Alabama’s ‘ultimate school choice’ bill gets complicated when considering race and poverty

The Parents’ Choice Act is outgoing Republican Sen. Del Marsh’s Hail Mary for education reform. SB140 has been dubbed the “ultimate school choice” bill because it would give participating parents $5,600 per kid in state money deposited in an education savings account to use for private school or another public school. Marsh said this bill will put everyone on a level playing field.

“All I’m trying to do is do all I can to get parents involved in their children’s education and give them options that they’ve never had before,” Marsh said. “And I think doing so is in no way detrimental to the public school system.”

Marsh cited Alabama’s low standardized test scores as a reason why he believes it’s time for a sweeping change in education. He said schools should be held accountable.

“I just think in doing that, it creates competition in the public sector, which I think is a good thing,” Marsh said. “I believe in the free market, and I think a lot of Alabamians do, and it’s time to force the public system to make some changes and address these issues of low test scores and declining act scores.”

Other proponents of this school choice bill think it will create new opportunities for students. But critics said it’s not so simple. School choice is complicated by economic and racial disparities.

“We’re not selling products like a T-shirt that you can get at Walmart,” said Jonathan Hale, an education policy professor at the University of Illinois. “We’re dealing with young people’s lives and the livelihood of families.”

Last year, Hale published a book about school choice and race titled The Choice We Face: How Segregation, Race, and Power Have Shaped America’s Most Controversial Education Reform Movement.

He said there are deep structural issues in Alabama’s education system that won’t be solved by offering cash to parents.

“School choice does not help the majority of students and families who really are demanding a better education,” Hale said.

Hale said you can’t talk about parents having the power to choose where their kids go to school without talking about how that power perpetuates racial inequalities in education.

“You’re talking about choice and that takes us away from any discussion about race and racial equity,” Hale said. “This is the United States. If that question is not at the forefront, policy is going to actually be working against that.”

When pressed on whether this bill would benefit parents of all races, Sen. Marsh said this bill isn’t about race nor does the legislation mention race. But education in the South still sees the effects of segregated schools from generations ago, and it’s resulted in unequal education outcomes.

Research from the Center for Education and Civil Rights, a research collective, found that school choice tends to increase inequality and segregation. That’s because, if given the choice, parents of all backgrounds tend to send their kids to schools with people similar to themselves.

Hale said for this bill to really benefit everyone, it would have to put more power in the hands of local groups.

“I think the writing is on the wall in the state of Alabama and other deep Southern states, that Black communities will only benefit or the majority within a Black community will benefit if it is controlled by those local families and local decision makers,” he said.

For some Black and brown parents, having the ability to choose their kids’ schools is empowering, but it only goes so far. For example, the bill is opt-in for both parents and schools. So, schools don’t necessarily have to accept students trying to transfer.

According to Peter Jones, who teaches education policy and finance at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, the parents likely to opt-in to the education savings accounts are probably already affluent and have an increased interest in their children’s education.

“One of the things that we know about education outcomes in this state, in particular, is they’re driven a lot by poverty,” Jones said. “This bill is unlikely to really address some of those underlying issues associated with poverty.”

For example, the bill doesn’t address issues like transportation. Not all parents’ schedules allow them to take their kids to a different school themselves and buses aren’t always available. This bill could also take money away from under-resourced traditional public schools. The Legislative Fiscal Office estimated the program would cost $537 million if fully implemented. Jones said it’s a big chunk from the Education Trust Fund.

It’ll also put schools in the position to feel like they have to compete for funding.

“So what the school choice bill would mean would really kind of throw the system into kind of a havoc of trying to understand what parents are wanting and where they’re moving,” Jones said. “What that’s going to mean for Birmingham City Schools is that they’re essentially going to lose some of the more motivated parents.”

Supporters of the Parents’ Choice Act believe that kind of competition is a good thing because schools should be more responsive to parents.

“I think it creates a greater accountability from teachers and a greater accountability from school districts when they know that parents do have some say in the per pupil funds,” said LaShunta Boler, a mother to four school-aged kids in Birmingham.

The Bolers have three kids in the Birmingham City Schools and one in a charter school. She and her husband said they’re loyal to BCS and that they’re happy with their kids’ education, but they think this school choice bill could help others.

“We have friends and relatives and church members and mosque members, and we have different people who have different stories. And so I’m willing to try it for the benefit of them,” Boler said.

She said she does hope, however, that if this bill passes, it’ll have safeguards in place to protect parents from being exploited for their money. She also wants there to be community sessions to educate parents about how the education savings accounts work.

No state leader defends Alabama’s low education rankings, but it’s up to lawmakers to decide if this bill, with its entanglement with race and poverty, is a solution to the state’s academic achievement problems.

Kyra Miles is a Report for America corps member reporting on education for WBHM.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

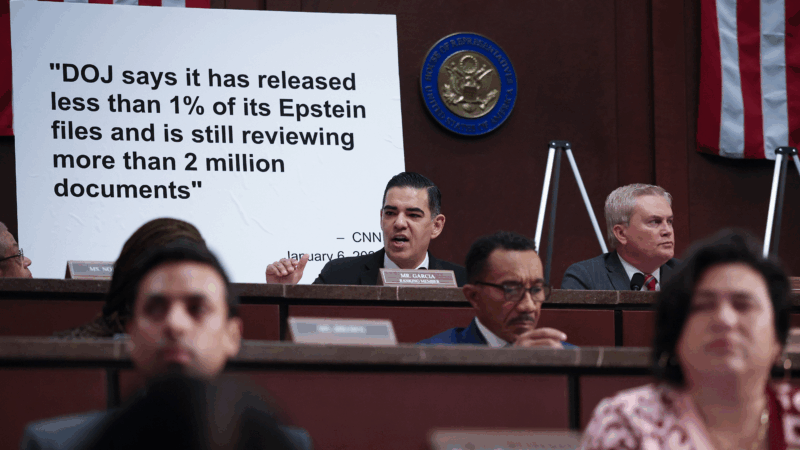

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

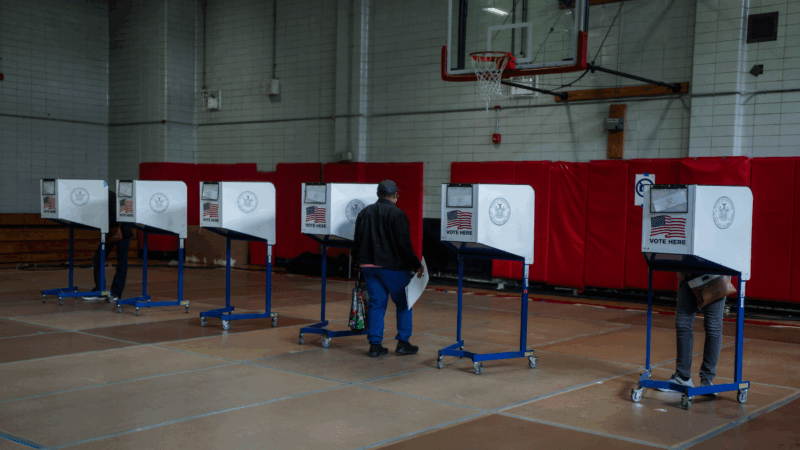

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.

Surgeon general nominee Means questioned about vaccines, birth control and financial conflicts

During a confirmation hearing, senators asked Dr. Casey Means about her current positions and her past statements on a range of public health issues.

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame 2026 shortlist includes Lauryn Hill, Shakira and Wu-Tang Clan

The shortlist also includes a 1990s pop diva, heavy metal pioneers and a legendary R&B singer and producer.