As Gulf South lawmakers fight over Medicaid, new moms weigh in: ‘Safety nets do save lives’

Tens of thousands of new mothers in Mississippi and Alabama could suddenly lose their health care coverage unless state legislators take action in the coming days.

Unlike 39 other states, Mississippi and Alabama have not opted to expand Medicaid to more people. Pregnant women, however, have always been eligible to get Medicaid, even in non-expansion states.

Recently, anyone able to enroll in Medicaid could not lose coverage as long as the federal COVID-19 public health emergency was in effect. But as early as April 16, the emergency status could end, reverting both states back to their previous coverage period of up to 60 days after giving birth.

Lawmakers in Mississippi and Alabama on both sides of the aisle agree extending postpartum Medicaid coverage to a full year could address some of the reasons why around 700 new mothers die annually in the U.S. – the vast majority of whom are Black and indigenous.

But while the states are similar politically, they’re taking different approaches to address the problem.

Political games at the Mississippi State Capitol

Senate Bill 2033 seemed destined to pass in Mississippi.

The bill, which would have extended Medicaid coverage for pregnant women to a full year after birth, had a groundswell of bipartisan support at the state capitol — being sponsored by both state Democrats and Republicans. It also received full support from the Senate and the House Medicaid Committee when it was introduced before the state House of Representatives on March 9.

The legislation, however, hit a roadblock in the form of Mississippi Speaker of the House Phillip Gunn. In a shocking move, Gunn and House Medicaid Committee Chairman Joey Hood killed the bill, by choosing to not bring it up for a vote.

“We’ve been very clear we’re just not for Medicaid expansion,” Gunn said in the halls of the capitol. “This is arguably Medicaid expansion, certainly expanding coverage.”

In a rebuttal, Republican Sen. Kevin Blackwell, principal author of the bill, said an extension is not expansion.

“Not one additional enrollee will be added by extending this. These are ladies who have already qualified. All we’re doing is extending that benefit for another 10 months,” Blackwell said. “I hope advocates get out to the House. Give the Speaker a call.”

Democratic Sen. David Blount, a co-author of the bill, wrote on Twitter on March 9, that the decision to kill the bill was “a failure that will deny mothers the health care they need.”

The Senate passed a resolution on Tuesday to suspend the rules and revive a bill that could extend postpartum Medicaid in the state. It’s up to the House to pass it in the next few days before the session ends on Monday.

Jane Adams, director of the Cover Alabama coalition said Medicaid “isn’t a bad word here,” in Alabama when comparing her state’s expansion efforts to Mississippi’s.

The Cover Alabama coalition has been meeting with lawmakers, who have been open to hearing their concerns. Trying to extend care is just an extension of benefits women already had, and it can be easily passed through a new option offered by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

“I think the Mississippi circumstances are very different from Alabama’s,” Adams said. “There’s been a consistency of support for reducing maternal mortality in our state. Mississippi’s Speaker is the opponent. Ours is not.”

CDC data show at least a quarter of pregnancy-related deaths happen up to a year after delivery, and the Gulf South has some of the highest maternal mortality rates in the nation. While the national rate is 20.4 maternal deaths per 100,000 births, the rate is 30.2 in Mississippi, 31.8 in Louisiana, and 36.2 in Alabama.

There’s already momentum for a full-year extension in other southern states, like Georgia. Others, like Tennessee, already did it in 2021. This gives Adams hope that lawmakers will follow suit and support postpartum Medicaid and get it funded through the state’s budget.

Many Mississippi Republican lawmakers and advocates also say opposing postpartum Medicaid contradicts the state’s pro-life agenda. The state is currently asking the Supreme Court to allow it to ban all abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

Mississippi Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann‘s office is close to Gunn’s office, sitting on the same floor just across the capital divide from each other. The two Republicans, however, could not be further apart from each other on the issue. While Hosemann wants attention on postpartum Medicaid — among other things like infrastructure — Gunn has pushed the issue to the backseat, focusing instead on a massive tax reform he has been pushing for over a year.

“We have the most postpartum births with problems, and we have the most deaths, higher than the national average,” Hosemann said. “We’re trying to be consistent in arguing for the right to life on one side and taking care of the baby once they get here.”

Playing politics with women’s lives

Black women are up to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related issues in Alabama and Mississippi. When Gunn shut down the legislation without a discussion, Mississippi resident Whitney Batteast was shocked. She was hoping the legislature would seek to rectify this disparity.

“We know so many things can happen in that first year, so why should it not be covered?” Batteast said. “A lot of deaths are preventable if those women had the reassurance that they would be covered […] and knew that they could go to the doctor.”

Batteast knows from personal experience the significance of health coverage. Two years ago, she was denied private health insurance when she was pregnant, forcing her to enroll in Medicaid.

She knew from her other children that the cost of giving birth could be tens of thousands of dollars, and she also knew her pregnancy wouldn’t be easy. With her first two kids, she suffered from intense week-long migraines. But this time was worse — her blood pressure kept spiking.

“I got induced at 39 weeks and we had the baby. I stopped taking medication because no one told me to continue. So, I’m thinking everything is going to be fine,” Batteast said.

But, Batteast was later diagnosed with preeclampsia, a pregnancy complication highlighted by dangerously high blood pressure, which is one of the leading causes of postpartum maternal death. Even though her life was at risk, she struggled to get care.

“I also realized that same day was the day my Medicaid ran out,” Batteast said. “That’s when everything prior to that clicked about how I would have been treated. The services that I did not receive were solely based on my thought of my inability to pay.”

Medicaid is a significant safety net for women who fall in the coverage gap during their pregnancies. For some women, Medicaid isn’t just critical to physical health, but also mental health — treatment for which can extend well beyond 60 days after birth.

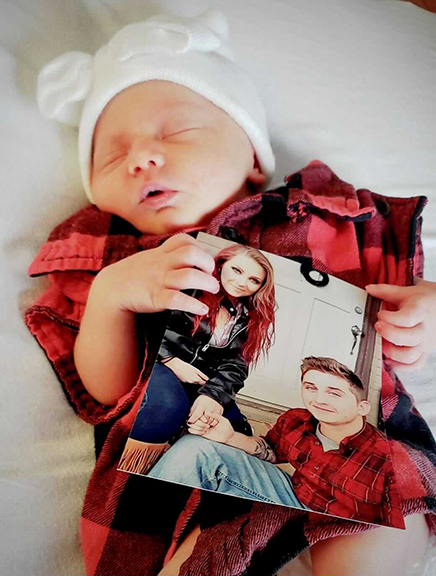

Alabama resident Brittany Kendrick, who is white, gave birth to her daughter Khaleesi about 8 months ago. She had to have her early, like Batteast, because of high blood pressure. Making matters worse, Kendricks, just 28 years old, is a single mother because her fiance died in a car crash last year.

“He was in a head-on collision and passed away before getting to hear the heartbeat,” Kendrick said. “I was only four months pregnant.”

Kendrick got on Medicaid to cover her daughter’s birth. Being able to stay on Medicaid during the public health emergency has been a relief, like when both Kendrick and Khaleesi got sick with COVID-19 just three weeks after Khaleesi was born. She’s also suffering from severe postpartum depression and grief from the death of her partner.

Kendrick said it’s wrong for people to think that women who get on Medicaid are just trying to take advantage of the public health system.

“My Medicaid is still active. And that’s the only way I’m getting my anxiety and depression medicine now,” Kendrick said. “I don’t know what I’m going to do if they cut that off.

“For people in my case who truly need it, it’s such a blessing. How do they expect anybody to get ahead in life, move forward and be better? Everybody needs a little bit of help every once in a while.”

A legacy of racism that continues to harm all women’s health

Adams says Alabama lawmakers see extending Medicaid for women as a good business deal for the state and a human rights issue. The state’s report found that 70% of pregnancy-related deaths in 2016 were preventable.

“We absolutely say it is a moral issue for our coalition,” Adams said. “Our key principle is that we believe in health care for every single person in Alabama.”

Policy aside, the state’s “horrific legacy” of medical racism is also a present hurdle to clear. James Marion Sims, an Alabama doctor known as the father of modern gynecology, experimented on enslaved womens’ bodies and developed techniques that are still used today.

Cassandra Welchlin, head of the non-profit Mississippi Black Women’s Roundtable, says services that could support Black women often don’t get the funding they deserve — even though they also serve the greater population as well — because of lingering racism in Mississippi and the Gulf South.

“I think the difference between all of these states is really leadership and who is willing to do what’s right,” Welchlin said. “You can’t be a lawmaker in these southern states without having a racial and gender lens to how we do this work.”

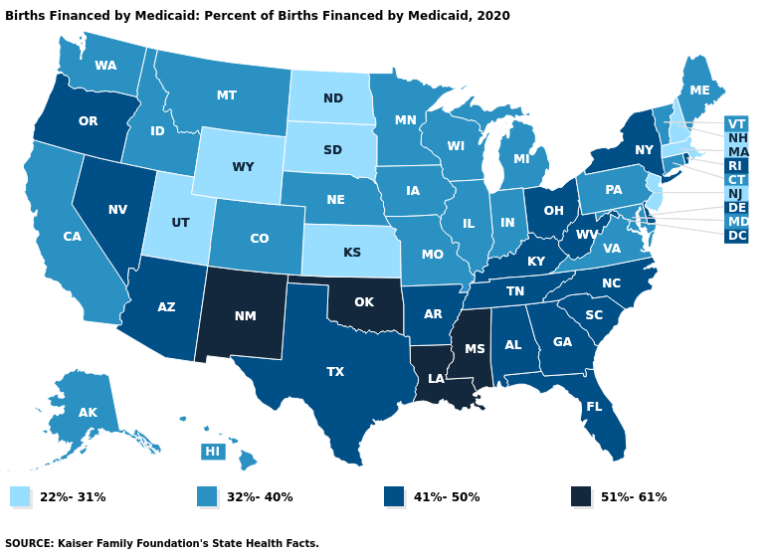

Nearly one in five people in the U.S. — or around 59 million people — use at least one type of social safety net programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and Medicaid in the average month, according to a 2019 Urban Institute study. Although non-Hispanic Black people are more likely to participate in one of those programs, the largest share of total participants is white.

Louisiana has the most births on Medicaid in the nation. The state, however, is the outlier in the Gulf South, choosing to expand Medicaid in 2016 under Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards — allowing more women in general to access care. The state also has plans to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage to a full year for women who might not be covered under that expansion.

Meanwhile, women in Mississippi and Alabama are among the top five states for Medicaid use among pregnant women. Half of all births in Alabama are financed by Medicaid. In Mississippi, that number jumps to 60% of all births. Between 2008 and 2012 in Mississippi, 87% of Black women giving birth and 53% of white women giving birth were insured by Medicaid.

One significant difference, Welchlin says, is the postpartum outcomes.

“Of course, If there were more white women and white babies dying, there would be more of an effort. But we don’t see that,” Welchlin said.

Her office sits directly down the road from the State Capitol. She remembers watching her mother struggle to make ends meet as she only earned a couple of dollars an hour in janitorial work there. Her mother couldn’t afford childcare, so Welchlin used to wait for her to get off work in a utility closet.

Like most other advocates who thought the Medicaid legislation was destined for the governor’s desk, Welchlin was also dismayed by its downfall.

“I’ve lived the struggle and I know what those safety nets do to save lives,” Welchlin said.

For now, advocates will continue to fight for postpartum Medicaid to save women’s lives. The next step to make it happen, Welchlin said, is for white women to stand with them.

“What we need are white women to stand up with us, even more, to say this is important,” Welchlin said. “Philip Gunn needs to be concerned, not just with white lives, but also with Black lives, Latina lives, Asian indigenous women lives. It’s about all of us because we make up all Mississippians.”

In the meantime, mothers like Batteast aren’t waiting around to see more mothers die.

She started a non-profit to support women during and after their births called Pickles and Popsicles — named after her favorite pregnancy cravings. Batteast said she knows that support from leadership may not come, so it’s important for women to be advocates among themselves.

“I had to kind of create my own little village of support,” Batteast said. “I want it to be that village for someone else.”

This story is part of The Holdouts, a reporting collaborative focused on the 12 states that have yet to expand Medicaid, which the Affordable Care Act authorized in 2010. The collaborative is a project of Public Health Watch.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration among Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama and WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR. Support for health equity coverage comes from the Commonwealth Fund.

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.

Trump’s ballroom project can continue for now, court says

A US District Judge denied a preservation group's effort to put a pause on construction

NASA lost a lunar spacecraft one day after launch. A new report details what went wrong

Why did a $72 million mission to study water on the moon fail so soon after launch? A new NASA report has the answer.

Columbia student detained by ICE is abruptly released after Mamdani meets with Trump

Hours after the student was taken into custody in her campus apartment, she was released, after New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani expressed concerns about the arrest to President Trump.

These major issues have brought together Democrats and Republicans in states

Across the country, Republicans and Democrats have found bipartisan agreement on regulating artificial intelligence and data centers. But it's not just big tech aligning the two parties.