New Exhibit At Birmingham Museum of Art Shows American History’s Violent Struggle

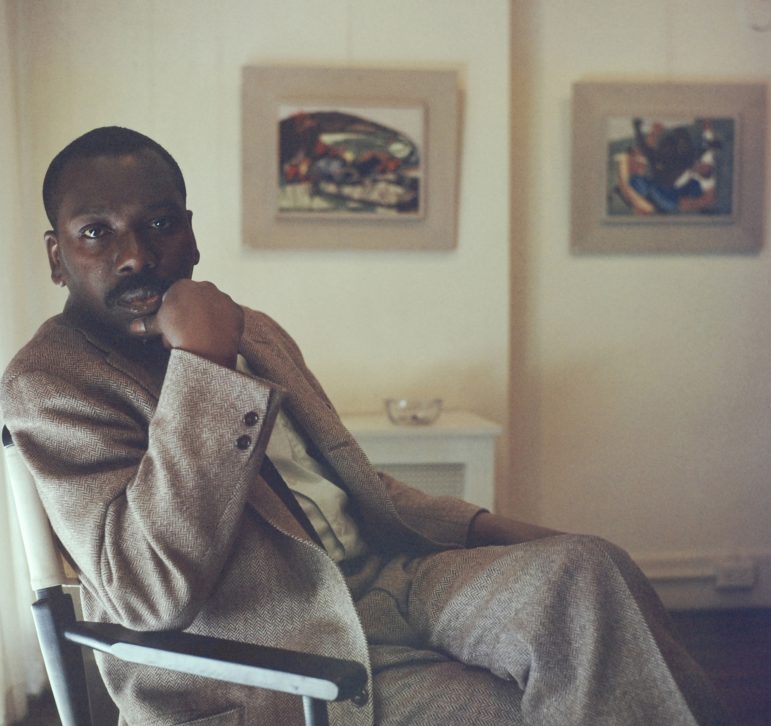

Artists often draw on historical events for inspiration. But American history through the brush of Jacob Lawrence has its own distinctive style. The African American artist is considered one of the great modernist painters of the 20th century. An exhibit featuring his series of paintings “Struggle. . . From the History of the American People” opened Friday at the Birmingham Museum of Art.

Lawrence was born in 1917. The painter came of age in New York City and studied with artists of the Harlem Renaissance. He gained national prominence in his twenties and is best known for collections of paintings that tell a story. His most famous series depicts the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to the North in the early 1900s.

Artist Barbara Earl Thomas was a student of his at the University of Washington in the mid-1970s. They became close, lifelong friends. She knew him for almost 2 years before she realized that Lawrence was a star in the art world.

“I said that you’d been holding out on me. I said you’re famous,” she recalls. “He just smiled and he said, ‘Oh, Barbara.’ And that was that.”

Lawrence was understated and soft-spoken. But he spoke forcefully through his artwork. The powerof the Struggle series practically jumps out of the panels despite their relatively small size.

“They’re really intimate,” says BMA American art curator Katelyn Crawford. “These are panels that, if you took their frames off, could be held in your hands almost like a book.”

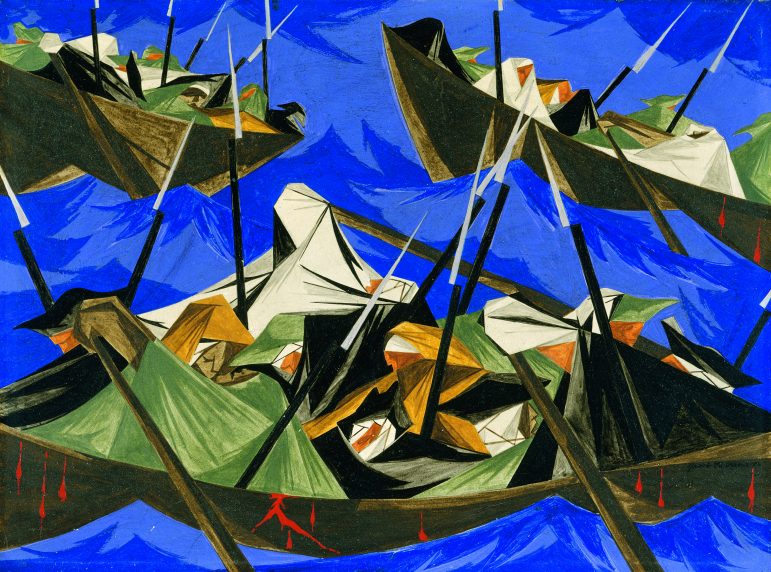

Lawrence’s unique style will grab visitors too. It’s modern art, so the figures are exaggerated and abstract.

“They’re very linear. He’s using hard lines,” Crawford said. “He’s not trying to make his people look like people.”

The angular, geometric figures convey movement. There’s action packed into each scene. Bold, contrasting colors heighten the drama.

Lawrence originally planned 60 panels for this series but produced only 30. They cover the period from the American Revolution to 19th-century westward expansion. While some of his other series are held by museums, this one was broken up and sold soon after it first went on display. It took years to put together the ‘Struggle’ exhibit. Curators had to track down the panels from private collections, and the series may never be shown in its entirety again. Five panels were still missing when the exhibit launched in Massachusetts.

However, when the series was shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, a visitor recognized Lawrence’s style and realized one of the panels might be in a neighbor’s home. The painting’s owner contacted the Met where researchers authenticated the work from the private collection. That lost panel is now part of the Birmingham exhibit.

Lawrence’s historical figures do not look like George Washington triumphantly crossing the Delaware River. Soldiers suffer on Lawrence’s panels, hunkered down in their boats, wrapped up, trying not to freeze.

“We don’t need a George Washington figure,” Crawford said. “You’re in the boat with these individuals and each common person is a protagonist in the creation of the early United States.”

The panels are infused with violence: blood is a common feature.

“It’s a real theme throughout the series and I think you never escape that very literal sense of the struggle,” Crawford said.

Lawrence said he was not trying to paint Black history. He was trying to depict a full picture of American history to include Black people, indigenous people, and others. In a 1988 interview with Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air, Lawrence said he was motivated to create compelling art.

“I did them out of sheer drama and out of being able to relate to the content. That was my purpose with doing them,” Lawrence said.

Lawrence created this series in the mid-1950s, during the civil rights struggle. Artist Barbara Earl Thomas says that Lawrence’s work is important today because it forces the audience to wrestle with our shared, troubled history at a time of racial reckoning.

“I think that is now our job, for us to together figure out what we’re all losing by not looking straight into the eyes of the beast that we’ve created together,” Thomas said.

The exhibit runs at the Birmingham Museum of Art through February 7. The museum is a program sponsor of WBHM, but our news and business departments operate independently.

Senate Democrats ramp up pressure campaign for public hearings on war with Iran

Congressional Democrats are demanding transparency in the form of public hearings from Trump administration officials on the timeline and objectives of the war in Iran.

Ivey commutes death sentence of inmate whose accomplice fired fatal shot

Charles “Sonny” Burton was sentenced to death for the killing of Doug Battle during a 1991 robbery. However, another man shot Battle when Burton had left the building.

Wheelchair curler Steve Emt’s path from drunk driver to three-time Paralympian

Steve Emt and Laura Dwyer represent the U.S. in the Paralympics' new mixed doubles wheelchair curling event. They could bring home Team USA's first wheelchair curling medal ever.

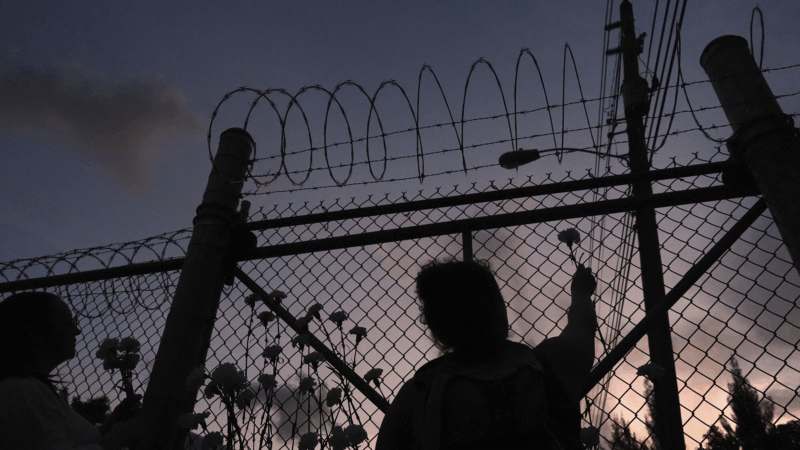

Immigration detention on track for deadliest fiscal year since 2004

Twenty-three people have died since October in ICE custody, as advocates warn about overcrowding and health care access.

Photos from Iran and across the Middle East as the war enters Week 2

More than a week of the U.S. and Israel's war against Iran has dragged in global powers, upended the world's energy and transport sectors, and brought chaos to usually peaceful areas of the region.

‘American Classic’ is a hidden gem that gets even better as it goes

In this charming TV series, Kevin Kline plays a Shakespearean actor who retreats to his small hometown after a crisis, and gets engaged in an effort to save the local theater.