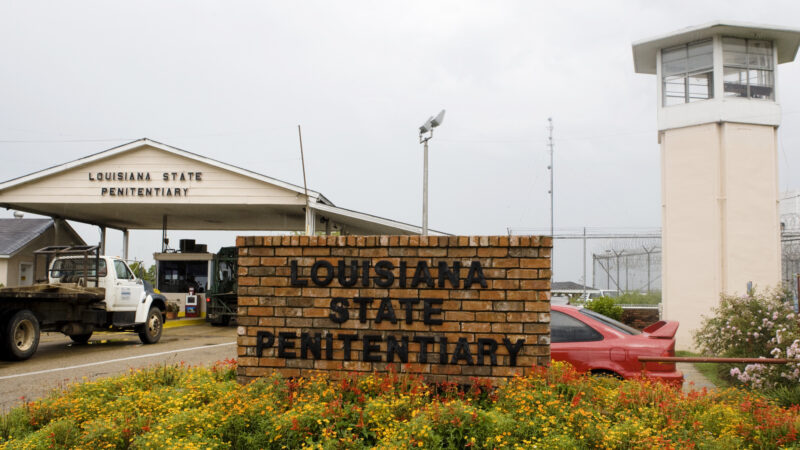

In this file photo, vehicles enter at the main security gate at the Louisiana State Penitentiary — the Angola Prison, the largest high-security prison in the country — in Angola, La., Aug. 5, 2008.

In the nightmare, Chadarius Morehead is in the field at Louisiana State Penitentiary, the prison better known as Angola. It is dark.

He sees an armed prison guard, who orders him to bend down and pick a vegetable. He says no. The guard shoots.

“I’ve woken in a cold sweat, shaking, my heart pounding, and gasping for air,” Morehead wrote of the dream, in a sworn declaration filed in September in a Louisiana federal court.

Morehead wrote the statement as part of a lawsuit brought by incarcerated people, who are objecting to conditions on Angola’s “farm line” — an agricultural assignment at the West Feliciana Parish prison.

Those on the “farm line” describe work units comprising about 50 people per day, attorneys said. In pleadings and interviews, lawyers describe the assignment as marked by tedious fieldwork staged in blistering Louisiana summers.

The sweltering conditions — and meager protections — put people, including people with disabilities, in danger, they allege. In the plaintiffs’ telling, the threat of being sent to the “farm line” is used as a punishment.

“One could just imagine having an armed guard standing over them while, for hours a day, they have to pick grass with their fingers,” said Samantha Kennedy, executive director of the Promise of Justice Initiative, a legal group working on the case.

Kennedy said if incarcerated people refuse to comply with the work they’re asked to do, they risk consequences, such as being sent to disciplinary segregation or not being paid the few cents an hour that help pay for necessities in prison, such as toilet paper.

A spokesperson for Louisiana’s prison system didn’t supply a comment for this story. In court filings, its attorneys have said people working the “farm line” have access to water, shade and rest periods and have filed motions asking a judge presiding over the case to dismiss claims.

Much like people on the outside, Kennedy said people who are in prison want to be productive. But they want to choose the work they’re best suited for, and where they can feel they can best contribute.

Instead, at Angola and other prisons, “people are stripped of their dignity, of their ability to control what happens to their bodies,” she said. “They’re put in grave danger every day.”

The lawsuit, which counts the grassroots group Voice of the Experienced among its plaintiffs, is among at least three challenges to prison labor now percolating in the Gulf South. A few such cases now are winding through Alabama and Louisiana court dockets.

They illustrate a growing movement among people in prison, who are questioning if they can be forced to work against their will. That notion has unique resonance in the South, where the region’s haunted history feels close at hand, experts and advocates say.

They point out that the region’s prisons are disproportionately filled by people of color, especially Black people, some of whom say being made to work at the threat of discipline has historic parallels.

“The question that these prisoners are raising is, is this not slavery?” said Robert Chase, a historian at Stony Brook University in New York who has written a book about prison labor. “They’re bound to the system. They’re coerced to labor. … And in many cases, they’re given either very nominal pay or no pay at all.”

Asking for ‘transformative change’

In addition to the Louisiana lawsuit, a challenge in an Alabama federal court names government officials and corporations as defendants. It alleges that Black Alabamians in prisons are pushed to work at big private companies for little pay, generating profits.

Another Alabama case, filed in state courts and now being appealed, deals with a constitutional challenge to newer state regulations that permit incarcerated people to face consequences for refusing to work. Plaintiffs contend the rules violate recent updates voters made to the state’s constitution.

An Alabama prison system spokesperson didn’t reply to a request for comment on those cases, but attorneys for its officials have made various legal arguments questioning the claims’ validity and asking judges to throw them out.

Emily Early, an associate director for the Center for Constitutional Rights’ Southern regional office, a group working on one of the Alabama suits, said that case’s cluster of plaintiffs is small, but they are asking for “transformative change.”

A victory would “[recognize] incarcerated people as humans, as individuals who deserve the right to work and to be paid fairly for it, to work in safe conditions,” she said.

Simmering prison labor lawsuits in the South join efforts in Colorado, where incarcerated people have sued to challenge forced work in that state’s prisons. California voters went to the polls on Nov. 5 to decide if they should amend the state’s constitution in a way that may limit prison labor on Nov. 5 — mirroring a move in Alabama a few years back.

Experts say forced prison labor exists in part because of a section of the 13th Amendment, which bans slavery and involuntary servitude — except as punishment for crimes.

Generally, prison officials sometimes assert that they need incarcerated people’s work to help maintain the daily operations of detention systems, which are often huge, complex facilities housing thousands of people.

But historically, the South is where prison labor became a big business, including ties to private enterprise, said Chase. He said that dates at least to the Reconstruction Era’s “convict leasing” system and persisted into the 20th century.

“What prisons have done is they have replaced the coerced system of enslavement with a new brand of coercion,” Chase said.

While people in prison across the country have organized against forced labor, he said the South is also where the fight has gained a toehold in courts due to conditions that “physically resembled and reminded people of slavery” more than other regions.

Chase has relationships with people in Alabama’s prison system and follows their strikes and lawsuits. He said incarcerated organizers tend to be acutely aware of the historical context.

While he thinks they are in “a tight spot,” he believes these new lawsuits may gain traction.

Skepticism remains

Back in Louisiana, the “farm line” challenge made headlines this summer when a federal judge ordered the prison system to make changes, such as offering sunscreen and protective equipment.

Lawyers for the incarcerated people have recently moved for class certification that includes anyone at Angola who may be assigned to the “farm line”, which Louisiana’s attorneys oppose, filings show. A trial date was recently put on hold, records show.

Kennedy, of the Promise of Justice Initiative, said the people they represent in the lawsuit are “brave,” coming forward at great personal risk.

“They’re standing up for themselves and for others to say that the future has got to be different than the past,” she said.

Formerly incarcerated advocates also are watching the case with interest. They include people like Bill Kissinger, a writer and advocate, who says he spent more than 40 years in Angola before being released last year.

Kissinger mostly worked in office-based roles while imprisoned, but spent some years working in factories and fields.

“I picked corn, okra, potatoes, tomatoes, hot sauce peppers … ” he said, recounting a laundry list of tasks.

But in an interview, he maintained some skepticism about the “farm line” suit’s outcome. His impression is that Angola is less brutal than when he arrived decades ago, and that the state’s politics, overall, can be challenging.

“I get it that you’re hot. I get it that you’re uncomfortable. I get it that you’d rather be doing something else. But I just don’t see a high probability of success,” he said.

Other advocates with Louisiana ties have been outspoken on the issue, like Shreveport’s Terrance Winn, who entered Angola as a teenager. Since his release, Winn has traveled internationally to speak out on prison labor.

Winn was deposed for the “farm line” suit, per court records. In May, he told a U.S. Senate committee that the only time work stopped in the fields around Angola was when a guard’s horse went down in the heat.

“If a man fell over, we kept working. If you got injured, you kept working,” he said, according to a text of his prepared remarks. “Nothing took precedent over going to work.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Video appears to show U.S. cruise missile striking Iranian school compound

The seven-second video was released by Iranian state media and directly contradicts statements made by President Trump, who said Iran was responsible for the strike.

Crude oil rockets past $100 as markets lose hope for a quick resolution in Iran

Brent crude reached its highest price since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022. Gasoline prices in the U.S. are expected to continue to rise.

Country Joe McDonald, anti-war singer who electrified Woodstock, dies at 84

Country Joe and the Fish's best-known song, "I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag," captured the growing anti-war sentiment of the Vietnam era.

OpenAI robotics leader resigns over concerns about Pentagon AI deal

A senior member of OpenAI's robotics team said guardrails around certain AI uses were not sufficiently defined before OpenAI announced an agreement with the Pentagon.

Trump says he won’t sign bills until Congress overhauls voting

President Trump is pushing the Senate to abandon the filibuster and pass SAVE American Act, a bill top Democrat calls 'Jim Crow 2.0'

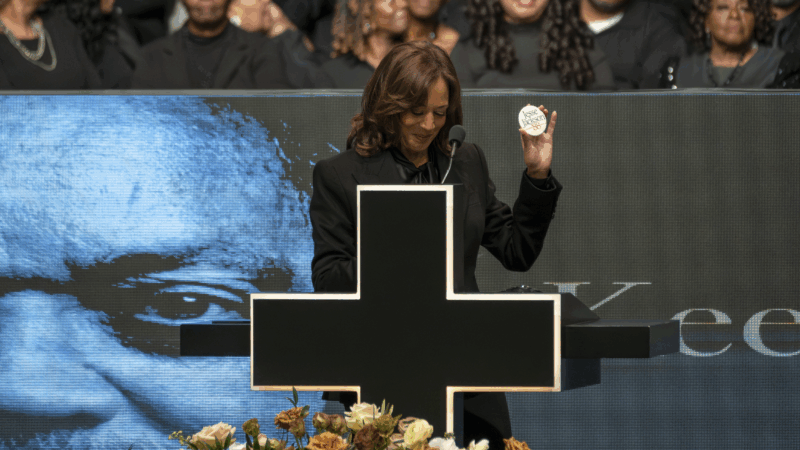

Photos: Scenes from Jesse Jackson’s homegoing services

Thousands showed up in Chicago over the weekend to pay respects to the civil rights leader, who died last month at the age of 84.