While rebuilding homes, Amish volunteers bond with South Louisiana over faith and food

Keith and Ruth Crosby stand on the porch of their FEMA trailer in Golden Meadow, Louisiana, Jan. 16, 2023. The Crosbys have had help from some Amish volunteers in rebuilding their home after Hurricane Ida. The volunteers are from Amish communities in other states.

Give them space.

That was Ruth Crosby’s first instinct as Amish men and women worked on her Hurricane Ida-damaged home in Golden Meadow, Louisiana last May. She didn’t know if they wanted to avoid photos from the Crosby’s or just have them stay clear of the work — after all, Amish culture has a reputation for being reclusive.

Then, she noticed some of the women eating sandwiches while sitting under a tree. So Crosby decided to offer the volunteers some Cajun hospitality — as in shrimp, catfish and jambalaya.

“I said, ‘If I cook, would y’all eat?’” Crosby recalled. “And she’s like ‘Oh, yes. We love to try different things.’”

That decision led to frequently shared meals — at cookouts on the Crosbys’ land and a supper at the volunteers’ base — along with a connection over their Christian beliefs.

Members of the Amish faith, teaming up with other Christian denominations, are providing what Southern Louisiana storm survivors like the Crosbys need — help, long after the initial aid response has ended. In Golden Meadow, the faith groups have committed to rebuilding homes for at least three years. In Lake Charles, they’re now in their second year.

Residents benefit from the famous Amish craftsmanship. Amish volunteers get to answer a calling from God. And both groups have bonded over hardship, cooking and faith.

“When the end of times are and we’re up in heaven, we won’t have one part for Amish or one part for Mennonite or Catholic,” said Gid Yoder, a member of the building committee for the Amish volunteer group Disaster Aid Ohio. “We’ll all be together up there, so why not help each other down here?”

The Bayou needs help

Golden Meadow sits just south of where the Louisiana marshland narrows and starts ceding land to the Gulf of Mexico. The Crosby’s property — family land purchased from her grandparents shortly after Hurricane Betsy — stretches roughly a quarter mile wide. A levee marks the edge of the west side. The east ends with a highway leading south to Port Fourchon, known for its oil trade.

Crosby stayed for Hurricane Zeta in 2020, a late-season Category 3 storm. She knew better than to do the same for Hurricane Ida a year later, which made landfall just shy of being a Category 5.

The high winds stripped most of the roof off of the house, leaving the interior exposed to rain. The water eroded the floor and walls, along with irreplaceable mementos.

“My wedding picture was all wet…and just bleeding,” Crosby said. “That’s something you can’t get back.”

She was able to find lumber — cheaper to ship it from Alabama than paying for the gouged local prices — but struggled to find a reputable contractor, a familiar problem after Louisiana storms.

“So many contractors were out here messing people over,” Ruth said. “I had one contractor come out here and quoted me a price of $106,000 to redo my house. I can’t do it. I mean, I don’t have the funds to do it. We live off of social security.”

As she was running out of options, Crosby had a chance encounter with Matthew Chouest, pastor of First Baptist Church of Golden Meadow. He told her about an alternative — an Amish group committed to rebuilding homes in Golden Meadow.

Amish volunteers answer the call

It’s a long drive from Lancaster, Pennsylvania to the Louisiana Bayou — especially when you don’t drive. Yet busloads of roughly 40 Amish volunteers with the group Community Aid Relief Effort, or C.A.R.E., make the trip back and forth to Golden Meadow every two weeks. The organization has assisted with disasters in several states, including Mississippi and Alabama. In Golden Meadow, the volunteers stay for about two weeks before a new group comes in.

Traditionally, Amish wrap up their education with the eighth grade before moving to some form of apprenticeship — often learning the type of craftsmanship that makes them ideal volunteers for rebuilding homes.

C.A.R.E. came to Golden Meadow through a pastor phone tree — the organization called one pastor after Hurricane Ida, but he said his community wasn’t hit so badly. So, he directed the group to Chouest.

While Amish culture is believed to be anti-technology, a better description of their belief is being tech skeptics. Many have phones and some even have limited-use computers to send business emails.

Amish is a denomination of Anabaptist Christians. Conversion isn’t the goal for the volunteers. Still, faith does drive them to aid work — a belief that this life is in preparation for the next and that it’s God’s will to help those in need.

“The Bible teaches us if The Lord helps you, you need to help other people,” said Yoder. “If you see someone that’s cold and you tell them ‘Be warm,’ but you don’t don’t do anything about it … then you’re not helping.”

What makes Disaster Aid Ohio and C.A.R.E. unique from other aid is their commitment to long-term recovery. In Golden Meadow, the group committed to at least three years of helping rebuild homes. As long as others provide the materials, the volunteers will handle the labor.

In the Crosbys’ case, C.A.R.E. spent eight days working on the house for free. The volunteers installed new rafters, subflooring and a roof. Women in traditional Amish dresses bolted in hurricane brackets with a power tool Crosby’s husband, Keith, described as “bigger than them.”

Chouest said outside of a few small groups who came to help for a week or so over the summer, most of the other aid that came to Golden Meadow is now gone.

“It’s not just like putting a tarp on your house and out of sight out of mind,” Chouest said. “We want to see you walk into your finished home and have some normalcy again.”

Aid stretched thin

Lake Charles has its own faith-based restoration efforts ongoing thanks to Amish volunteers from Ohio, a national Mennonite group and the region’s Methodists.

The Southwest Louisiana city suffered from two Hurricanes in recent years — Hurricane Laura in 2020 and Hurricane Delta just six weeks later. Mennonite Disaster Service has been in the city for more than a year repairing homes and, in some cases, building new ones. The organization works closely with Amish volunteers, like Disaster Aid Ohio, and the two faith groups hold similar traditions. The Mennonite Disaster Service also believes in long-term aid.

“We’re not necessarily the first organization to respond to a disaster, but it’s not uncommon for us to be the last ones to leave,” said Phil Helmuth, the southern Louisiana response coordinator for MDS.

The organization currently has 15 disaster sites across the country, according to Helmuth — five of which they partner with Amish volunteers. But the increase in the country’s natural disasters, due in part to climate change, has stretched the group. So, there are four factors MDS uses before deciding which of the many communities in need of help to make the long-term commitment to.

The first is making sure they have enough volunteers, of which they usually get about 5,000 throughout the year. Since many members of the Amish faith are farmers, the Amish sites often stick to the colder months outside of planting and harvesting seasons.

Next, MDS helps people not able to recover on their own. The third factor is being able to team with other organizations that can pay for the materials needed for rebuilding. Finally, they need a spot to house the volunteers. The biggest concern for Helmuth in Southern Louisiana, after so many disasters, is the money.

“(Hurricane) Katrina really, really began to stretch us and we increased our response dramatically after,” Helmuth said. “So it seems like the more disasters we have, the more stretched we are.”

Sharing fish and scriptures

As one of many appreciation gestures, The Crosby’s gave the Amish volunteers a five-gallon bag of catfish. The volunteers grilled them up and invited Ruth and Keith Crosby to the base to share the meal. They both enjoyed the fish, though reluctantly admitted to a preference for their liberally buttered, Cajun version.

“We don’t worry about cholesterol,” Ruth laughed.

C.A.R.E. temporarily left Golden Meadow last May so many of the farmers that volunteered could return to work their land. Today, the Crosby’s house isn’t liveable, yet. Everything from the ceiling to closing up the walls remains on the to-do list. In the meantime, they’re staying in a FEMA trailer.

In January, C.A.R.E. came back to town and offered to work on their house again, but Ruth declined the help — telling the group that there are many other people in town who still need help more than she does. She at least has a roof again — and a grant from Restore Louisiana to finish the work through a contractor.

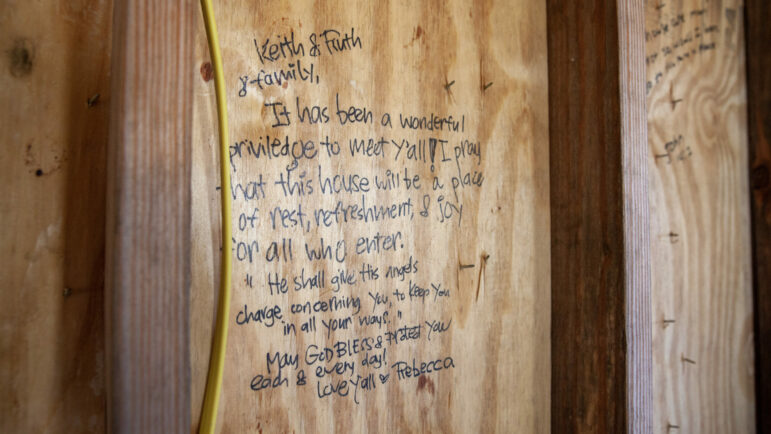

Wandering through the unfinished home now, scriptures written by Crosby are visible on its wood panels. The Amish volunteers added their own Bible passages to them — another sign of the bonding between the group and the Crosbys.

One volunteer left a personal message, writing that it was a privilege to meet the family and that she prays “this house will be a place of rest, refreshment and joy for all who enter.” As Ruth read the note, written on wood that will one day be hidden behind insulation and an interior wall, her voice cracks.

“This is Godly people,” she said. “And if [there’s] anybody I want working on my house, yes, it would be Godly people.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration among Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama and WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

In Berlin, there are movies, there’s politics and there’s talk about it all

Buzz around whether the city's film festival would take a stance on the war in Gaza has dominated conversation in recent days.

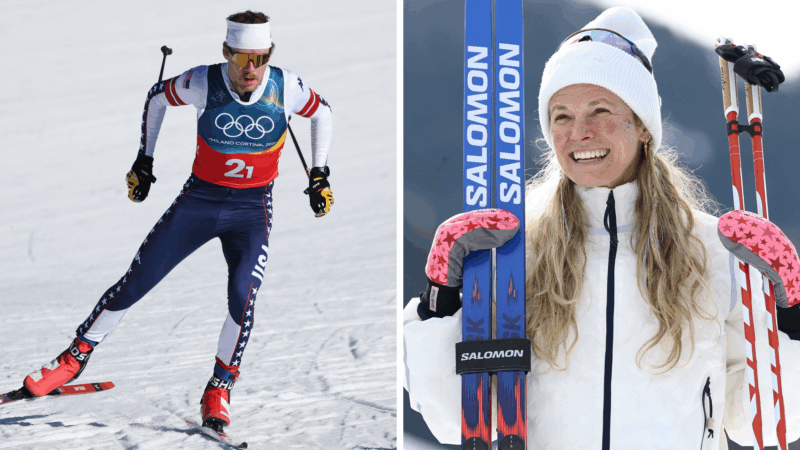

Alex Ferreira wins 10th gold medal for Team USA, matching America’s highest total in Winter Olympics

Freeskier Alex Ferreira clinches a tenth gold medal for the U.S. in these Games, tying the U.S.'s all-time record for gold medals in a Winter Olympics.

Trump calls SCOTUS tariffs decision ‘deeply disappointing’ and lays out path forward

President Trump claimed the justices opposing his position were acting because of partisanship, though three of those ruling against his tariffs were appointed by Republican presidents.

The U.S. men’s hockey team to face Slovakia for a spot in an Olympic gold medal match

After an overtime nailbiter in the quarterfinals, the Americans return to the ice Friday in Milan to face the upstart Slovakia for a chance to play Canada in Sunday's Olympic gold medal game.

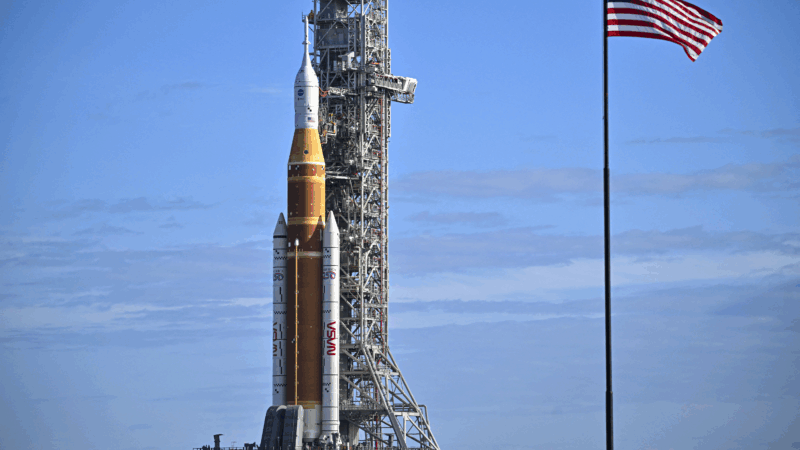

NASA eyes March 6 to launch 4 astronauts to the moon on Artemis II mission

The four astronauts heading to the moon for the lunar fly-by are the first humans to venture there since 1972. The ten-day mission will travel more than 600,000 miles.

Skis? Check. Poles? Check. Knitting needles? Naturally

A number of Olympic athletes have turned to knitting during the heat of the Games, including Ben Ogden, who this week became the most decorated American male Olympic cross-country skier.