Gulf South hospitals face ‘worst-case scenario’ as staffing costs skyrocket

ICU nurse Derek McKenzie finishes helping a critically ill COVID-19 patient at King's Daughters Medical Center in Brookhaven, MS, Jan. 23, 2022.

When Troy Nations woke up from a coma last September, he’d been in the hospital for a month, but he wasn’t in the original bed or the emergency room he had checked into. He was half an hour down the road at King’s Daughters Medical Center, a facility in rural Brookhaven, Mississippi.

Nations, who is in his mid-30s but was unvaccinated at the time, had developed a case of COVID-19 so severe his lungs felt like they would collapse. Time was of the essence, but during the deadly delta surge in the Gulf South, beds were sparse. That’s when King’s Daughters stepped in, finding space to treat him.

“They had double beds in all the emergency rooms, [patients] all on ventilators. All the ICU beds were full. It really looked like a war zone,” Caroline Nations, Troy’s wife, said. “And they were determined to get all their patients well.”

Caroline Nations believes that if her husband hadn’t ended up at the small town hospital, he wouldn’t have survived.

King’s Daughters, a small operation with about 99 beds, is one of the biggest employers in Brookhaven — a sleepy, little city 55 miles south of Jackson with about 12,500 residents. The town is split in half by railroad tracks dotted with small businesses, arcades and mom-and-pop diners.

Most hospitals outside Brookhaven are at least a 30-minute drive away making the facility critical to the community and literally life-saving for patients, like the Nations, from surrounding areas.

But as some states are emerging from the omicron surge, Mississippi hospitals are still in crisis, including King’s Daughters.

The number of people looking for care continues to grow, but hospitals statewide are reducing their bed numbers because there’s no one to staff them. At the same time, an influx of federal money into the travel nurse market is likely driving up the cost of hiring the temporary staff necessary to fill workforce gaps. On top of patient and staffing issues, the bills keep piling up while resources remain limited.

Now, King’s Daughters — like many safety-net institutions in small towns across the country — faces an uncertain future.

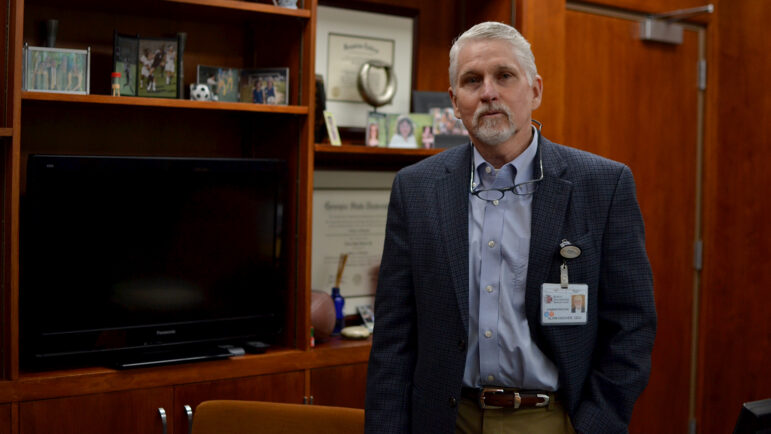

“I’ve been looking at a worst-case scenario, getting worse and worse for two years now,” Alvin Hoover, King’s Daughters Medical Center CEO, said.

Dealing with unprecedented financial pressures

Handling the delta surge was hard enough for King’s Daughters. The omicron variant has furthered that strain, with the hospital operating at a third of its capacity because there is simply not enough staff.

Across the U.S., nurses are either quitting and retiring or getting sick and having to miss work. According to data from staffing agency Aya Healthcare, the number of open staff nursing positions has doubled throughout the pandemic from 100,000 to around 200,000.

“Now the best you can do is sometimes less than the best you would have done before,” Hoover said. “Patients come to the emergency room, they wait and wait because we don’t have a room, we don’t have a nurse or physician ready to see them.”

“It’s frustrating for all of us in healthcare to have resources stretched so thin.”

Hoover says in the nursing department alone, the hospital would likely need to hire around thirty people to get it running smoothly again. However, no one is applying.

“If they come in and say, ‘I quit,’ today, then I don’t necessarily want that nurse back. But you know what, if they come back and say ‘We’d like to work here again,’ we’d hire them,” he said.

Hoover offered small bonuses and even tripled hourly rates for some of his nurses for a limited time.

“Hundreds of thousands of dollars that are spent on overtime, extra pay, retention pay, and unscheduled pay. Over the course of the pandemic, you could say millions of dollars now,” Hoover said.

For this hospital, which typically has an operating margin of one or two million dollars a year, these payments are creating unprecedented financial pressures. He’s gotten some help from the government but isn’t sure how long that will last.

How travel nurses — and how much they’re paid — factor in

Travel nurses have been another issue complicating King’s Daughters, and other hospitals, budget issues.

Demand for travel nurses has soared due to the workforce shortage. Data from Aya Healthcare shows, before the pandemic, hospitals sought to hire about 7,000 travel nurses at any one time. By 2021, they were looking for 28,000 on average.

Rates for these nurses have risen steeply due in part to a huge infusion of federal COVID-19 relief money that most states are using to hire travel nurse help for hospitals. In the Gulf South, Mississippi has spent around $90 million, and Louisiana has spent nearly $250 million.

With hospitals and governments able to pay high prices for a nurse contract, travel nurses can cherry-pick the best deal.

Hoover says much of his staff have left to chase these jobs, so he had no choice but to hire travel nurses. While the hospital usually pays full-time nurses around $25 an hour, he has to pay a travel nurse around five times that rate — amounting to upwards of $5,000 a week instead of the $1,000 he’s used to paying.

Even before the pandemic, it wasn’t easy keeping King’s Daughters’ doors open. Mississippi hospitals get less federal funding than other states due to state leaders declining to expand Medicaid last year. Small hospitals like King’s Daughters also often serve high numbers of uninsured patients and rely on government help to offset the cost of care.

Some hospitals have operating margins so small, there is little room for error. Adding the high cost of travel nurses, additional staff retention bonuses and overtime pay to the mix, “is just unsustainable,” according to Robyn Begley, with the American Hospital Association.

“Some hospitals struggle to break even year after year and are really in a crisis,” Begley said.

In the meantime, Hoover said he’s not worried about the hospital closing down in the short term. There’s been enough government aid to keep it afloat, though he knows the long-term future is uncertain, especially if there’s another surge in COVID-19 cases.

For now, he’s mostly concerned about the facility’s ability to continue helping people like the Nations, who find themselves in desperate need of a hospital bed, when there are none other available.

“This is the way the new health care is going to be for the next three months, the next six months and next year. If this pandemic goes away tomorrow, you’re still going to have trouble transferring patients,” Hoover said. “Health care is changing. We have to figure out how to adapt with it.”

Health care workers hold the power now

At King’s Daughters, the small raise in money has been enough to keep some staff, like nurse Derek McKenzie, happy.

McKenzie has been at the hospital for nine years and understands why quitting to become a travel nurse is tempting. But, he thinks there are also downsides to making the move.

“I’m not saying that they don’t pay me well. I’m just saying I’m not going to make what a travel nurse makes even in Jackson right now,” he said. “But, it’s never a guaranteed full-time thing.”

For McKenzie, King’s Daughters is like family. He would like to be paid more, but he understands this small hospital’s finances are tight. His family also lives here, so it doesn’t make sense to uproot his life.

“I’ve been here since I got out of nursing school. I mean, this has been my home base,” he said. “Everybody I know has been here … I don’t have any desire to try relearning new facilities, new doctors and all of that.”

Jaymie Heard, King’s Daughters ICU manager, said he’s thankful for the staff that are sticking around, but it’s clear the mindset of a lot of workers has already shifted.

“A lot of people used to look for jobs for a career path,” she said. “Now they see that they can bounce within their career and make more money. [The idea of] staying long at places is, I think, a thing of the past.

“People are no longer looking at longevity or retirement. They’re going to the higher bidder.”

Barry Asin, a staffing industry analyst says, the reality of the health care industry now is that workers are calling the shots — not employers — and the choice of whether to stay at a hospital or leave is based on what they want in their lives.

“I think the end result of it will be a needed upward revision of how much nurses get paid,” Asin said. “The tables have turned.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration among Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama and WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Bill would move Alabama to closed primaries

Right now, any Alabama voter can participate in a primary election. Lawmakers in Montgomery took up a bill this week that would change that system.

Why ‘Sinners’ should win best picture (but probably won’t) — and more Oscar predictions

NPR critics share their hopes and predictions for the 2026 Academy Awards, which air on Sunday.

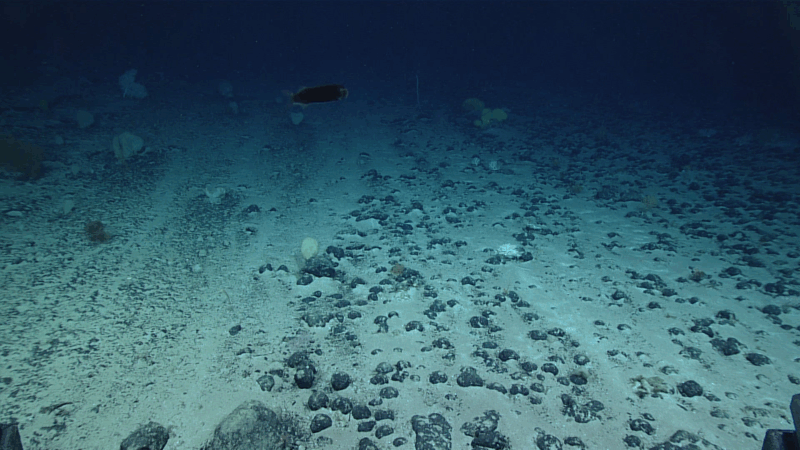

Countries are negotiating rules to mine the deep sea. The U.S. is pushing ahead alone

With growing interest in mining critical metals from the seafloor, countries are now negotiating international rules. The Trump administration is forging ahead on its own, speeding up environmental review for mining the fragile ecosystem.

4 confirmed dead after U.S. military aircraft goes down in Iraq

The U.S. Central Command confirmed that at least four of six crew members on the KC-135 aircraft were dead, after the refueling plane went down in western Iraq on Thursday.

It’s Chalamet vs. ballet in this week’s news quiz. Are your answers en pointe?

Meanwhile, if you've been paying attention to medicine, basketball and the British Parliament, you'll get at least three questions right this week.

Trump wants more apprenticeships. An Arkansas manufacturer is giving it a try

President Trump has touted apprenticeships as part of his promise of a golden era for American workers. But are his administration's investments enough?