Environmental Groups Say Water Board Isn’t Effectively Protecting Drinking Water Supply

Two local environmentalist groups are suing the Birmingham Water Works Board, alleging it failed to comply with a 2001 consent decree that ordered the protection of undeveloped land around the Cahaba River watershed, a major source of Birmingham’s drinking water.

Cahaba Riverkeeper and the Cahaba River Society, represented by the Southern Environmental Law Center, have filed a complaint in Jefferson County Circuit Court hoping to compel the BWWB to place permanent protections, overseen by an independent third party, on its landholdings surrounding the Cahaba River, the Little Cahaba River and Lake Purdy.

The lawsuit cites the worry that, because the land in question is “some of the last undeveloped land in a rapidly urbanizing area,” the BWWB may cave to “intense development pressure.”

In some cases, plaintiffs say, the board already has.

The lawsuit argues that the board has long ignored a 2001 settlement agreement with Alabama then-Attorney General Bill Pryor that required the board to place permanent conservation easements on the thousands of acres of watershed property it owns, preventing all future development.

But while the BWWB publicly maintained that it was in compliance with that order and “committed to the conservation easements,” it didn’t officially instate protections until October 2017. Plaintiffs argue that the board is still in violation of the 2001 agreement and that what it implemented in 2017 were easements in name only and “not legally valid.”

Cahaba River Society Executive Director Beth Stewart called the BWWB’s easements “a stopgap [that] doesn’t give the legal standing or strength that a conservation easement is supposed to have.”

The lawsuit argues that the 2017 easements are not valid because they are held by the BWWB and not a third-party trustee. According to Alabama state law, a property owner “cannot have an easement to his or her own property” because their rights of ownership extinguish any other obligations. As such, the BWWB can change the terms of its “easement” at any time for any reason, so long as the state attorney general signs off on it.

BWWB committee meeting minutes indicate that the board seriously considered selling some of its “excess properties” in the area as recently as 2019. The lawsuit notes that the board sold one parcel of supposedly protected land on Grants Mill Road to developers of a gas station in 2016, while another protected parcel was cleared by the BWWB to make way for roads and fencing in January 2020.

Plaintiffs say development could cause a drop in both cleanliness and quantity in one of the area’s largest sources of drinking water. The forested lands in question serve as a natural riparian buffer, filtering out sediment and contaminants from stormwater runoff that otherwise would go directly into Lake Purdy, a drinking water reservoir, or the Cahaba River, where the BWWB’s drinking water intake is located. The Little Cahaba connects those two bodies of water.

“That forest is like a giant sponge,” Stewart said. “When it rains, the forest is holding the water and getting it into the groundwater and keeping it clean. … Every time that you remove forest and replace it with paving and roofs, that’s a part of the sponge that’s gone.”

Paving over this natural “sponge” would prevent the watershed’s groundwater supply from replenishing. That groundwater replenishes the Cahaba River, too — which means that development of the woodlands would likely cause the river’s overall water level to drop during drier seasons.

Then Birmingham residents could also see their bills increase as filtration costs go up, according to Stewart.

“These are public lands that ratepayers have already paid for to protect their drinking water and keep treatment costs affordable for themselves and future generations,” Stewart said. “If Cahaba water is degraded, every Water Board customer has to pay more.”

David Butler, staff attorney and riverkeeper for Cahaba Riverkeeper, said the lawsuit is a last resort, filed after years of lobbying the BWWB.

“We’ve presented to the Water Works Board numerous times and have tried to find a mutually agreeable solution, and there really just was no movement,” Butler said. “Considering that these easements should have been filed 21 years ago, we feel like we’ve waited long enough.

“Our position is, the 16 years that lapsed between the settlement agreement and the filing of what are purported to be conservation easements is evidence that we need stronger protections,” Butler said. “Those easements were supposed to be filed within 30 days of the 2001 agreement. Certainly, 16 years is longer than 30 days, and the effort to sell the land in the meantime goes against what the original settlement agreement intended.”

The Birmingham Water Works Board responded to the lawsuit Monday afternoon with a statement from spokesperson Rick Jackson:

“Birmingham Water Works is committed to providing the highest quality water to our entire service area. We have a long track record of fighting to protect all our various sources of water supply, including all the lands surrounding Lake Purdy and the Cahaba River. Our attorneys are in the process of reviewing this lawsuit and will take the appropriate action to properly respond to it in court.”

Oil prices rise sharply in market trading after attacks in Middle East disrupt supply

The high prices came as U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran and retaliatory strikes against Israel and U.S. military installations around the Gulf sent disruptions through the global energy supply chain.

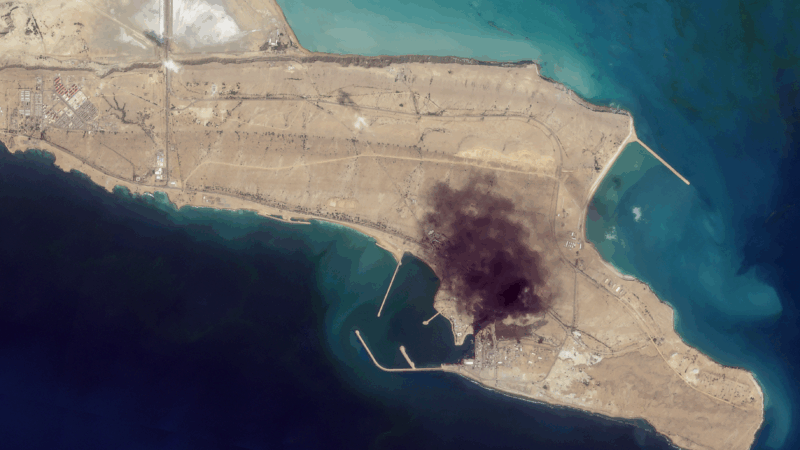

Satellite images provide view inside Iran at war

Satellite images from commercial companies show the extent of U.S. and Israeli strikes, and how Iran is responding.

Mideast clashes breach Olympic truce as athletes gather for Winter Paralympic Games

Fighting intensified in the Middle East during the Olympic truce, in effect through March 15. Flights are being disrupted as athletes and families converge on Italy for the Winter Paralympics.

A U.S. scholarship thrills a teacher in India. Then came the soul-crushing questions

She was thrilled to become the first teacher from a government-sponsored school in India to get a Fulbright exchange award to learn from U.S. schools. People asked two questions that clouded her joy.

Sunday Puzzle: Sandwiched

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with WXXI listener Jonathan Black and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

U.S.-Israeli strikes in Iran continue into 2nd day, as the region faces turmoil

Israel said on Sunday it had launched more attacks on Iran, while the Iranian government continued strikes on Israel and on U.S. targets in Gulf states, Iraq and Jordan.