A family’s search for their native and formerly enslaved heritage in South Alabama

Franklin Tate and his family have spent the last 15 years uncovering their history and finding their family’s property in Little River, Alabama, northeast of Mobile.

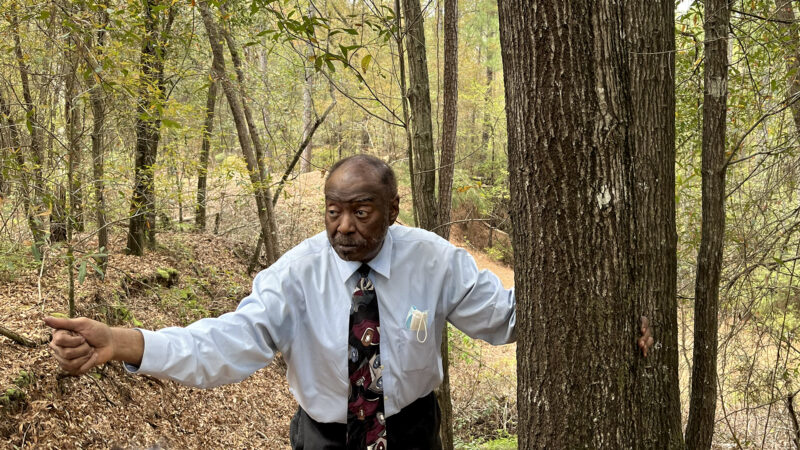

Wilted leaves and pine straw cover the forest floor as Franklin Tate hikes between trees and over-rotted stumps in Little River, Alabama.

Tate, a Birmingham resident, is joined by the University of South Alabama Center for Archeological Studies and the Poarch Creek Band of Indians, on his trek. Together, they’re searching for something lost more than 60 years ago — a house belonging to Tate’s grandparents on the Tate-Moniac Homestead, where they had settled in the early 1900s.

The search for the home has been more than 15 years in the making. Tate’s research began after his aunt found a deed for the parcel of land they were walking through on this cloudy March day. He’s collected records, landrolls and photos ever since.

“The last few years, over the last decade, we’ve been doing that research and I just got blown away,” Tate said.

It’s complicated to untangle, but the story of this land and Tate’s family goes back to before Alabama was a state.

Tate’s third-great-grandfather David was the last chief of the Creek Nation. The Lower Town Creek Indians were allies with America during the War of 1812. When Native people were forced out of Alabama in the 1830s, the Tates were allowed to stay. Former President Grover Cleveland even signed the deed for the Tate-Moniac Homestead.

“We found this deed was sent in 1895 to Todd Tate,” Tate said. “I said, ‘It can’t be Papa. Papa was born in 1880. He would have been 15 years old.’”

After a 45-minute trek through the forest, Tate emerges beneath a canopy of oaks, miles from the nearest paved road. He stares out into a clearing at a brown house with cobwebs and rust in the windows. Purple water irises bloom near the edge of a dirt path that hasn’t been driven over in decades.

“I would have never found it,” he said, and his steps quickened. “Thank God. Thank God.”

Tate said he hadn’t been here since he was a little boy. The original structure burned down nearly 60 years ago and his ancestors rebuilt it. Family members moved away and settled in other parts of the state, leaving the property to the occasional squatter or hunters seeking shelter.

But Tate can remember how the home looked when he visited as a child, with columns and chairs near the front where he could look out into the vast green field.

Tate’s brother, Kenneth, also remembers visiting this land when they were children. He’s not a researcher, but he supports Franklin, whom he affectionately called their family’s own Alex Haley, the African-American author who published “Roots.” Kenneth said it was a relief to uncover this pivotal piece of the puzzle.

“In a state like Alabama, it’s great to know that we did have something to show for the hard work that our forefathers went through,” Kenneth Tate said. “I would love to see something really, really good come out of it for not just us to benefit, but people as a whole. This area has a whole lot of history that I guess we just didn’t know.”

For now, the Tates will continue exploring their acreage in South Alabama, placing pins in the timelines of their history as they go. Franklin said he hopes that in the future, they’ll receive a nomination and a permanent marker from the National Register of Historic Places.

“We are just trying to see what we can access through our story to tell America’s story,” Tate said.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Reporters’ notebook: The Olympics closing ceremony is way more fun than you’d think

Olympics opening ceremonies tend to get more love than their closing counterparts. But a pair of NPR reporters who watched both in Italy left with a newfound appreciation for the latter.

Northeast readies for a major winter storm, with blizzard warnings in effect

New Jersey through Massachusetts could see 2 feet of snow. New York City's mayor said the city had not "seen a storm like this in a decade."

Mexican army kills leader of Jalisco New Generation Cartel, official says

The Mexican army killed the leader of the powerful Jalisco New Generation Cartel, Nemesio Rubén Oseguera Cervantes, "El Mencho," in an operation Sunday, a federal official said.

Ukraine’s combat amputees cling to hope as a weapon of war

Along with a growing number of war-wounded amputees, Mykhailo Varvarych and Iryna Botvynska are navigating an altered destiny after Varvarych lost both his legs during the Russian invasion.

University students hold new protests in Iran around memorials for those killed

Iran's state news agency said students protested at five universities in the capital, Tehran, and one in the city of Mashhad on Sunday.

Pakistan claims to have killed at least 70 militants in strikes along Afghan border

Pakistan's military killed at least 70 militants in strikes along the border with Afghanistan early Sunday, the deputy interior minister said.