COVID-19 Crisis Threatens To Bankrupt And Close Struggling Hospitals In The Rural South

“Eerily quiet” is how one doctor described the non-emergency wings of the hospital they work at in rural Louisiana.

Due to COVID-19 crisis restrictions, there’s hardly anyone lingering in the public-facing spaces, like the cafeteria, gift shop, and main lobby. But when you go up to the ER, they said, it’s another world.

“You go to a floor, every single patient room is filled,” they said. “You go to an ICU: all you hear are people coding and losing pulses. You hear people running all over. There’s ventilators buzzing everywhere… I mean, it’s total chaos.”

This doctor practices emergency medicine at the hospital. They’re not allowed to talk to the media and fear retribution for doing so, so New Orleans Public Radio is not using their first or last name, though their identity was verified. Doctors in Mississippi and elsewhere have been fired for speaking with the press.

For hospitals in rural areas like the Deep South, the COVID-19 crisis is not only threatening to overwhelm ICUs with patients seeking treatment. It could also force many of them to close.

The problem lies alongside the “eerily quiet” wings.

Ryan Kelly, executive director of both the Mississippi Rural Health Association and the Alabama Rural Health Association, said closing rural hospitals is his greatest concern.

“Not because of anything that’s their fault,” he said, “but because we have a shutdown right now and they make most of their money off of stuff that they’re not actually able to do.”

States across the country have banned elective procedures, like hip replacement surgeries and physical therapy, to make sure hospitals have enough staff and personal protective equipment (PPE) to handle a surge of COVID-19 patients.

The trouble is, Kelly said, in our current healthcare system, those procedures account for the bulk of the revenue that rural hospitals pull in.

“If your hospital makes 75% of its money off of these outpatient programs that are now almost nonexistent, I mean, it’s not a death by a thousand cuts. It’s death by a thousand, you know, gunshots now,” Kelly said. “I mean, they are bleeding very, very fast.”

Financially speaking, rural hospitals have been skating on thin ice for years.

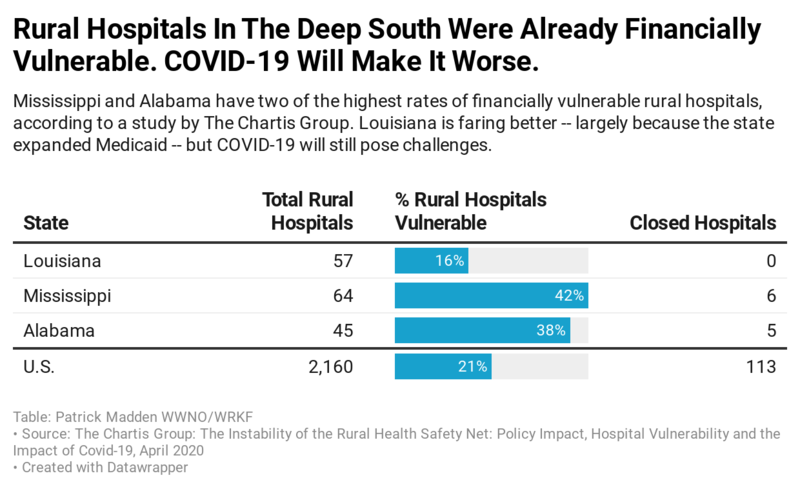

According to a recent report from the healthcare consulting company Chartis Group, more than 100 rural hospitals have closed since 2010. A whopping 453 — roughly a quarter of all rural hospitals identified in the report — are at risk of closing right now.

Dr. Roger Ray, physician consulting director with The Chartis Group, said the COVID-19 crisis is hurting hospitals everywhere, from big cities to small towns. The difference is that urban hospitals tend to have more money in the bank: up to 400 days of cash on-hand.

Before the pandemic, Ray said, rural hospitals typically had about 30 days worth, “And for some, it was single digits.”

According to the Chartis report, several southern states have a high percentage of rural hospitals at risk of closing. Louisiana is in the best shape: 16 percent of its rural hospitals are vulnerable. In Alabama: 38 percent.

Mississippi is most at risk, with 42 percent of its rural hospitals vulnerable to closing.

But right now, rural hospitals need more, not less.

For the last several weeks, most of the patients coming through this emergency room have been treated for COVID-19, and caring for them is demanding, stressful work.

COVID patients can become severely ill in a matter of hours, needing constant attention. Treatment plans are not always clear and hospital space is increasingly tight. Physical touch is limited and empathetic smiles from healthcare workers are all but lost under layers of protective equipment. People die alone.

All of that takes a toll on healthcare providers. One veteran nurse practitioner who works at the hospital, and who also requested anonymity, has struggled for the first time to transition between work and home life.

“I’ve never come home from work on a daily basis and had to sit outside to get myself together — to try and find some sanity and cry,” they said. “Never.”

After an emergency room shift, their only respite is sitting in a lawn chair, silently watching cars drive by for a half-hour, “because that’s how high the level of stress is at work.”

Rural communities are particularly vulnerable to the novel coronavirus. Their residents tend to be older and have more underlying health conditions than the wider population. But this Louisiana hospital isn’t adding staff to meet the crisis head-on, it’s reducing emergency room staff.

“You don’t cut hours in the midst of a pandemic,” the nurse practitioner said. “Not being able to provide care for someone that needs it … all over a bottom line — money — is extremely frustrating.”

Help is on the way. There’s no telling if it’ll be enough.

Last month, Congress passed the CARES Act, which is sending $1,200 stimulus checks to most Americans. That bill also includes a $100 billion cash infusion specifically reserved for hospitals across the country. Essentially, bags of cash to keep their doors open.

Ryan Kelly, of the Mississippi and Alabama Rural Health Associations, said that will be a big help for rural hospitals. But the question is how long that money will last.

Based on conversations with hospital administrators and a general sense of rural hospital margins, Kelly said, “we’re in deep trouble” if restrictions on elective procedures continue through May.

The future feels distant and unknowable for the Louisiana nurse practitioner. They have a hard time imagining when they might, once and for all, be able to hug and kiss their family and friends again.

“I’m from South Louisiana, that’s what we do,” they said. “There’s no, like, ‘hey’ from a distance. You gotta give a hug.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Birmingham, Alabama, WWNO in New Orleans and NPR.

Bill making the Public Service Commission an appointed board is dead for the session

Usually when discussing legislative action, the focus is on what's moving forward. But plenty of bills in a legislature stall or even die. Leaders in the Alabama legislature say a bill involving the Public Service Commission is dead for the session. We get details on that from Todd Stacy, host of Capitol Journal on Alabama Public Television.

My doctor keeps focusing on my weight. What other health metrics matter more?

Our Real Talk with a Doc columnist explains how to push back if your doctor's obsessed with weight loss. And what other health metrics matter more instead.

Baz Luhrmann will make you fall in love with Elvis Presley

The new movie is made up of footage originally shot in the early 1970s, which Luhrmann found in storage in a Kansas salt mine.

Forget the State of the Union. What’s the state of your quiz score?

What's the state of your union, quiz-wise? Find out!

A team of midlife cheerleaders in Ukraine refuses to let war defeat them

Ukrainian women in their 50s and 60s say they've embraced cheerleading as a way to cope with the extreme stress and anxiety of four years of Russia's full-scale invasion.

As the U.S. celebrates its 250th birthday, many Latinos question whether they belong

Many U.S.-born Latinos feel afraid and anxious amid the political rhetoric. Still, others wouldn't miss celebrating their country