Economic Opportunity, Community Policing Among Solutions To Birmingham’s Gun Violence

The family of Rondarius Bryant were in attendance at Kelly Ingram Park led by the Mothers Who Want The Violence To Stop.

Birmingham has been riddled with crime for decades, and people are concerned about the increasing number of homicides. In 2020, violent crimes such as rape and robberies decreased, but gun-related violent crimes increased almost 20%. Last year ended with a total of 122 homicides, the most in the last 25 years. So far in 2021, there have been at least 60 homicides in the city of Birmingham, according to data from the Jefferson County Coroner’s Office.

Local officials are trying new things. This summer, the Birmingham police are opening a real-time crime center, a tech hub providing live updates. They are also working with Crime Stoppers to get tips that will lead to arrests and hopefully end the no-snitch culture. And, there’s a new federal partnership to improve safety at the city’s 14 public housing properties.

However, some people are wondering if that’s enough.

“I think that the schools need to make some kind of provision for them to have some kind of good job,” said Apostle Wanda Stephens. “You see what I’m saying? Not to go out and get a job that’s paying seven, eight dollars.”

After Stephen’s son was killed in 2006, she turned her grief into action by starting the organization Mothers Who Want The Violence To Stop. Stephens wants city and school leaders to enact more systemic solutions.

Research shows that one issue that leads to crime is income disparities. Almost 30% of Birmingham residents live in poverty. Lonnie Hannon, who is a behavior health professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said that people like to live in what’s considered societal norms.

“Like, to be able to purchase a house, to wear specific types of clothing, to drive certain types of cars, to provide certain resources to the family,” Hannon said. “Then you have to find ways to increase legitimate opportunities for the people who are experiencing what I call, you know, chronic poverty.”

Hannon said if people aren’t feeling that they fit within those social norms of income, then they’re willing to take risks to get there. This is common among urban communities.

Birmingham could learn some lessons from Camden, New Jersey, which has served as a model city for decreasing its crime rates. In 2013, the city of Camden disbanded its police force and rebuilt it with a focus on community policing. That year, the city had a total of 57 homicides, but in 2020, they only had 17. That’s a 67% decrease. Camden County Commissioner Louis Cappelli attributed the city’s success to focusing on building community relationships.

“Trust has led to a tremendous partnership between residents and police that helps us to solve crimes, prevent crimes,” Capelli said. “[It lets] us know where there might be some hotspots or bad things happening.”

Jeffrey Walker, who leads the department of criminal justice at UAB, endorses community policing. For example, he said police can walk and interact with people in their neighborhoods at particular times.

“If you look at Camden, that’s a lot of what they did. They just started doing some very serious interaction with the community,” Walker said.

While the idea of defunding the police has grown more popular nationally, Hannon said he doesn’t agree with that. He pointed to other longer-term solutions.

“Do I feel as if we should invest in mental health, should we invest in education, should we invest in de-escalation tactics? Yes, I do,” Hannon said.

One program that’s taking that community-minded approach is the Birmingham Promise. It guarantees qualifying Birmingham City School students free college education. This gives at-risk kids a chance to elevate their economic status without the burdens of student loan debt. This is a longer-term solution that may take years to see the full results, but all of these efforts could make a difference in Birmingham.

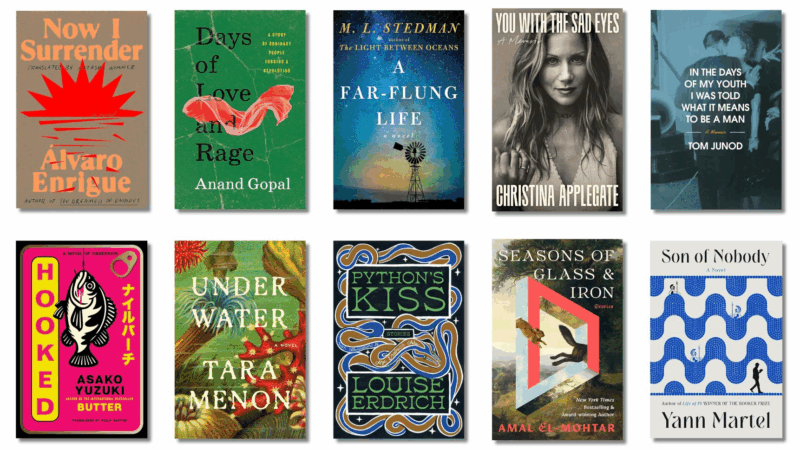

10 new books in March offer mental vacations

March is always a big one for books – this year is no different. We call out a handful of upcoming titles for readers to put on their radars — offering a good alternative to doomscrolling.

Sen. Chris Coons, D-Del., talks about the war with Iran and upcoming war powers vote

NPR's A Martínez asks Delaware Democrat Chris Coons, a member of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, about the war with Iran.

The candy heir vs. chocolate skimpflation

The grandson of the Reese's Peanut Butter Cups creator has launched a campaign against The Hershey Company, which owns the Reese's brand. He wants them to stop skimping on ingredients.

Scientists make a pocket-sized AI brain with help from monkey neurons

A new study suggests AI systems could be a lot more efficient. Researchers were able to shrink an AI vision model to 1/1000th of its original size.

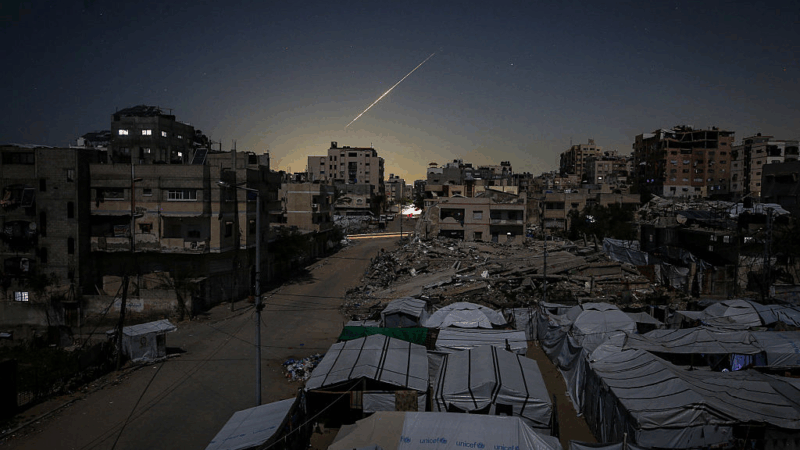

U.S. evacuates diplomats, shuts down some embassies as war enters fourth day

The United States evacuated diplomats across the Middle East and shut down some embassies as war with Iran intensified Tuesday while President Trump signaled the conflict could turn into extended war.

Kristi Noem set to face senators over DHS shutdown, immigration enforcement

The focus of the hearing is likely to be on how Kristi Noem is pursuing President Trump's mass deportation efforts in his second term, after two U.S. citizens were killed by immigration officers.