Dollar store workers are organizing for a better workplace. Just don’t call it a union.

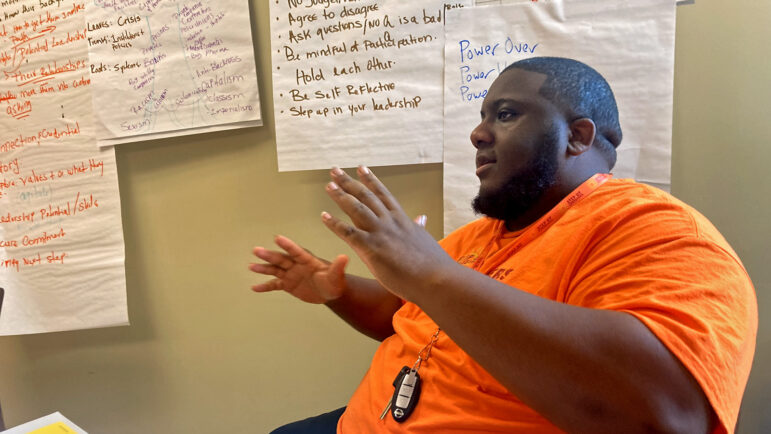

David Williams, a stocker at a Dollar General store, on July 29, 2022, in New Orleans. He’s pushing for better work conditions and pay at his store with help from Step Up Louisiana.

Before David Williams approaches his fellow Dollar General workers in New Orleans to talk about organizing, he knows the first thing they’ll ask: Are you a union?

He answers with a flat no.

“Once the word union is … out the way, that’s when we all get together and come up with a plan and figure out how we [sic] going to fight this,” Williams said.

Dollar stores have expanded across the country and complaints about work conditions and safety have grown with them. Over the past year, workers have been organizing, protesting and striking for better workplaces — fired up by a labor movement that’s led to big union victories at places like Starbucks and Amazon.

But Dollar General workers in Louisiana hope to make change without unionizing. Unions require winning elections and negotiations, which can drag on for years. The word can also be a non-starter when recruiting support, especially in places like the South — a region that’s historically skeptical of unions.

Labor experts say this approach is actually healthy for the labor movement — better to have different groups with separate tactics pushing for workers’ rights than relying just on collective bargaining.

“The flexibility that comes with not being a union is a really valuable tool,” Mary Anne Trasciatti, the director of labor studies at Hofstra University, said.

High cost of cheap prices

Around 2017, Anthony Jackson was attending Southeastern Louisiana University online and found himself in a typical spot for a college student — his financial aid was running low and he needed to find a job.

He found work at a New Orleans Dollar General, enticed by what he believed would be an easy job stocking the shelves and running the cash register. But after being hired, he said he got a “rude awakening.” Beyond the bathroom and air conditioning system rarely working, he said the job was dangerous. One time when he tried to stop someone from shoplifting underwear, the customer lifted his shirt and flashed a gun.

Then there were the rats. Several packages at the store had a foul smell, discoloration and bite marks. Jackson never saw a rodent clearly, but the final straw came when he thought he spotted one out of the corner of his eye darting across the warehouse.

“I was very unhappy,” Jackson said. “That’s what motivated me to get my behind back in school and graduate because I saw as a young person this is not going to be a bright future.”

Other low-wage jobs like McDonald’s have been raising prices to around $15 an hour in response to worker demands and a tight labor market. Dollar stores have also raised wages, but Williams said the one dollar increase he received to $9.25 an hour is not enough.

“It’s pretty much a slap in the face,” Jackson said.

Concerns about safety, rats and low pay have followed dollar stores as they’ve continued growing. Dollar General predicts a net sales growth of 10.5% this year and plans to open 1,100 new stores by the end of its fiscal year.

But among the high profits and skyrocketing stock prices, workers are protesting. Around 100 protesters gathered outside a Dollar General shareholder meeting in Goodlettsville, Tennessee last May.

Most of them came with the organization Step Up Louisiana. Jackson has been training as an organizer with the group, specifically to work with dollar store workers.

Yet the group is careful to clarify that it’s not a union. It has been organizing workers and supporting unions, but doesn’t see unionizing as the best way to improve dollar stores.

“We’re not a union,” Jackson said. “I don’t know if we ever will be but I do know we have momentum right now.”

What’s in a name? Collective bargaining

For as long as there has been a labor movement, there have been plenty of groups pushing for workers’ rights without relying on unionizing.

But unions do have one big advantage over other labor groups — collective bargaining. Once unions agree to unionize, employers are required by law to negotiate with the union in good faith. But getting to that point means winning an election, which can take years, and wiggle room in good faith negotiations can drag the process out even longer.

Some labor experts believe the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, which put legal protections around collective bargaining, led to the labor movement relying too much on unionizing.

“The labor movement is becoming more eclectic again,” Cedric de Leon, a professor of sociology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst’s Labor Center, said.

Alt-labor groups can rely on other tactics including petitions, pressuring politicians and protesting — like the demonstration outside Dollar General shareholder meeting.

They can also go directly to the media to advocate for change. Kenya Slaughter, an assistant manager at a Dollar General store in Alexandria, Louisiana, did just that.

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Step-Up Louisiana helped Slaughter get in touch with the New York Times, which published an opinion piece she wrote. In it, Slaughter called out Dollar General for not providing protective equipment, such as masks and plexiglass. Shortly after Slaughter’s story was published, Dollar General sent equipment to stores.

“(I) did not need a union to get that done and it got gone expeditiously,” Slaughter said. “I had all types of people calling my phone trying to see what they can do.”

Higher-ups at the company started calling Slaughter and she had a list of demands ready for them. Since that 2020 opinion piece, that list has remained mostly unaddressed, but she’s still optimistic her advocacy with Step Up Louisiana will help bring those changes.

Slaughter’s also far from anti-union — like Step Up Louisiana, she supports unions. But for her, a union is a tool, not an end goal.

“Ultimately, I just want what’s right,” Slaughter said. “I want workers making at least $15 an hour coming in.”

The ‘u-word’

When Anthony Jackson approaches dollar store workers, they visibly relax with the “u-word” out the way. Instead, he calls Step Up Louisiana an organization.

Really, though, the biggest difference between the two comes down to semantics.

“[It’s a] play on words, to be honest,” Jackson said. “Because we don’t know people’s assumptions of what a union may be.”

Union can be a dirty word in the South, bringing along connotations of corruption and union dues going into the pockets of higher-ups rather than helping members. Being a union doesn’t prevent a group from using the same tactics as other organizations, but it does come with a negative reputation in some circles that many groups would rather just avoid.

Perceptions of unions have been growing more positive across the U.S., with the number of union election petitions spiking up in 2022 — bolstered by historic union victories at Starbucks and Amazon.

But union membership last year tied for a record low, with even lower numbers in Southern states. Most states have Right-to-Work laws, which means even if a union represents a workplace, the workers do not have to pay union dues. These laws are especially common in the South.

While some groups have been trying to unionize dollar store workers, others, like Step Up Louisiana, feel it's best to avoid the union label due to the legal, financial and cultural hurdles around unionizing. But Wade Rathke, chief organizer for ACORN International, said in workers’ minds, when they’re acting together it’s still technically a union.

During his time organizing domestic workers in New Orleans in the late 1970s, Rathke said his group was careful about calling themselves an organizing committee and telling workers they weren’t a union. But when making a complaint to the local Department of Labor office about not receiving a minimum wage, one of the first things the workers said to the officials was, “we’re here with the union.”

“Association, union, organizing committee — workers know it’s a union,” Rathke said.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration among Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama and WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

When a horse whinnies, there’s more than meets the ear

A new study finds that horse whinnies are made of both a high and a low frequency, generated by different parts of the vocal tract. The two-tone sound may help horses convey more complex information.

Trump’s many tariff tools mean consumer prices won’t go down, analysts say

The Supreme Court struck down President Trump's signature tariffs. But the president has other tariff tools, and consumers shouldn't expect cheaper prices anytime soon, economists say.

Hundreds of American nurses choose Canada over the U.S. under Trump

More than 1,000 American nurses have successfully applied for licensure in British Columbia since April, a massive increase over prior years.

Tax credits for solar panels are available, but the catch is you can’t own them

Rooftop solar installers are steering customers toward leases instead of purchases. Federal tax credits for purchased systems have ended but are still available for leased ones.

5 takeaways from Trump’s State of the Union address

President Trump hit familiar notes on immigration and culture in his speech Tuesday night, but he largely underplayed the economic problems that voters say they are most concerned about.

China restricts exports to 40 Japanese entities with ties to military

China on Tuesday restricted exports to 40 Japanese entities it says are contributing to Japan's "remilitarization," in the latest escalation of tensions with Tokyo.