How will Avis Williams lead New Orleans Public Schools? Look to her work in Selma

Selma superintendent Avis Williams meets with a small group of students during “lunch and learn” at Edgewood Elementary, May 9, 2022.

Avis Williams always knew she wanted to be a teacher when she grew up, but the biggest obstacle in the way of her dream was figuring out a path to reach her goal.

As a student, Williams shined, winning numerous college scholarships that would have helped turn her dream into a reality. But the process of applying and going off to school was daunting as a first-generation four-year college student. No one at her school intervened, so Williams joined the U.S. Army instead.

Fast forward more than three decades later and Williams, 52, is now the one doing the intervening for others.

After four years in the army, she worked as a fitness instructor, co-owned a gym and eventually put herself through college — earning a bachelor’s degree from Athens State College, master’s degrees from Alabama A&M and Jacksonville State universities and a doctorate and education specialist degree from the University of Alabama. She exceeded her dream of becoming a teacher, later becoming a principal and now a superintendent. As a Black woman, Williams is a rarity among public school superintendents, the vast majority of whom are white men.

Williams’ guiding principle as a school leader has been to be the support system she was not afforded — making sure that all students know they have options and providing them with the support they need to access them.

A prime example of this can be seen in Williams’ time as superintendent of Selma City Schools in Selma, Alabama. When meeting with students, she asks them two questions; “What are your hopes and dreams?” and “What do you need from your school?”

“I hear their pleas in terms of wanting something different from the poverty that they live in and I can relate because I grew up in poverty,” Williams says. “I know that part of my gift is to be able to not only listen but to support and to act.”

It’s an approach she says she plans to continue when she becomes the superintendent of New Orleans’ public schools in mid-July.

How personal experiences informed learning

It’s easy to draw a throughline from Williams’ personal experience to her priorities as a superintendent. She’s trying to give students and their families something she says is often in short supply in poor, Black communities — hope.

Selma is one of the smallest and poorest cities in Alabama’s Black Belt. The public school system enrolls less than 3,000 kids. More than 98% of the students are Black and 90% are considered low-income.

“We’ve got children and families that have lost hope,” Williams said. “They are living in poverty and their parents and their parents’ parents have lived in poverty and that’s all they know.”

Williams can relate to her students’ experiences. She grew up poor in Salisbury, North Carolina in the 1970s and 80s, the middle child out of five siblings. Her father was verbally abusive and told her she would never amount to anything, which Williams credits as pushing her to work harder.

After she graduated from high school, her mother left her father. He started stalking her and eventually murdered her while Williams was away at Army basic training.

“Throughout my career, I’ve always taken notice of people in trauma or people who have gone through traumatic events,” Williams said. “I’ve gotten help myself and certainly want to represent that yes, there’s trauma, but there’s also resilience and healing.”

Williams doesn’t hide her personal story from her teachers, students or their families. Instead, she says being vulnerable is part of what makes her a good leader. She uses her story to connect with families and motivate her staff.

“When we think about our achievement gap and we think about our poverty levels and we think about the lack of resources, every single one of those situations has faces and names,” Williams told her colleagues when she worked in the public school system in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. “Every one of them can be something, can be anything they want to be. They need somebody to believe in them.”

Williams said she was attracted to New Orleans because while it is a much bigger district — serving roughly 44,000 students compared to the 2,700 in Selma — the two systems and cities have a lot in common.

Along with high rates of poverty, both systems enroll a large number of students who have experienced trauma from gun violence and other violent crimes, dampening many students’ and families’ dreams.

While responding to these painful realities isn’t the direct responsibility of the public school system, Williams said those circumstances can’t be ignored.

“We have to make sure that children are safe, healthy and well before we can expect them to learn,” she said. “I do think the schools have to play an active role simply because we have such a captive audience for such a length of time.”

At the same time, she doesn’t think it should be a classroom teacher’s job to take on these challenges alone. Instead, she said it’s her job as superintendent to make sure there’s a system in place to make sure all students and families can access the support they need.

Earning trust with a willingness to listen

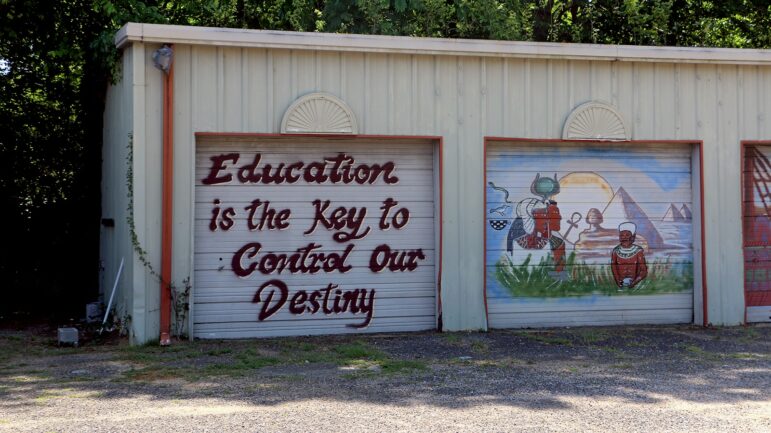

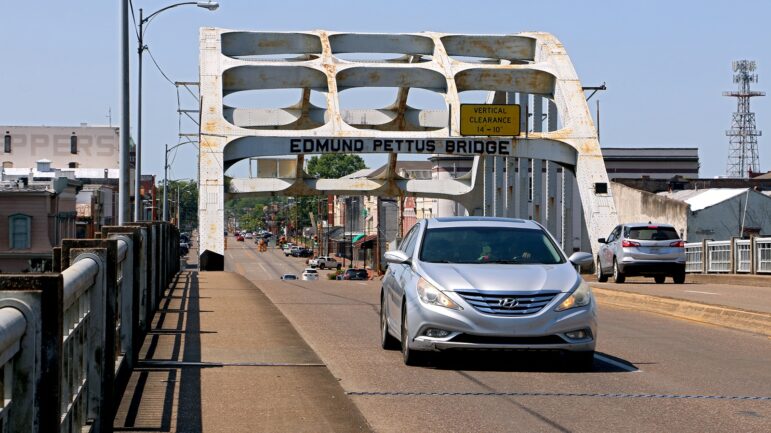

In Downtown Selma, storefronts and warehouses line the waterfront near the historic Edmund Pettus Bridge, where state troopers attacked peaceful civil rights marchers more than 50 years ago.

Columbus Mitchell, a local tour guide and public school parent, stands in the shade talking to a small group of tourists.

He says that while some parents were initially wary of Williams since she wasn’t from Selma, she earned their trust quickly. Similar concerns were made by some parents in New Orleans — Williams and the other two finalists to succeed outgoing superintendent Henderson Lewis Jr. were all chosen from outside of Louisiana — but Mitchell said they have nothing to fear.

“I can assure the people there in Louisiana that they’re getting someone that’s really going to work hard for them and someone that really knows what it’s like to connect with people,” he said.

Williams said she didn’t come to Selma with any “big ideas,” just a willingness to listen to the community and work with them to improve the school system.

Across town, people have nothing but nice things to say about the outgoing superintendent, who has become a fixture in the community. She attends church, shops locally and is a member of Selma’s Rotary Club.

She’s also an avid runner — her car’s custom license plate says “RUNR” — and can often be spotted around town training for countless fun runs and half marathons.

“I run in this community. I get horns blown at me,” she said. “Sometimes people stop and say ‘Hey Miss Superintendent …’ And I’m like ‘Can you call me Monday?’”

One teacher says the thoughtful emails Williams sends daily inspire her. Another says she’s the reason a water-damaged library was finally restored. They’re excited about her new job in New Orleans but sad to see her go.

“She will be missed… because she made herself visible and available to actually work in our community,” said Krystal Dozier, the librarian at Selma’s Edgewood Elementary. “I’m definitely going to miss seeing her run up and down the streets of Selma.”

Johnny Moss, Selma’s school board president, said while he wishes the district could have held onto Williams for longer he’s grateful for the time she’s spent in Selma.

“I told her, ‘We’re excited for you,’” Moss said. “‘That helps us recruit because the next superintendent knows that, hey, you do a great job here, you could move on to other, bigger and better things.’”

Leading with ‘excellence, equity and joy’

When Williams arrived five years ago, the district had a bad reputation and was under the shadow of state intervention.

Under her leadership, graduation rates and test scores have both increased. Today, the city’s schools are celebrated for their attention to mental health, focus on restorative justice and high-quality academics.

“I live by my core values, which are excellence, equity and joy,” Williams said. “The work that I do will speak for itself, but I also plan to engage and to have those conversations and to make sure that people who need a seat at the table… have a space where their voices are heard.”

Moss said Williams changed the schools’ culture and attracted new teachers to the district with her innovative ideas.

“We needed a culture change,” Moss said. “We needed someone to put joy and fun, who could deal with people and then who had the educational background and the leadership background to make leaders within our system.”

One change Williams brought on was transforming all of Selma’s schools to be STEM-oriented; each with its own niche. Clark Elementary, for example, is described as a “social justice academy,” while Edgewood Elementary is focused on entrepreneurship and commerce.

Another priority for Williams is equity, which she said has to do with both access and rigor.

“We’re not sugarcoating and dumbing [the curriculum] down because our babies are in poverty or because they might be below grade level,” Williams said. “Some of them are two or three grades below grade level and they still deserve access to a rigorous, high-quality education.”

Williams said she’s done her best to match the opportunities provided to students in the state’s more affluent districts, like Hoover, a fast-growing majority-white suburb that’s 90 minutes away.

“What I always say is, ‘If it’s good enough for the children in Hoover, then it’s good enough for my scholars,” Williams said. “What does it take for my scholars to have what they have there?”

The biggest change facing Williams in New Orleans is taking charge of an all-charter school system. Charters are relatively new to Alabama — they were first approved at the state level in 2015 — and Selma doesn’t have any currently.

But despite limited interactions with charter schools throughout her career, Williams’ approach to specialized schools in Selma could be a sign she’s prepared to lead New Orleans’ system.

“I come to you as an instructional leader,” Williams said when asked by WWNO about her prior experience working with charter schools. “I know instruction, curriculum [and] leadership.”

Marytza Gawlik, a researcher at the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teachers, said those are the exact skills a superintendent needs to be successful in a charter system.

“One of the pivots that a charter school superintendent really needs to make is to operate not only as an instructional leader but as a transformational leader,” Gawlik said, since the original mission of charter schools was to “serve as hubs of innovation.”

While innovation is supposed to be the focus of charter schools, that doesn’t mean traditional schools can’t innovate as well.

“Charter schools and traditional schools have a lot to learn from each other,” Gawlik said.

Planting a seed

Edgewood Elementary, a squat brick building, has bumblebee decals everywhere. At a visit in early May, Williams matched the school’s mascot perfectly, wearing a bright yellow dress.

Williams refers to these visits with her students — who she refers to as her “scholars” or her “babies” — as “lunch and learn.” Students eat first — on this day it’s shredded meat, bread, peas and watermelon — then have a conversation with Williams when they’re finished.

She starts by asking if they know what she does at school.

“Do you make sure everything is good?” Elanuah, a third-grader, asks tentatively.

“Yes. I try my best to,” Williams answers.

From there, the conversation shifts to the future. She asks her first question — ‘What are your hopes and dreams?” — and the students all readily share their answers

One student says he wants to be a veterinarian; another a professional baseball player. Caleb, a kindergartener, answers the question by drawing a picture of himself flying through the sky. Williams gently asks whether he wants to fly in a plane or use a parachute.

“Both,” he replies confidently.

Elanuah chimes in and says when she grows up she wants to become a dancer and move to L.A.

“Lower Alabama?” Williams jokes. “Oh, you mean the other L.A. — Los Angeles.”

But while Williams laughs easily and pokes fun at the kids, she still takes the conversation seriously.

Elanuah may want to go to college first, she says. She could major in dance or get a fine arts degree so she has a variety of career paths.

It’s unclear how much of the conversation Elanuah is absorbing but Williams is planting a seed.

That’s when Williams returns to her second question; to make those dreams come true, “What do you need from your school?’ Most of the students don’t have an answer yet, but that doesn’t matter. Williams has already accomplished her goal by getting the first of, hopefully, many conversations going.

Before she leaves, she tells them as they chase their dreams, there may be things they’ll want or need. If that happens, they should always feel comfortable asking for more resources, she says.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story misspelled Edgewood Elementary student Elanuah’s name.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration among Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama and WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Pentagon shifts toward maintaining ties to Scouting

Months after NPR reported on the Pentagon's efforts to sever ties with Scouting America, efforts to maintain the partnership have new momentum

Why farmers in California are backing a giant solar farm

Many farmers have had to fallow land as a state law comes into effect limiting their access to water. There's now a push to develop some of that land… into solar farms.

Every business wants your review. What’s with the feedback frenzy?

Customers want to read reviews and businesses need reviews to attract customers. But the constant demand for reviews could be creating a feedback backlash, experts say.

‘Get back to integrity’: Oklahoma’s Kevin Stitt on Republicans after Trump

NPR's Steve Inskeep asks Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt about his spat with President Trump, immigration and the future of the Republican Party.

Civil rights leaders say the racial progress Jesse Jackson fought for is under threat

Activists say racial progress won by the Rev. Jesse Jackson is under threat, as a new generation of leaders works to preserve hard-fought civil rights gains.

Tariffs cost American shoppers. They’re unlikely to get that money back

After the Supreme Court declared the emergency tariffs illegal, the refund process will be messy and will go to businesses first.