1 year after devastating tornado, Rolling Fork mobile home park residents fight to return home

Terri Harden shows an aerial photo of the damage done to the mobile home park that she owned after an EF-4 tornado tore through Rolling Fork, Mississippi, last year on Saturday, March 23, 2024. Harden said she unsuccessfully tried to present a proposal to city officials for a new mobile home park to replace it.

Charles Jones remembers the evening of March 24, 2023, vividly.

He was with his family inside his mobile home in Rolling Fork, Mississippi, when he heard what sounded like hail hitting his roof.

“I looked out the door, I told [my wife], ‘Nah, it’s not hailing. That’s a tornado,’” Jones said. “I told everyone, ‘Get on the floor,’ and I got on top of them.”

Soon, the tornado hit their home and the rest of Jones’ community.

“The house — it went up [and] it came down [three times],” Jones said. “The third time I heard the bedroom window blow out. I knew it was over with then.”

That night ended up being deadly for the Mississippi Delta, as a string of tornadoes left a path of destruction in their wake, injuring at least 165 people and killing 22 Mississippians.

The storms hit Rolling Fork the hardest, where an EF-4 tornado reached sustained winds of 195 miles per hour, leaving 15 people dead. Terri Harden, the owner of the mobile home park where Jones and his family lived, said 11 of her tenants were among that death toll.

Harden has owned the land the park sat on for more than 15 years, but her lot located behind Chuck’s Dairy Bar — a restaurant that’s one of the most iconic places in town — is now empty after nearly every home was destroyed.

“There was one (mobile home) over here that was the only thing that had any sort of resemblance [of] a trailer,” Harden said. “But it was just the framework. Everything else was rubble. Just complete rubble.”

Jones and his family are grateful they survived, but they haven’t been able to return to their home for more than a year after the tornado. Finding adequate temporary housing, for them and their neighbor, has also been a struggle for several reasons.

“You‘d think in a time of need that the town would come together, but if you ask me, the town didn’t come together,” Jones said.

Financial barriers

Shortly after the storm, Harden partnered with a company to begin the rebuild of the mobile home park.

Once contractors started the job, however, Rolling Fork’s housing inspector informed her that the property was in a flood zone, meaning she’d need to raise the elevation level to put housing back there.

This news came as a surprise to Harden, who said she had never seen the park flood during her ownership.

The next blow to Harden’s plan came from the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s response to a petition for temporary housing.

For months, Harden and others in Rolling Fork tried to get the city to advocate on their behalf for the park to be a location for FEMA temporary housing to allow the residents to remain at home. In a letter sent to the city, FEMA said it “made no promises” that it could use the property and explained that the agency prioritized commercial sites that could already be used over sites that would require improvements like Harden’s did.

That meant Harden would need to fix the property before it would be eligible for temporary housing, costing her anywhere from $200,000 to $400,000. That’s money she doesn’t have.

“I owned the trailer park [for] the most poverty-stricken people in Rolling Fork,” Harden said. “I didn’t make very much money.”

Hard to recover

Situations like this highlight the gaps that exist for people who live in mobile homes when trying to recover from disasters, according to Andrew Rumbach, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute — a nonprofit that researches social policy.

Many mobile homes were developed before modern-day rules on where you could put housing — like building codes and zoning laws. The park behind Chuck’s Dairy Bar was built in the mid-80s, and Harden said the city grandfathered it in.

But these modern standards kick in after a disaster, making rebuilding expensive and often permanently displacing vulnerable people.

“If you can’t make it super affordable, then folks just have to move on,” Rumbach said. “And that’s really tough on families.”

Many Rolling Fork residents were already at risk of experiencing these recovery barriers, said Kristin Smith, a lead researcher at Headwaters Economics, a nonprofit research group that studies land use issues in the U.S.

Rolling Fork sits in the Mississippi Delta, where residents face higher poverty rates on average than most of the U.S. For many there, mobile homes operate as affordable housing — in fact, in Mississippi, manufactured houses make up almost 60% of all new single-family homes, according to a manufactured housing website.

Mobile homes are also home to more households of color on average, Rumbach said, and their residents also tend to have other vulnerabilities.

“These are all kind of like red flags to local, state and federal governments that [Rolling Fork] is likely a community that’s going to need a lot of extra assistance and recovery,” Smith said. “And if they don’t get that, to me, it’s going to be very hard for this community to recover.”

Loss of community

Harden isn’t sure what she will do with the land now. It was her livelihood, but for the 32 families who lived there before — including Charles Jones — it was home.

“The little community back there, it was nice,” Jones said. “It wasn’t no rowdy folks you had to worry about. No stealing and none of that.”

Jones said he knew many of his neighbors, including the few who died.

“When I sit up and just think about it sometimes, I relive the tornado over, ‘cause there were some good people back there,” he said. You kind of miss them.”

After the tornado, his family and several others stayed in a motel as they looked for more permanent places to stay.

Jones wishes the town fought harder for the mobile home park to come back.

“If they had let the folk put houses back there, a lot of folks would have been out of the motel sooner,” Jones said.

While everyone is in homes now, they’re scattered, with some staying in other towns. Recovery can take years, and throughout the region, many communities are still working to bring their displaced residents back.

Jones finally found a new mobile home in Rolling Fork in early March, but it wasn’t easy.

He struggled to find an affordable lot before a friend stepped in and offered him a deal. He was paying $100 a month on Harden’s lot, but many landowners in the area have raised their rates to $350 a month since the tornado.

He also got the new home he’s in thanks to Samaritan’s Purse, a nonprofit Christian organization providing aid to Rolling Fork and the surrounding area since the tornado.

“It’s been good,” Jones said of his new home. “Except for the location. I would rather it be back behind Chuck’s.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

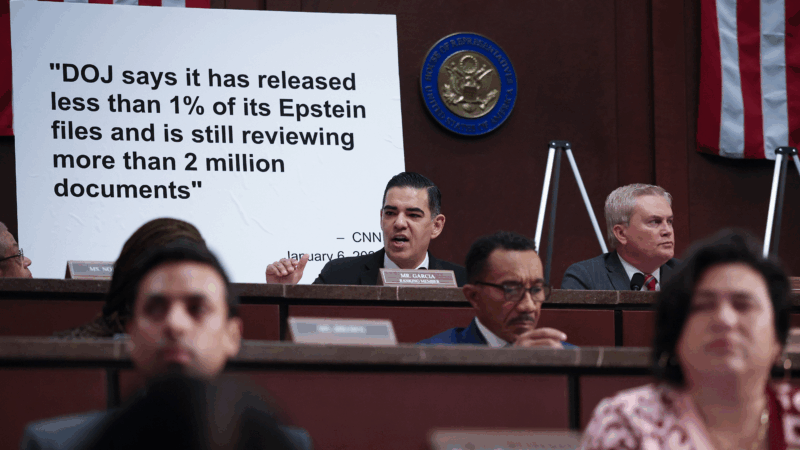

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

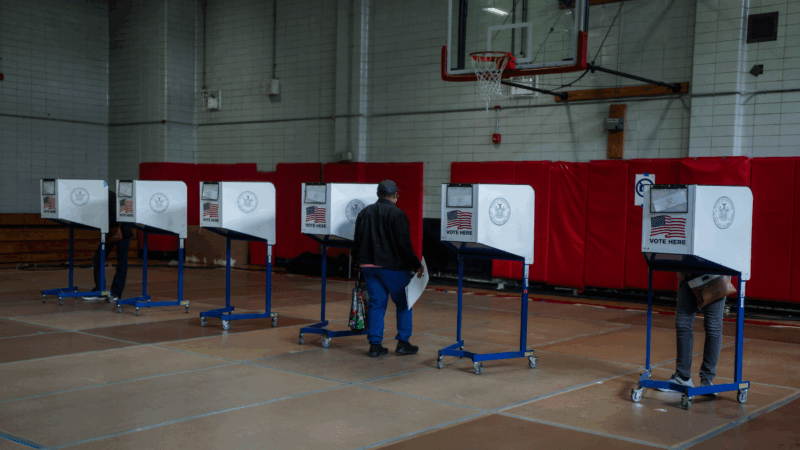

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.

Surgeon general nominee Means questioned about vaccines, birth control and financial conflicts

During a confirmation hearing, senators asked Dr. Casey Means about her current positions and her past statements on a range of public health issues.

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame 2026 shortlist includes Lauryn Hill, Shakira and Wu-Tang Clan

The shortlist also includes a 1990s pop diva, heavy metal pioneers and a legendary R&B singer and producer.