6 ways the conversation around a guaranteed income in the US has changed

Guaranteed Income Now attendees speak between conference sessions in Atlanta, Sept. 29, 2022. From left to right: Kim Drew, Jody Chong and Dominique Derbigny Sims.

It’s a good time to be a guaranteed income fan.

The idea that giving struggling people regular cash payments — without any strings attached — is the best way to help is getting tested across the country. There are more than 50 guaranteed income pilots happening now in 24 states, and Washington D.C.

Plus, recent data on the Child Tax Credit — a policy from the American Rescue Plan that some see as a type of guaranteed income — suggests it significantly reduced child poverty, which advocates hold up as proof that a federal guaranteed income policy can work.

Recently, many of those advocates gathered in Atlanta for a conference to discuss the movement’s gains and how to push for a permanent guaranteed income. The conference is a sequel to a 2017 conference held in San Francisco, back when guaranteed income was just wishful thinking. While the idea has been around since long before Martin Luther King Jr. championed it, the movement has come a long way.

Here are six ways the guaranteed income movement has changed since then.

Pilots in motion

During that 2017 conference, hosted by the Economic Security Project, guaranteed income wasn’t much more than a Silicon Valley cocktail party topic — an intriguing idea with no one in this country really testing it.

At the time, Stockton, California Mayor Michael Tubbs announced he’d be running a guaranteed income pilot in his city, but even that was two years away from launching.

Today, practice has caught up to theory with pilots spread across the country. Instead of wondering what happens when you send people monthly deposits, Atlanta’s conference attendees could just ask.

Tomas Vargas Jr. is used to sharing his guaranteed income story.

Vargas was one of the 125 Stockton residents who received a guaranteed income as part of Tubb’s two-year-long program from 2019-2021. Along with the money helping him clear his debt, Vargas said it made him feel more confident. A study on the Stockton pilot backed up Vargas’ experience, showing improved well-being and financial stability for the recipients.

“It gave me opportunities to look at myself in a different light instead of the darkness I was always used to,” Vargas said during the conference.

He now works as an administrative associate for Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, which funds many of these programs.

While guaranteed income is pretty simple by welfare policy standards — send money to those in need — the pilots are all trying different approaches. In Jackson, Mississippi, a long-standing pilot gives moms living in affordable housing $1,000 a month, while a new one in New Orleans has been sending $350 a month to young adults. San Francisco is helping artists hurt by the pandemic and Birmingham, Alabama’s program has no income cap.

All these different pilots are being used by MGI and others to build a case for a national program. The pilots are all being studied by researchers and spending data from 20 city pilots was recently released.

A shift from tech to civil rights

That 2017 guaranteed income conference — then called Cash-Con — was based in San Francisco, and the tech-heavy location reflected the movement’s priorities at the time.

Guaranteed income promoters pitched the cash payments as a way to stifle the job-loss pain the tech sector would inevitably bring with automation. Universal income was also a more popular idea then — which would give money to everyone instead of targeting people in need.

But, addressing the impact of automation with guaranteed income feels like solving a problem of the future, said Economic Security Project Co-Chair Natalie Foster. Her organization co-founded MGI, which funds many of the city pilots.

“No policy passes because of something people are worried about in the future,” Foster said.

This year’s conference in Atlanta put it in the heart of the region’s deep civil rights history, reflecting the shift away from tech concerns and toward economic justice. Equity and shrinking the racial wealth gap have become the center of the guaranteed income discussion.

Martin Luther King Jr’s youngest daughter, Bernice King, was the keynote speaker of this year’s conference. Her father pushed for a guaranteed income before he was assassinated, and said he believed it could address economic injustice, which he called an inseparable twin of racism.

She thanked the mayors in the crowd for advancing her father’s work. But she said pilots can’t be the endpoint.

“I appreciate that you all started this,” King said. “But we got to get it codified in federal law. When daddy spoke about it, he was talking about — not something temporary. He was talking about something permanent.”

The Child Tax Credit: A pandemic test case

Throughout the pandemic, Congress kept relying on the same tool for dealing with the economic fallout of the pandemic — cash. Americans received stimulus checks, unemployment checks got boosted and there was the child tax credit.

While the tax credit has been around since 1997, Congress made a few key changes to it with the American Rescue Plan. Before, some families missed out on the credit since they didn’t owe income taxes. The new version offered cash for those families instead — between $250 and $300 per child each month.

Those changes meant it essentially functioned as a guaranteed income for families with low incomes.

Proponents held up the policy as an example that a federal guaranteed income can work. While the expanded program only sent out the checks for six months before reverting back, child poverty fell nearly in half last year, in large part due to the child tax credit, according to officials with the U.S. Census Bureau.

“We defied gravity and reduced poverty in the midst of a pandemic,” Foster said.

Make it permanent

More than 30 additional pilots are planned going forward. But, while the pilots have helped individuals who receive checks, they’re ultimately just tests.

The big ambition for advocates? Turning these test runs into permanent policy.

“Policy is frozen power,” Foster said. “It’s something that people can count on, for perhaps a lifetime.”

The second day of the Atlanta conference was mostly dedicated to making the jump from pilot to policy. Closed-door sessions focused on strategy and using data and stories from the pilots to sell the idea of guaranteed income to state legislatures.

But a federal guaranteed income policy is the ultimate goal. Michael Tubbs has gone from Stockton mayor to cofounder of MGI. At the conference, he said the federal government can better fund guaranteed income because it has greater freedom to take on debt.

“As mayors and county officials we have to balance our budgets, which is why we have to do pilots,” Tubbs said. “The federal government is able to invest.”

Inflation fears

While Congress can spend with more freedom than states and cities, that doesn’t mean it can do it without consequences.

As the country faces record-high inflation, some economists are placing the blame for it on government spending on pandemic aid — and the expanded child tax credit is one of the policies accused of driving price hikes.

Organizers of the guaranteed income movement are recognizing that they’ll have to face down critics who will use high inflation to push back against the idea.

Supporters point to a letter signed by 133 economists arguing that the child tax credit was too small to have a meaningful effect on inflation and that one way to help families hurt by the higher prices is by bringing the expanded credit back.

Sukhi Samra, director of MGI, said lots of factors contribute to inflation — such as the country’s gnarled supply chain — and it’s unfair to point the finger at the child tax credit alone.

“It’s really easy to place blame on the thing that is helping the Americans that don’t typically get help,” Samra said. “When we see the stimulus checks and we see the child tax credit, we see it overwhelmingly affecting Black and Brown families. So it’s no surprise that the discourse around it is to attack that very tool.”

Taxes as the path of least resistance

While supporters hold a federal guaranteed income as their top ambition, that might not be realistic if Democrats fail to hold onto Congress.

So the movement is working on another strategy — bringing the expanded child tax credit model to the states.

Vermont’s already doing so. In May, Gov. Phil Scott signed a law that will send $1,000 per child under six to families earning less than $125,000 each year. Advocates now want to make the checks monthly. New Jersey and New Mexico passed similar legislation.

Economic Security Project announced at the Atlanta conference it was investing $1 million to push for more states to take this tax route. The organization views this as both a way to build more research in favor of a guaranteed income and as one of the fastest ways to get money into more people’s pockets. The mindset is that it’s politically easier to alter existing policies like tax credits than it is to create a guaranteed income from scratch.

“One of the big shifts was saying you could use the existing tax credits and expand them,” Foster said. “That was one of the ‘ah-has.’”

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story incorrectly cited the organization that was investing $1 million to help more states pass their own version of a child tax credit.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration among Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama and WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

The candy heir vs. chocolate skimpflation

The grandson of the Reese's Peanut Butter Cups creator has launched a campaign against The Hershey Company, which owns the Reese's brand. He wants them to stop skimping on ingredients.

Scientists make a pocket-sized AI brain with help from monkey neurons

A new study suggests AI systems could be a lot more efficient. Researchers were able to shrink an AI vision model to 1/1000th of its original size.

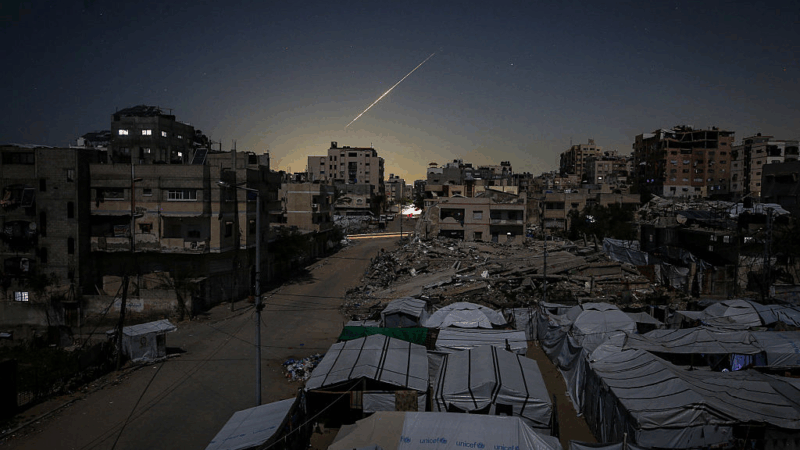

U.S. evacuates diplomats, shuts down some embassies as war enters fourth day

The United States evacuated diplomats across the Middle East and shut down some embassies as war with Iran intensified Tuesday while President Trump signaled the conflict could turn into extended war.

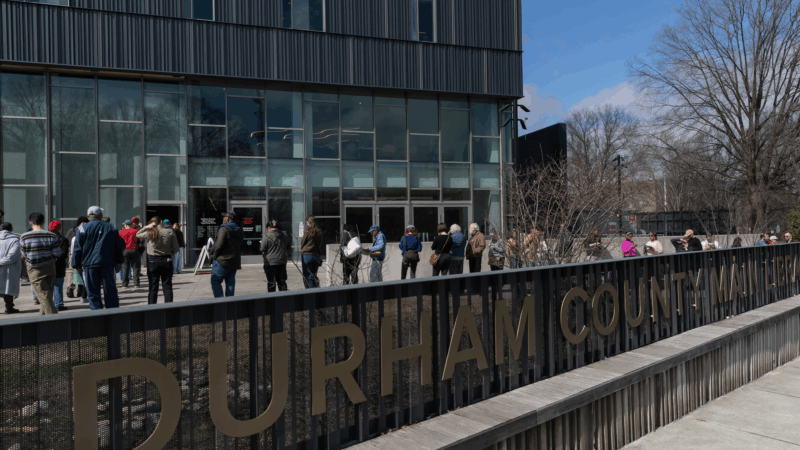

North Carolina and Texas have primary elections Tuesday. Here’s what you need to know

The midterm elections are officially underway and contests in Texas and North Carolina will be the first major opportunity for parties to hear from voters about what's important to them in 2026.

Kristi Noem set to face senators over DHS shutdown, immigration enforcement

The focus of the hearing is likely to be on how Kristi Noem is pursuing President Trump's mass deportation efforts in his second term, after two U.S. citizens were killed by immigration officers.

College students, professors are making their own AI rules. They don’t always agree

More than three years after ChatGPT debuted, AI has become a part of everyday life — and professors and students are still figuring out how or if they should use it.