Nonprofits Adapt To Harsh Financial Conditions After Birmingham Budget Cuts

The FY 2021 budget passed Tuesday night by the Birmingham City Council contains a number of austerity measures stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, which since March has stymied the local economy and caused the city’s business tax revenue to plunge.

The budget, which was approved by the council with no changes to Mayor Randall Woodfin’s original proposal, is nearly $50 million smaller than last year’s and cuts the city’s contributions to schools, libraries and public transit, among other departments.

Some of those changes have proven controversial, but other cuts — particularly those to external nonprofit organizations such as the Birmingham Zoo, Jones Valley Teaching Farm and Ruffner Mountain Nature Preserve — went largely unquestioned even by opponents of Woodfin’s budget.

Leaders of those nonprofits say they were unsurprised by the cuts, and even before the budget’s passage, they appeared resigned to the loss. Instead, faced with their own significant budget shortfalls, those organizations are adapting to survive a hostile, post-COVID landscape.

“We’re Going to Do Our Best”

For some organizations, the economic slowdown caused by the pandemic has made the loss easier to take. Film Birmingham, the Create Birmingham initiative dedicated to attracting film productions to the Magic City, had its entire $50,000 allocation, which accounts for roughly half its overall budget, axed from the budget.

Because COVID-19 has shut down most film production nationwide, anyway, the initiative can afford to go dormant, with staffers refocused to other parts of Create Birmingham. “In the immediate, there is not a lot of work occurring (with the Film Initiative),” said Create Birmingham President and CEO Buddy Palmer. “That’s not to say we don’t have fixed expenses; we do, but for the moment we are covering those.”

Instead of trying to recoup the film initiative’s lost funds, that energy’s been shifted toward small business programming.

“When we are fundraising in our philanthropic community at the moment, it is really to support the work we do around entrepreneurship and small business, and that’s a whole other conversation, because all of the business that falls within tourism — leisure, entertainment, hospitality — is the hardest hit piece of the economy, and so much of that is made up of small business.”

Some Birmingham nonprofits have been negatively affected by the tourism slowdown, too, for instance, the Birmingham Zoo, an organization also having to contend with a funding cut from the city.

Although the city owns the facility, zoo operations are managed by a separate nonprofit that relies on the city for 18% of its budget — at least, it did before COVID-19. Now, the city’s funding is expected to decrease by 75%, from $2.08 million to $500,000.

It’s another tough loss in a year of tough losses for the zoo, which also has had to contend with diminished attendance numbers. Ticket sales, which typically make up about 30% of the zoo’s budget, have dropped to about one-third of what they were last year.

“This is a large cut to us that, as a sudden cut, is obviously more difficult to plan for how to overcome the impact,” said Chris Pfefferkorn, the zoo’s president and CEO. “But that’s what we’re going to do. We’re going to do our best.”

The zoo has taken steps to lessen operating costs, including closing on Mondays and Tuesdays, which allowed them to compress most of their staff into a five-day workweek. They’ve had to lay off five employees in their education, finance and volunteer departments, and senior team members have taken salary cuts. Education programs also have been cut, with remaining offerings being retooled to accommodate social distancing.

This year’s cuts mean that more pressure than ever is on its annual fundraising gala, which has moved online this year, and holiday events such Boo at the Zoo and Zoo Lights, which will have to be “rethought,” Pfefferkorn said, due to both COVID-19 and a reduced event budget.

It takes $35,000 a day to keep the zoo open, including $1,000 a day just to feed the animals. It’s likely the zoo will receive some corporate assistance. A few companies already have reached out “to see how they can help,” Pfeffekorn said. But more than ever, the zoo will rely on public donations to survive.

“We are just going to have to refocus whatever revenue we have into maintaining the facility we have and keeping it going,” Pfefferkorn said. “I’m very optimistic that we’re going to continue to operate because our community has supported us so well over the 65 years that we’ve been in existence. … I think a lot of the citizens recognize that and I think it’s why they do support us so well.”

“It’s Not Easy for Anyone at This Point”

Amanda Storey was not surprised when Jones Valley Teaching Farm’s $50,000 allocation was axed by the new budget. “I don’t know how we could have received it based on the income that was lost from their budget,” said Storey, the farm’s executive director. “We’re just holding tight and seeing what happens the rest of the year and early next year.”

The city’s allocation wasn’t a huge part of JVTF’s $1.8 million budget, though, as Storey noted, for a relatively small nonprofit, “every little bit is significant.”

But she’s more worried about what those cuts represent for the overall nonprofit climate.

“Corporations and foundations, if they’ve been cut significantly, are going to have to make up for that, which will also cut into the funding that we would normally receive from those foundations,” she said. “So it’s kind of a trickle-down effect for us in that, yes, the $50,000 is a hit, but we’re more bracing for impact of how (the recession) affects our local foundations and corporations and their level of giving towards us.”

Like the zoo, the farm has taken a big financial hit from canceled fundraising events. “A huge component of our budget, upwards of $400,000, is raised in events that we do every year on the farm, and we are losing that this year,” Storey said. “The only thing I can say is that we’re just bracing ourselves and trying our best to find other ways to get that income in the door. But it’s not easy for anyone at this point. And it’s definitely not easy for the city either!”

As it moves into an uncertain future, JVTF has begun experimenting with new ways of distributing its 24-member team among its educational programming, which has gone virtual this year, and seven farm sites. That’s especially difficult during a year without hundreds of volunteers on hand, like the farm usually has.

“We’re trying out some new models — they may work, they may not — and we’re just going to be very adaptable. Our organization has decided to rise to the challenge, and we’re just going to make it through,” Storey said. “We’ve been able to keep everybody employed since March. We have not made any changes, no pay cuts yet. We’re optimistic. We continue to look for more funding. We continue to show that we’re still here and viable.”

Being a nonprofit director in 2020 means having “to lead and pivot,” Storey said, “and we’re no strangers to this. Oftentimes our community’s most basic needs and necessities are delivered by nonprofit partners, but we’re often the ones most vulnerable when an economic shift happens. … We’re always supposed to be nimble, we’re always supposed to be creative, all of that. This is no different than where a nonprofit sits most times. … We hit the ground running every single day. It’s just now, with a global pandemic, it’s even more challenging, and we just don’t have a lot of answers.”

“Why Has Birmingham Been the Only One Supporting This Anyway?”

“The problem already existed,” said Carlee Sanford. She’s walking along a trail at Ruffner Mountain Nature Preserve, where she’s the executive director. “This pandemic is proving that this whole model in Jefferson County doesn’t work.”

She’s talking specifically about the lack of a countywide park and recreation board, which has left government funding of green spaces such as Ruffner to individual cities, mostly Birmingham. Ruffner, which borders Irondale and is close to Mountain Brook, had its city funding cut from $225,000 to $112,500 in the FY 2021 budget. Other parks also were affected by the cuts; Red Mountain Park went from receiving $100,000 in FY 2020 to nothing this year, while the Railroad Park Foundation’s city funding was cut in half, from $900,000 to $450,000.

“When Mayor Woodfin told me back in June what the proposed cut was, I was like, ‘OK, I understand.’ But my thought has been, ‘Why has Birmingham been the only one supporting this anyway? Why isn’t Mountain Brook helping? Why isn’t Trussville?’”

When Sanford started as Ruffner’s executive director in 2015, more than half of the park’s budget came from the city of Birmingham. Before COVID-19 hit, that number had dropped to roughly 30%, though not because the city was giving less money. In fact, it was giving more. But Sanford also had worked to diversify the park’s funding sources, including building up a base of paying members and enacting a $3 “trail charge” for non-Birmingham residents.

Without city funding this fiscal year, Sanford said, Ruffner has enough money saved to stay open through at least early next year. It will take additional fundraising to keep going beyond that. Sanford said she’s working on negotiating a more substantial rent for three Spire Energy communications towers that were already on the mountain.

But the key for green-space nonprofits such as Ruffner, Sanford suggested, may lie outside of Birmingham. All of Jefferson County’s cities should contribute to their neighboring green spaces, she said — for example, with Mountain Brook, Trussville and Irondale adding to Birmingham’s contribution to Ruffner, or Homewood, Hoover and Vestavia Hills contributing the Red Mountain Park budget.

She’s optimistic that Irondale Mayor-elect James D. Stewart Jr. will be receptive to contributing to the preserve. If that goes through, Sanford hopes other cities in will follow suit.

The private sector should get involved, too. “The other major piece is corporations,” she said. “Something’s got to give there … . We know these corporations benefit from us being here, because their employees are happier. It makes the area better. Having a place like Ruffner is good for their business.”

Overall, “this problem was already obvious,” she said. “And I think the solution right now, with the pandemic, is still the same solution — and it’s bigger than just those places impacted by the city of Birmingham’s budget. We need cities around these parks to start putting in their operational budgets funding for green spaces throughout the county,” she said. “I was telling our board, if we’re just talking about Ruffner, we’re not solving the real problem.”

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.

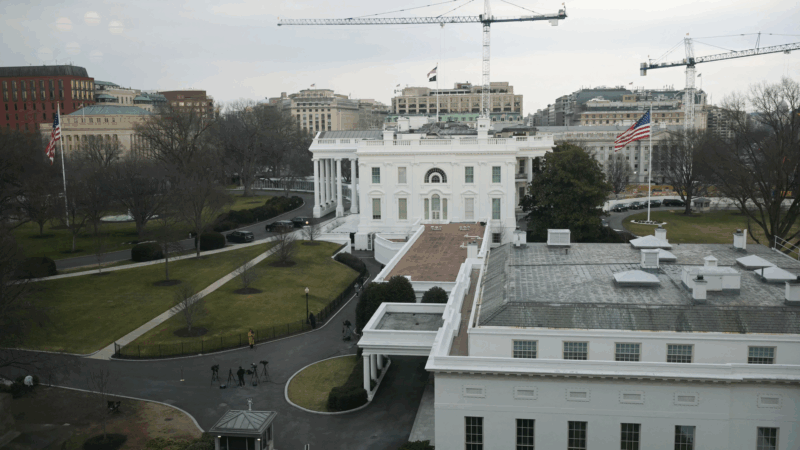

Trump’s ballroom project can continue for now, court says

A US District Judge denied a preservation group's effort to put a pause on construction

NASA lost a lunar spacecraft one day after launch. A new report details what went wrong

Why did a $72 million mission to study water on the moon fail so soon after launch? A new NASA report has the answer.

Columbia student detained by ICE is abruptly released after Mamdani meets with Trump

Hours after the student was taken into custody in her campus apartment, she was released, after New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani expressed concerns about the arrest to President Trump.

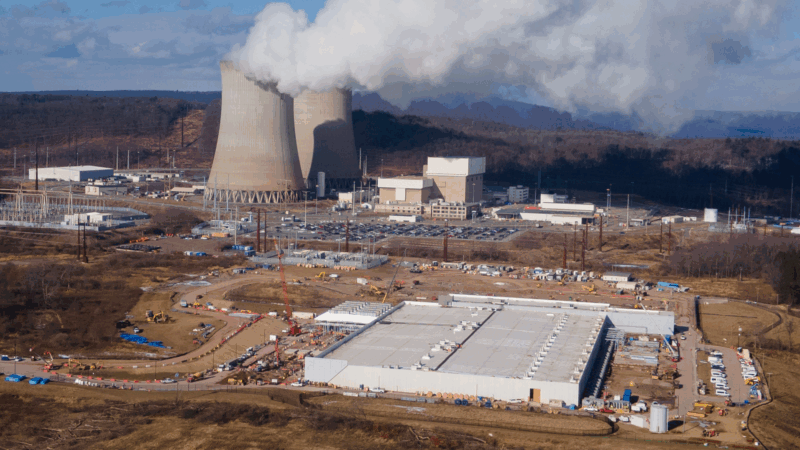

These major issues have brought together Democrats and Republicans in states

Across the country, Republicans and Democrats have found bipartisan agreement on regulating artificial intelligence and data centers. But it's not just big tech aligning the two parties.