Alabama officials hope renovated forensic mental health hospital will reduce backlog in county jails

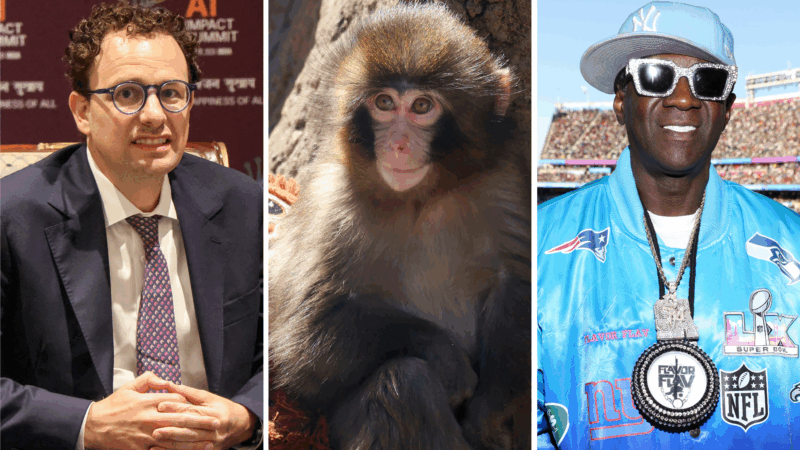

Mark Litvine (L), Daphne Kendrick and Virginia Scott-Adams stand in a program day room, part of the newly constructed section of Taylor Hardin.

For the first time in more than four decades, Taylor Hardin Secure Medical Facility is getting a makeover.

The Tuscaloosa facility, built in 1981, cares for people involved in Alabama’s court system who need mental health treatment. And according to psychologist Virginia Scott-Adams, it reflects an outdated model of care.

“The design of the building was based more on security, so it looks and feels more correctional,” said Scott-Adams, who directs the Office of Forensic Mental Health Services at the Alabama Department of Mental Health (ADMH). “Now, we’ve come to learn about the importance of more therapeutic environments.”

That’s the inspiration behind an ongoing $80 million renovation and expansion to the facility.

Officials hope the improvements lead to better – and faster – outcomes for people who spend months in county jails waiting for treatment.

A hospital, not a jail

Inside the original hallways of Taylor Hardin, sounds echo off the walls, which are lined with heavy metal doors and windows covered with bars.

Facility director Daphne Kendrick unlocks a door, revealing a new area under construction.

“The hallways are much wider. It’s just a more open format,” she said.

The new building is brighter, with windows made from a special glass that doesn’t require bars. The walls are decorated with large murals that feature beach scenes.

Kendrick said it’s carefully designed.

“The colors are set to be therapeutic, calming,” she said. “There’s a lot of light and open areas.”

She said the department wants to make it clear that “this is a hospital, not a jail.”

Competency restoration

Most patients at Taylor Hardin, roughly 75% of the population, are at the facility for inpatient competency restoration.

They have been arrested and charged with crimes, but because of a mental health condition or cognitive impairment, a judge has determined that they are not able to fully understand and participate in the court process.

These individuals typically receive inpatient treatment for several months, before they are considered to be restored and allowed to continue their case.

Scott-Adams said Taylor Hardin has long struggled to keep up with demand, sparking a class action federal lawsuit several years ago.

Recently, the population has been increasing even more.

“If you’re looking at a snapshot of this spring, we received around 30 orders for the month of April, and typically we were receiving about 15 to 20,” Scott-Adams said.

The backlog has resulted in a lengthy waitlist, with people spending months in county jails awaiting a bed at Taylor Hardin.

The experience can worsen their condition.

“When I was in jail, my mental health wasn’t being treated for six months,” said Mark Litvine, who was arrested in Jefferson County in 2012, while experiencing symptoms of schizoaffective disorder. “I would act out, but I would also get jumped. I would walk to the bathroom or get punched. I’ve been choked. I’ve been spit on.”

Litvine eventually transferred to Taylor Hardin and started receiving an antipsychotic medication that helped him stabilize.

State mental health officials hope renovations at Taylor Hardin will help people like Litvine get treatment sooner.

A new model of care

Facility director Kendrick said she expects to move existing patients to the new building at Taylor Hardin within the next few months. At that point, work will begin to renovate the original building, which should be complete by summer of 2025.

When all construction is complete, capacity will increase by about 60%, from 140 to 225 beds.

Scott-Adams said the department is trying to hire more staff to accommodate the expansion. She hopes a more therapeutic space will lead to better outcomes.

“We’re building out a model where patients come in and they’re immersed in treatment and they’re immersed in restoration,” Scott-Adams said. “It creates opportunities for people to achieve those gains more quickly.”

Beyond the walls of Taylor Hardin, state mental health officials are also piloting programs to provide competency restoration services to people while they are in county jails and in the community on bond. If successful, it could help some people recover sooner, reducing demand on Taylor Hardin.

Forget the State of the Union. What’s the state of your quiz score?

What's the state of your union, quiz-wise? Find out!

A team of midlife cheerleaders in Ukraine refuses to let war defeat them

Ukrainian women in their 50s and 60s say they've embraced cheerleading as a way to cope with the extreme stress and anxiety of four years of Russia's full-scale invasion.

Nancy Guthrie case: How do families of missing people cope with the uncertainty?

When a loved one goes missing, relatives can feel guilty simply for eating, says Charlie Shunick, whose sister was kidnapped. Shunick now helps others navigate a nightmare "nobody is prepared for."

As the U.S. celebrates its 250th birthday, many Latinos question whether they belong

Many U.S.-born Latinos feel afraid and anxious amid the political rhetoric. Still, others wouldn't miss celebrating their country

US military used laser to take down Border Protection drone, lawmakers say

The U.S. military used a laser to shoot down a Customs and Border Protection drone, members of Congress said Thursday, and the Federal Aviation Administration responded by closing more airspace near El Paso, Texas.

Deadline looms as Anthropic rejects Pentagon demands it remove AI safeguards

The Defense Department has been feuding with Anthropic over military uses of its artificial intelligence tools. At stake are hundreds of millions of dollars in contracts and access to some of the most advanced AI on the planet.