The 15-Year Fight to Integrate Public Schools

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education struck down racial segregation in schools. While the court ordered public schools to desegregate “with all deliberate speed,” the vague language allowed Southern officials to delay and resist school integration for years.

It wasn’t until 1969 that the court forced school integration in a case called Alexander v. Holmes. Birmingham-Southern College history professor Will Hustwit wrote about the case in his book, “Integration Now: Alexander v. Holmes and the End of Jim Crow Education.”

“Litigation Forever”

Hustwit says the Brown ruling sparked years of resistance from Southern leaders. In Virginia, the governor shut down three public school systems to avoid integrating. Alabama banned the NAACP for a time. But more generally, politicians and communities dragged their feet delaying progress on the issue.

Some black students did enter formerly white schools under “freedom of choice” policies which allowed parents to choose where they wanted their children to attend school. “That was something the civil rights lawyers wanted initially. They thought that that was empowering to black communities,” Hustwit says.

But in practice, social pressure and threats kept many black families from enrolling their children in formerly white schools. Freedom of choice resulted in mostly token integration. “The thing about token integration was that it effectively became the main way segregationists could keep segregation,” Hustwit says.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court put the responsibility of oversight of school integration on federal district judges, leaving some reluctant or segregationist judges in the South to supervise the process.

“[Those judges] had a lot of authority according to the Brown ruling and the implementation to slow down, check, refuse to cooperate with the federal courts higher up and especially with the civil rights lawyers,” Hustwit says. He says Harold Cox, a federal judge in Jackson, Mississippi, was particularly clever about limiting school desegregation in the 1960s.

Mississippi-born

Alexander v. Holmes had its origins in Holmes County, Mississippi, a rural, agricultural area north of Jackson. Hustwit says that county had a particularly strong black activist community that put a lot of work into voting rights efforts. After that, they turned to integrating schools. “Incredibly, there’s something like 300 or 400 black students who are enrolled in Holmes County in 1965,” Hustwit says.

That year black families sued Holmes County schools saying leaders were resisting desegregation. The case eventually made it to the Supreme Court in October 1969. About a week later, the justices issued a unanimous ruling saying schools had to integrate immediately. The ruling came despite some debate among the judges behind the scenes.

The main issue was how much time to give schools to integrate. After all, this was in the middle of a school year. “Justice [Hugo] Black [of Alabama] is the one who is really adamant about saying we’re going to do this,” Hustwit says. “They’ve had all the time to do this. It’s been 15 years. Let’s do this thing.”

There were concerns about adequate transportation and facilities. Schools also had to make sure hiring practices for teachers and administrators were equitable. “But basically in January 1970…school districts get into line and start doing this,” Hustwit says.

The Ruling’s Legacy

Hustwit says the decision is a momentous change and represents the culmination of years of sometimes dangerous work by civil rights groups to integrate schools. He adds the ruling should be judged by what it meant at the time. Hustwit points out that 100 years earlier blacks were setting up the first public schools in the South during the Reconstruction Era, although they were not integrated. Before that, it was illegal to educate blacks.

“If you kind of put it into that long arc…then that’s where I think the case’s true significance comes out,” Hustwit says.

The ruling is still in effect, but 50 years later some schools have re-segregated, with some suburban districts overwhelmingly white and urban districts overwhelmingly minority. It’s not segregation by law, but de facto segregation. Hustwit says part of that is due to a significant increase in new private schools, sometimes termed “segregation academies,” as well as breakaway school districts.

Many school systems in Jefferson County broke off on the years since the ruling. The most recent attempt was by Gardendale. Those behind the push said the move was not about race, but rather about local control and accountability. In 2017, a federal judge found race was a motivating factor, but allowed the separation to go ahead under certain conditions. The city abandoned the effort after an appellate court reversed the ruling.

“Those are ongoing issues that we have today,” Hustwit says. He suggests any resolution will come at the local level. “You can have orders from federal courts. You can have mandates from the federal government. Whether or not a local community decides that this is something that’s important to them is a different matter.”

Photo by the U.S. Department of Education

Trump says he is ‘not happy’ with the Iran nuclear talks but indicates he’ll give them more time

U.S. President Donald Trump said Friday he's "not happy" with the latest talks over Iran's nuclear program but indicated he would give negotiators more time to reach a deal to avert another war in the Middle East.

Bill Clinton says he ‘did nothing wrong’ with Epstein as he faced grilling over their relationship

Former President Bill Clinton told members of Congress on Friday that he "did nothing wrong" in his relationship with Jeffrey Epstein and saw no signs of Epstein's sexual abuse as he faced hours of grilling from lawmakers over his connections to the disgraced financier from more than two decades ago.

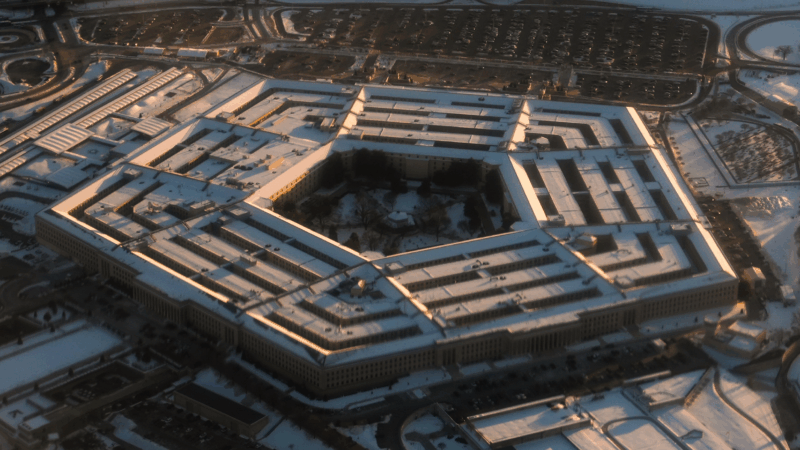

Pentagon puts Scouts ‘on notice’ over DEI and girl-centered policies

After threatening to sever ties with the organization formerly known as the Boy Scouts, Defense Secretary Hegseth announced a 6-month reprieve

President Trump bans Anthropic from use in government systems

Trump called the AI lab a "RADICAL LEFT, WOKE COMPANY" in a social media post. The Pentagon also ordered all military contractors to stop doing business with Anthropic.

HUD proposes time limits and work requirements for rental aid

The rule would allow housing agencies and landlords to impose such requirements "to encourage self-sufficiency." Critics say most who can work already do, but their wages are low.

Paramount and Warner Bros’ deal is about merging studios, and a whole lot more

The nearly $111 billion marriage would unite Paramount and Warner film studios, streamers and television properties — including CNN — under the control of the wealthy Ellison family.