Seeking asylum in the U.S. is not easy. It’s harder when you speak a rare language

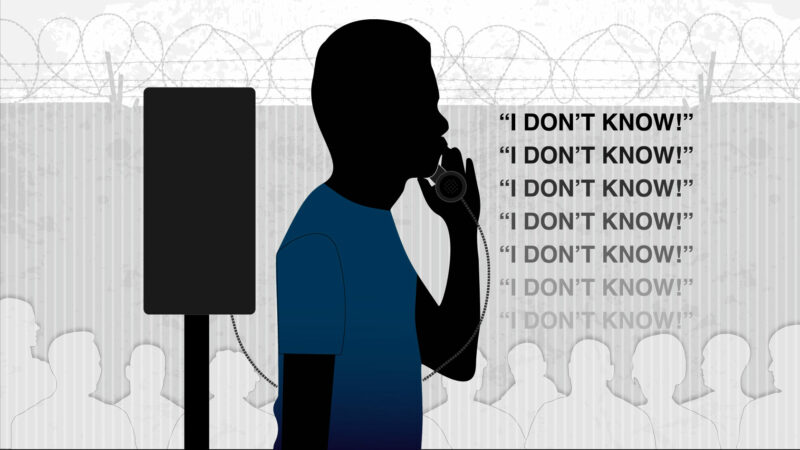

In an interview with an asylum officer, Hammadou answered questions with “I don’t know,” nine times due to a language barrier, according to his attorney.

By the time asylum seekers Moussa and Hammadou were released from detention centers, they had been living in the former private prisons in Mississippi and Louisiana for nearly eight months.

For most of that time, the two men from Burkina Faso in West Africa feared deportation. Going back home for both men was not an option. They both fled Burkina Faso after being attacked and left for dead by armed men — most likely belonging to one of the transnational extremist groups, including Al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates, that have terrorized their home country since 2015.

Asylum officers, however, ruled that their claims of fear of experiencing torture or persecution if they were returned home were not credible. Mich Gonzalez, an attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center who is representing the two men, believes the miscommunication led to their denial.

When immigrants come to the U.S. seeking asylum, they go through what’s called a credible fear interview to determine if they will be allowed to apply for protection and stay in the country. For those who speak less common languages, getting this interview in their native tongue can be a challenge, resulting in delays that cause asylum seekers to languish in detention centers.

After trying and failing to get their interviews in Bissa, both Moussa and Hammadou said they were interviewed by asylum officers in French, a language neither of them is fluent in. We are using pseudonyms for both men because they fear that revealing their identity could affect his asylum case.

French is the official language of Burkina Faso, a former French colony, but both men, like more than 1.5 million people in West Africa, speak Bissa.

“I think there’s something especially cruel about forcing people to be interviewed in the language of their country’s colonizers,” Gonzalez said.

Asylum seekers and rare languages

United States Citizenship and Immigration Systems, the agency responsible for processing permanent residency, citizenship and naturalization, developed a procedure for dealing with rare language speakers when a scarcity of interpreters of Pakistani Pashtu and some Guatemalan indigenous languages was leading to major delays in processing credible fear screenings.

According to a 2013 memo, when asylum seekers declare that their preferred language is a rare language, an interview must be scheduled to determine if they are comfortable with another more common language. However, if the asylum officer conducting the interview determines that the asylum seeker is unable to communicate in the other language, an interpreter should be found within 48 hours of the initial interview.

USCIS 2013 Rare Language Memo by orlando_flores_jr on Scribd

The USCIS policy states that if no interpreter can be found in the preferred language in a reasonable amount of time, the asylum officer should issue them a Notice To Appear, which allows them to skip the credible fear screening process and make their claim for asylum in front of an immigration judge. Asylum seekers can bring their own interpreters to these hearings and the court hires monitors to ensure the interpreter is communicating accurately.

A representative from USCIS confirmed that this is the agency’s policy. According to Gonzalez, officers from the Houston Asylum Office, which conducts credible fear interviews for immigrants detained in Mississippi and Louisiana, did not follow USCIS procedure.

“There is a memo. It has not been rolled back, it has not been rescinded,” Gonzalez said. “I asked them, ‘Can you please just issue a Notice To Appear for these two men? It appears you failed to adhere to your own policy.’”

When asked about cases like Hammadou and Moussa’s, a USCIS representative said the agency, “cannot speak to a specific case or speak in hypotheticals,” and noted that asylum seekers can seek a review of the negative credible fear determination from an immigration judge. But a recent analysis of immigration court data by the Human Rights Center Investigations Lab found that judges almost always affirm asylum officers’ negative credible fear findings.

Fleeing Burkina Faso

Hammadou said if he had been able to speak with an asylum officer in Bissa, he would have been able to explain the attack the extremists carried out on his village that caused him to flee.

Hammadou said he and some of his friends were gathered in a market talking to each other when they heard the gunshots. The armed men took Hammadou and six others into a nearby bush where they shot four of the men. The attackers then beat the other three, including Hammadou, with the butt of their guns.

“When they got in our village, they started killing women, kids, everybody. They just started shooting,” Hammadou said, speaking through a volunteer interpreter.

Hammadou believes the men thought he was dead when they left him there. He was picked up by a stranger who he says carried him to a nearby village where he regained consciousness and made his decision to flee. He never returned home.

Moussa said he was working as a gold miner in a village near Fada N’Gourma, a major city in eastern Burkina Faso, when the terrorists came and began attacking people with machetes. He said the armed men tried to recruit him to join them in traveling from village to village, killing people, burning homes and capturing livestock. When he refused, they beat him and five other men, cutting him several times with the machetes.

He says the scars from the attack are still visible all over his body.

“My whole body was bloody,” Moussa said. “I was just laying there like nothing. They picked me up and threw me in the bush and they left me there.”

Moussa was also taken to a nearby village by a group of women who found him. Once he was strong enough to travel, he fled to neighboring Togo and then to Brazil, where he says security was an issue. He stopped in cities in Peru, Ecuador and Colombia, begging to receive enough money to keep traveling toward safety with no destination in mind.

On his journey, he followed groups of other travelers from Haiti, Venezuela and other countries experiencing conflict. By foot, he crossed the notorious Darién Gap, between Colombia and Panama, where he says he and the people he was traveling with were robbed of their clothes, food and shoes.

“We had to walk with bare feet,” Moussa said. “When I got to Panama I couldn’t even walk.”

What is a credible fear interview?

Eventually, Moussa and Hammadou crossed into the U.S. via the Texas-Mexico border in April 2021 and declared to Customs and Border Patrol agents that they intended to seek asylum. They were processed and then, as is protocol, they were sent to a detention facility where they would go through their credible fear interviews.

“It’s supposed to be a low threshold finding that your fear is credible,” Gonzalez said. “Essentially, you just have to be believed and you just have to show that you’re afraid of something that would generally fall into the category of asylum.”

When asylum applicants go before a judge they must prove that they belong to a particular persecuted group — such as the LGBTQ community — or that they are fleeing persecution based on race, religion, nationality or political opinion. The credible fear interview also screens for people who qualify for protection under the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment — an international human rights treaty.

Gonzalez believes that the harm his clients faced met those requirements, but they were denied. The issue, Gonzalez believes, is rooted in both men’s inability to clearly communicate the harm they endured. Moussa and Hammadou mostly told the French interpreters who assisted in their interviews, “I don’t understand,” when presented with a question.

“[Hammadou] answered, ‘I don’t know,’ approximately nine times during his credible fear interview,” Gonzalez said, “which to me would indicate maybe this man does not understand what the interpreter is saying.”

‘I told them that I don’t speak French’

Moussa and Hammadou were both offered credible fear interviews in French multiple times. Hammadou said he was called from his dorm in Adams County Correctional Center in Natchez, Mississippi — where most of these interviews in the New Orleans ICE Field Office region are conducted — to a room with telephones three times before he finally shared his story with an asylum officer.

Each time, when asked what language he preferred to be interviewed in, he answered Bissa. Each time, however, he was sent back to his dorm because the asylum office could not find a Bissa interpreter.

For weeks he watched as people who completed their credible fear interviews left the facility. (He didn’t know that some of them were being transferred to other detention centers.)

“I thought that it was the way to be released because when somebody gets the interview done, they’re no longer staying there,” Hammadou said. “So at some point, I felt compelled to do the interview in French. I thought it might be an opportunity for me to be released.”

The fourth time he was called to be interviewed, Hammadou chose to go through it in French. Communication was difficult.

“Since I don’t speak French, there were some words that I didn’t understand,” he said. “I didn’t understand what the word ‘torture’ means in French. I understood that word later on so in the questions they’ll ask you, ‘Have you been tortured?’ and you’re like, ‘No.’

“It was a ‘Yes’ question and I said, ‘No.’ Those kinds of things happened a lot.”

Other mistakes plagued Hammadou’s credible fear interview, including his reference saying he is from “Burki, Burkina Faso,” a place that doesn’t exist.

Similarly, Moussa was called for his interview three times. During his third attempt, he was told he had no choice but to go through the interview in French.

“I told them that I don’t speak French, I didn’t go to school,” Moussa said.

Both men received a negative credible fear determination, meaning they didn’t prove that their fear of persecution or torture if they were returned to Burkina Faso was believable, despite the many international news reports documenting terrorism in the country. In January, the country’s president, Roche Kaboré, was overthrown in a military coup for his mishandling of extremist violence.

Gonzalez wondered why his clients weren’t allowed to appear before an immigration judge once asylum officers realized they could not find Bissa interpreters. He wrote the asylum office several times, asking officials to review and reconsider the original negative credible fear determinations. Each time he received a boilerplate response affirming the initial decision.

While Gonzalez was pleading their cases, the men were transferred to Winn Correctional Center, another former private prison owned by LaSalle Corrections in Winnfield, Louisiana. They described their lengthy stay in detention as disheartening.

“The time I spent in prison kind of messed up my brain,” Hammadou said. “The time I was spending there was actually wearing me out.”

Moussa described Winn as a place where “you just eat to be alive, not to be filled up,” and where the communal dorm was cramped.

‘Now, I breathe a different air’

Gonzalez eventually secured their release using a class action lawsuit, Fraihat v. ICE and DHS, which challenged the agency’s ability to provide proper medical and mental health care to detainees. Gonzalez said he noticed that Hammadou and Moussa were becoming severely depressed and exhibiting symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder while in detention.

The two men posed no security risk and had no criminal records in the U.S. or in Burkina Faso, which bolstered the argument that they should be released. Given that they had spent more than six months in detention, they were eligible to apply for Habeas Corpus to secure a court-ordered release.

Both men were released to sponsors — people who claim financial responsibility for immigrants while they complete their immigration processes — in other parts of the country. They had to wear ankle monitors before they were let out of detention in Louisiana. Hammadou is living with his sponsor in the midwest and Moussa is living on the East Coast.

The journey to asylum for them is far from over. It’s been nearly one year since they each arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border and they are still waiting to see if they will get the protection they desperately want.

Both men have appealed to the regional asylum offices where they live now to review the credible fear determinations they received from the Houston Asylum Office. Hammadou was finally issued a notice to appear before an immigration judge. His court date is set for September 2023 — more than a year and a half after it was issued. Moussa’s credible fear determination is under review.

“I am very happy now since I am out of prison,” Moussa said. “I’m living a better life. Now, I breathe a different air.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration among Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama and WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly identified U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Deadline looms as Anthropic rejects Pentagon demands it remove AI safeguards

The Defense Department has been feuding with Anthropic over military uses of its artificial intelligence tools. At stake are hundreds of millions of dollars in contracts and access to some of the most advanced AI on the planet.

Pakistan’s defense minister says that there is now ‘open war’ with Afghanistan after latest strikes

Pakistan's defense minister said that his country ran out of "patience" and considers that there is now an "open war" with Afghanistan, after both countries launched strikes following an Afghan cross-border attack.

Hillary Clinton calls House Oversight questioning ‘repetitive’ in 6 hour deposition

In more than seven hours behind closed doors, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton answered questions from the House Oversight Committee as it investigates Jeffrey Epstein.

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.

Trump’s ballroom project can continue for now, court says

A US District Judge denied a preservation group's effort to put a pause on construction