Tornado’s swift arrival in Rolling Fork highlights Gulf South’s emergency management needs

Debris left over from a tornado that ripped through Rolling Fork, Mississippi is scattered on the property of the Pinkins family on March 31, 2023. The Pinkins have lived in Rolling Fork for more than 100 years. The deadly tornado that touched down on March 24, 2023, leveled 13 of the family’s homes.

After a string of deadly tornadoes cut through Mississippi nearly a month ago, the community of Rolling Fork is still grappling with how to rebuild. But for some residents, like Josalyn Matthews, the struggle is mental as well as physical.

At a recent town hall, held in the South Delta Elementary School gym, Matthews shared how the storm caught her, like many Rolling Fork residents, by surprise with no advance warning. She also described the lasting, traumatic effect the storm has had on some of her kids, like her daughter — who worries about the tornadoes coming back.

“Now, every day she checks the weather,” Matthews said.

Matthews had just made it home from an evening trip to the nearby Family Dollar on March 24 when the storm roared through her neighborhood. At first, it was calm, but that soon changed.

“All of a sudden it got quiet — like everything stopped. We go in the house and we hear, like, a train sound,” Matthews said.

The tornado touched down sometime after 8 p.m. In the minutes before and during the storm, Matthews said she had no cell service, so she didn’t get the text messages and calls from friends and family warning her.

She also didn’t hear the outdoor siren her town normally turns on during severe weather, but because everything happened so fast, she thinks the sirens wouldn’t have been much help.

“The way this tornado hit, that siren wasn’t going to do any good,“ Matthews said. “They don’t even put it out there where it’s 30 minutes before. It’s probably like when the weather has hit the town.”

Storm notification issues like this are common in marginalized communities like Rolling Fork, a small, majority-Black town in the Mississippi Delta. A Washington Post article reported that Rolling Fork residents and officials questioned if the sirens went off at all. There, the Sharkey County Sheriff’s Office is in charge of the siren system.

Chauncia Willis, the co-founder of the Institute for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Management (I-DIEM), agreed that the timeframe to warn someone of an incoming tornado is short — usually about 13 minutes or less. That means a lot of emergency planning has to happen before a storm occurs.

The problem is that rural and lower-income areas often don’t have the resources and access they need to be prepared for severe disasters. Willis said that stems from a lack of government funding.

“If you are, unfortunately, not prioritized by the local government, then it doesn’t really matter what disaster it is,” Willis, who spent decades as an emergency manager, said. “There will still be a disproportionate impact.”

Rural communities can also face the challenge of having limited professional emergency managers, said Curtis Brown, a visiting senior practitioner in residence at the Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs at Virginia Commonwealth University and Willis’ I-DIEM co-founder.

Some areas only have one professional emergency manager, and Brown said it’s not uncommon for them to “wear multiple hats” to serve their community.

“Investing in more emergency management personnel is really important,” Brown said. “We need full-time, professionally trained emergency managers and staff to really focus attention on preparedness, mitigation, enhancing response and recovery in our community.”

There are some existing warning systems for storms in use, such as local TV stations broadcasting watches and warnings, the National Weather Service reaching people via mobile alerts, its weather radio and online updates and some communities have the aforementioned outdoor sirens.

But Brown said no single method will reach everyone.

“You really don’t want to put all your eggs in one basket,” Brown said. “Technology is great, but, we’ve seen where technology fails. There has to be different modes of communication and outreach.”

There’s no blanket solution for creating an emergency response plan that will work for every community, but Willis said there are some key objectives. The first step is identifying the most underserved or vulnerable communities, where year-round training and planning for how to respond to natural disasters is necessary.

During her time as an emergency manager, Willis provided mobile home residents with weather radios since mobile homes are more likely to sustain damage during severe weather events. The radios are important for making sure these residents, especially, get alerts for often late night storms. Expanding broadband access to get weather alerts to more people would also help, but Brown said more old-school ways of getting information out might actually be more effective for some marginalized communities.

He encouraged community-based organizations to play a role, citing an example of a group in Florida that would go door-to-door assisting people with evacuations or preparedness measures prior to a hurricane.

As the Gulf South experiences more frequent extreme weather events, the need to invest in emergency pre-planning is growing. In 2022, Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana ranked among the top 10 states with the most recorded number of tornadoes, according to the Insurance Information Institute.

“We typically have been used to these Midwestern outbreaks of tornadoes,” Brown said. “We probably need to consider more safe room investments in terms of grants and funding further to the east and to the southeast.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Camp Mystic parents from Alabama seek stronger camp regulations

Sarah Marsh of Birmingham, Ala. was one of 27 Camp Mystic campers and counselors swept to their deaths when floodwaters engulfed cabins at the Texas camp on July 4, 2025. Sarah’s parents are urging lawmakers in Alabama and elsewhere to tighten regulations.

Court rebuffs plea from domestic workers for better pay and respect

They're often paid low wages and lack job protections. A petition to the country's supreme court to support their demands did not see success — and they are protesting.

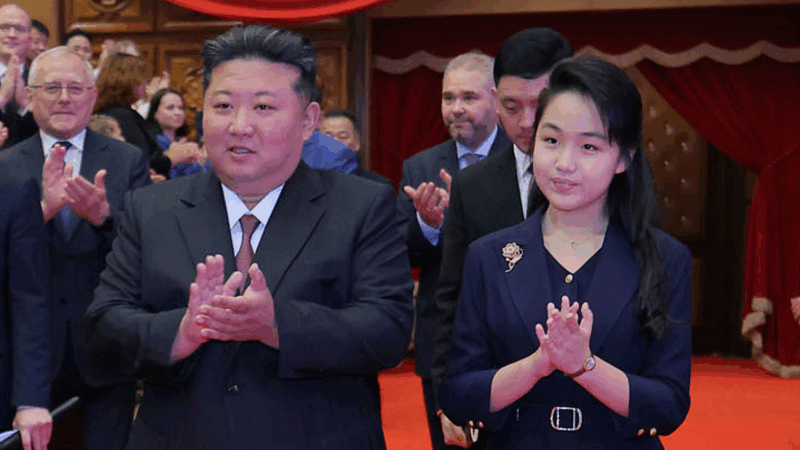

Spy agency says Kim Jong Un’s daughter is close to be North Korea’s future leader

Seoul's assessment comes as North Korea is preparing to hold its biggest political conference later this month, where Kim is expected to outline his major policy goals for the next five years.

Using GLP-1s to maintain a normal weight? There are benefits and risks

Drugs like Zepbound and Wegovy are intended for people who are overweight. Some patients are using them after bariatric surgery to keep pounds from creeping back. Others may just want to lose a few pounds.

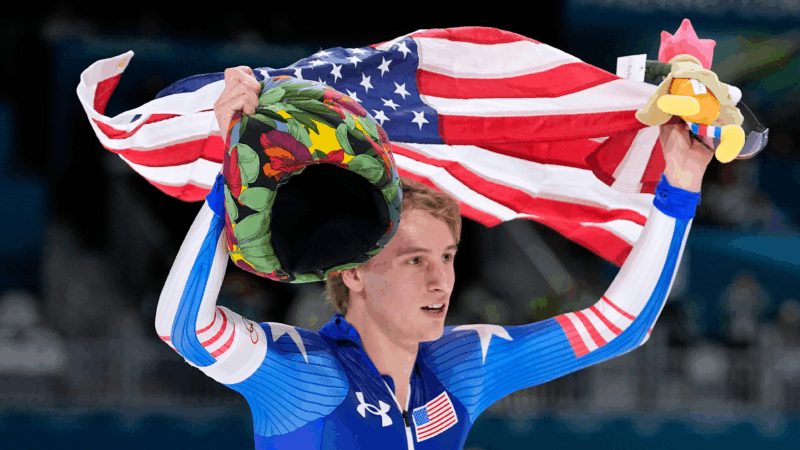

Jordan Stolz opens his bid for 4 golds by winning the 1,000 meters in speedskating

Stolz received his gold for winning the men's 1,000 meters at the Milan Cortina Games in an Olympic-record time thanks to a blistering closing stretch. Now Stolz will hope to add to his collection of trophies.

Free speech lawsuits mount after Charlie Kirk assassination

Months after the killing of Charlie Kirk, a growing number of lawsuits by people claim they were illegally punished, fired and even arrested for making negative comments about Kirk.