She looked for help after her power bill doubled. But aid for utilities often falls short

This story is part of a crowdsourced project investigating utility billing issues in Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi. Do you have a utility bill that you’d like us to look into? Submit it here, and with your permission, we may use it in one of our monthly features.

Dolabriel Curry-Hurst doesn’t believe in handouts.

That’s part of the reason she started farming on her land in Duncanville, Alabama — a rural spot an hour southwest of Birmingham. It’s a small operation with a few chickens and pigs. But Curry-Hurst wanted to teach her kids a lesson in self-sufficiency.

“Just the idea they see us going to get eggs every day is leaving the impression that I don’t have to go to Walmart,” Dolabriel Curry-Hurst said. “You can go buy a chicken.”

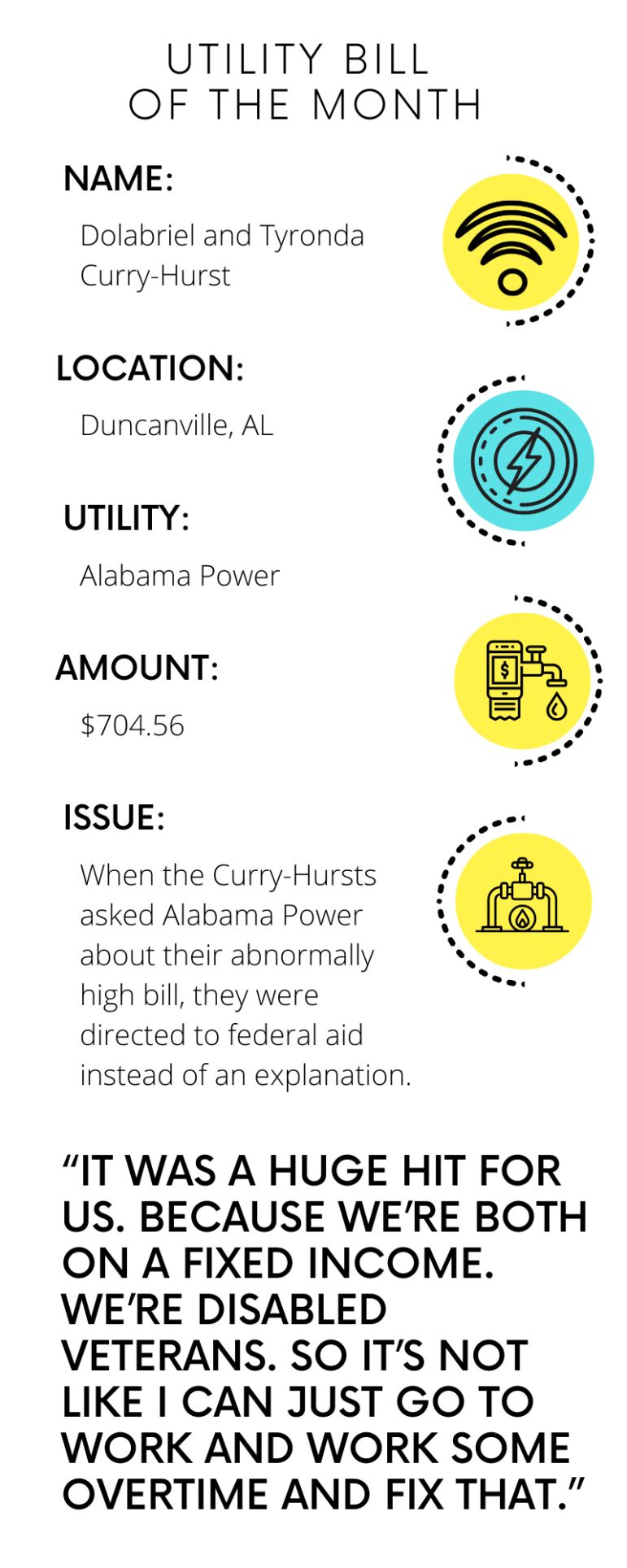

But when her power bill doubled in January, jumping to more than $700, she had to learn a different lesson: Where do you turn to for help when your power bill skyrockets?

About one out of every three people in the South struggles to pay their power bills, according to the Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance (SEEA). The good news is that help exists — the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP). Experts praise it for providing financial assistance to cover energy bills.

The bad news — the program doesn’t have nearly enough money to cover everyone who needs it. Only about 12% of eligible families in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana received LIHEAP help in 2021.

“The scale of the problem is huge and the scale of the funding that is being deployed to address the problem is not,” said William Bryan, director of research at SEEA.

Asking what’s behind the bill

Curry-Hurst’s first instinct was to ignore the more than $700 bill. Her therapist told her otherwise.

“She was like OK, don’t cry about it. Call Alabama Power,’” Dolabriel Curry-Hurst said.

The hope was for Alabama Power to help her understand the reason for the big expense, which Dolabriel Curry-Hurst called a huge financial hit. The family hadn’t changed anything with their lifestyle to explain the jump. If she talked to the company, maybe she’d find out about an appliance that drew too much power, or that someone was illegally siphoning their electricity.

But when she called Alabama Power, instead of looking for the cause, the representative told Curry-Hurst to check out her local Community Action group to get financial help. These types of agencies can be private or public and are usually local. They help distribute different aid programs — in this case, LIHEAP.

But Curry-Hurst’s wife, Tyronda, was not satisfied with Alabama Power’s response.

“I didn’t ask you for your help to pay the bill,” Tyronda Curry-Hurst said about Alabama Power. “I said ‘Why is my bill this high?’”

Tyronda said Alabama Power did not look into the cause of her high bill and stuck with its suggestion the family turn to Community Action. The utility said when customers call, a customer service representative can walk through the possible reasons behind the high bill, such as weather or increased usage.

“Alabama Power works with agencies across the state for payment assistance programs,” Anthony Cook, a spokesperson for the company said in an email.

When asked how the company determines who’s at fault for the high bill — either something on the customer’s end or equipment Alabama Power is responsible for maintaining — Cook did not directly answer the question, instead saying those are determined on a case-by-case basis. Cook encouraged customers to call the customer service team at 1-800-245-2244 with billing questions.

Curry-Hurst made the drive to the Community Service Programs of West Alabama in Tuscaloosa to have a face-to-face conversation. But when she got there, she was told the program was out of funds.

Praised aid, just not enough

The federal government started aiding low-income households with their power bills back in 1975. The programs went with different details and names through the years before landing on LIHEAP in 1981. Families can receive hundreds of dollars in aid to partially cover cooling or heating costs, depending on guidelines that states set for themselves and other factors, like household size and income.

Affordable energy advocates have pointed to LIHEAP alongside the Weatherization Assistance Program — which pays for making homes more energy efficient — as the essential framework for dealing with energy insecurity.

“As long as there’s poverty in this country, we’re going to need programs such as LIHEAP to provide relief to struggling families,” said Maria Castillo, a senior associate on Rocky Mountain Institute’s (RMI) carbon-free electricity team.

According to the RMI, Congress would have to increase funding “10 to 20 times above 2021 levels” to fully support every eligible household — usually families not making more than 150% of the federal poverty level.

That’s a tough sell for politicians looking to cut spending. But when low-income families can’t pay their power bills and get disconnected, those costs get passed on in the form of higher rates to other energy customers.

“The thing about utility bills is they get paid one way or another,” said Joe Daniel, manager of RMI’s carbon-free electricity team. “It’s a matter of whether it comes at the cost of somebody being disconnected. At the cost of someone choosing to not eat food… or whether we give them the funds directly so they can pay it themselves and prevent those outcomes.”

Help instead of answers

The Biden Administration added more than $1.5 billion in LIHEAP funding this year and the program received big cash injections throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Because of that, the Community Service Programs of West Alabama said they haven’t run out of funds in years. So, it’s not clear why Curry-Hurst was told the group had no money left to help her.

When contacted by the Gulf States Newsroom to ask why Curry-Hurst was turned away, a director said that shouldn’t have happened and they would reach out to her directly.

“I’ve been here since the onset of COVID. We’ve had funding and that’s never a reason for us to turn you away,” said Stacey Taggart Cotton, director of supportive services for the Community Service Programs of West Alabama.

Dolabriel Curry-Hurst did eventually receive $200 in assistance from a veteran’s group to help pay for that expensive January bill, though never an explanation for the price. Now, she’s worried about what will happen if another high electric expense comes in the winter. She called the last one a huge hit.

“We’re disabled veterans. It’s not like I can just go to work and work some overtime,” Curry-Hurst said. “We’re not going to be able to do that again.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Here’s how world leaders are reacting to the US-Israel strikes on Iran

Several leaders voiced support for the operation – but most, including those who stopped short of condemning it, called for restraint moving forward.

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.

Why is the U.S. attacking Iran? Six things to know

The U.S. and Israel launched military strikes in Iran, targeting Khamenei and the Iranian president. "Operation Epic Fury" will be "massive and ongoing," President Trump said Saturday morning.

Sen. Tim Kaine calls on the Senate to vote on the war powers resolution

NPR's Scott Simon talks to Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., about the U.S. strikes on Iran.

Iran strikes were launched without approval from Congress, deeply dividing lawmakers

Top lawmakers were notified about the operation shortly before it was launched, but the White House did not seek authorization from Congress to carry out the strikes.

Political science expert weighs in on Iran’s nuclear program in light of U.S. strikes

NPR's Scott Simon speaks to Ariane Tabatabai, the Public Service Fellow at Lawfare, about U.S. attacks on Iran and how President Trump's calls for regime change might be received there.