With Low-Impact Development, Cities Hope to Better Control Runoff

Stormwater runoff is what washes off of parking lots, roadways and rooftops when it rains. Eve Brantley, associate professor of crop, soil and environmental sciences at Auburn University, says it may sound harmless, but it has a big impact.

“I just feel like it’s the forgotten pollution,” Brantley says.

She says part of the problem is that stormwater picks up other pollutants like trash and fertilizer. The other issue is the sheer volume of runoff that is discharged into area waterways.

Cahaba Riverkeeper David Butler sees the impact on a daily basis.

“So we’re pushing so much water into the river so fast now that, you know when it rains, instead of soaking into the ground, it’s all channeled to the river,” Butler says. “So it rises really quick, falls really quick, and you get a lot more erosion like this.”

He says all along the river, large sections of the bank have collapsed, often during rainstorms. This strips away vegetation that normally acts as a buffer, leaving dirt to erode into the river and fill it with sediment.

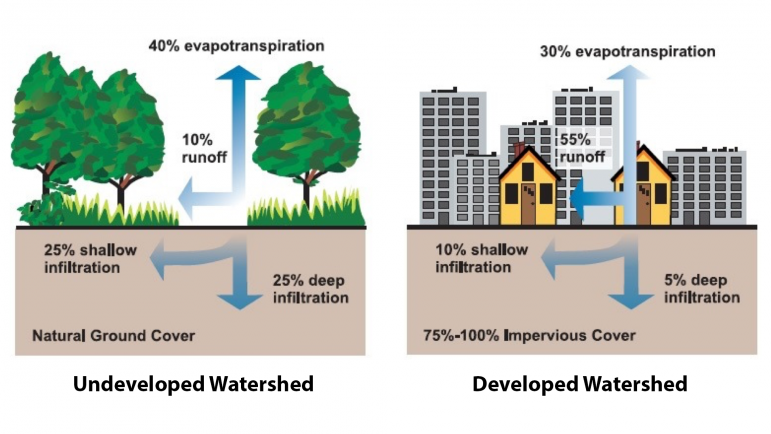

Stormwater runoff is an issue in cities throughout the U.S. Experts say developers have paved over so much land that they have changed the balance of the watershed. Now, when it rains, it’s more likely to flood; during a drought, there is less groundwater to recharge rivers and lakes.

That has gotten the attention of local residents and city leaders. At a city council meeting earlier this year, Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin said developers need to be proactive.

“I like plain language. We live in a bowl. And that’s caused a lot of problems for our residents,” Woodfin says. “We gotta make sure for any new development, that it doesn’t add on to the hurt that our residents are already facing.”

The council later approved an ordinance to encourage low-impact development. Several surrounding cities have done the same, following new requirements for municipal stormwater permits issued by the Alabama Department of Environmental Management.

According to Randy Haddock, field director of the Cahaba River Society, the idea behind low-impact development (LID) is to better control runoff.

“There are a number of techniques called these green infrastructure and low-impact development techniques that allow a builder to minimize those stormwater impacts by encouraging water to soak into the ground,” Haddock says, “as opposed to putting it in a pipe and very deliberately putting it in the storm drain right away.”

You may have seen some of these features around Birmingham. Railroad Park has a lot of them built into the landscape. Some common approaches to LID include impervious surfaces to allow filtration, rain gardens or bioswales, and preservation of original vegetation.

Civil engineer Chad Bowman helped incorporate some of these elements into the Crowne at Cahaba River apartments, which sit adjacent to the Cahaba just off of U.S. 280. From the edge of the parking lot, Bowman points out the low-impact features, such as shallow basins full of gravel surrounded by bushes and grass. He says there is a strategic underground system to control stormwater runoff.

“All the water from this area runs down and goes underneath in pipes under here and then it discharges into this, what I’d say is a constructed wetland,” Bowman says.

He points below to a vegetated area full of cat tails that catches the runoff from the apartment complex.

“So what you’re getting is filtering of all this roof water and parking lot water in this little pond.”

That means water has time to soak into the ground and get rid of contaminants like oil and fertilizer, before slowly draining into nearby streams and rivers.

Bowman says features like these will likely be more common in the future, in part because cities are making them more of a priority. There is also increased demand from property owners and residents who want the added benefits of low-impact development, like green space, walkability, and flood control.

Randy Haddock of the Cahaba River Society says cities are making progress.

“It is better,” he says. “They’re beginning to be certain that developers and builders know that this is something that should be addressed.”

But Haddock says it is a little late. Much of Birmingham has already been developed, and he says to retrofit an existing stormwater system is about 10 times as expensive as it is to get it right the first time.

Editor’s Note: The Cahaba River Society is a member sponsor of WBHM, but our business and news departments operate separately.

U.K. leader’s chief of staff quits over hiring of Epstein friend as U.S. ambassador

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer's chief of staff resigned Sunday over the furor surrounding the appointment of Peter Mandelson as U.K. ambassador to the U.S. despite his ties to Jeffrey Epstein.

Trump administration lauds plastic surgeons’ statement on trans surgery for minors

A patient who came to regret the top surgery she got as a teen won a $2 million malpractice suit. Then, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons clarified its position that surgery is not recommended for transgender minors.

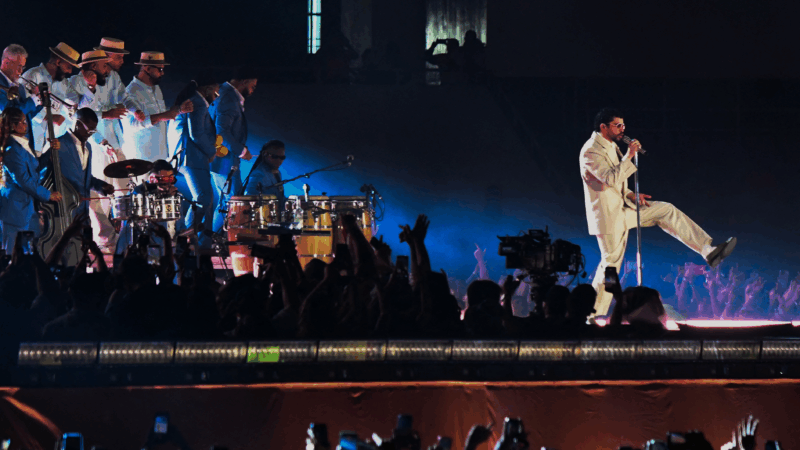

What you should know about Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show

Will the Puerto Rican superstar bring out any special guests? Will there be controversy? Here's what you should know about what could be the most significant concert of the year.

Sunday Puzzle: -IUM Pandemonium

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with KPBS listener Anthony Baio and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

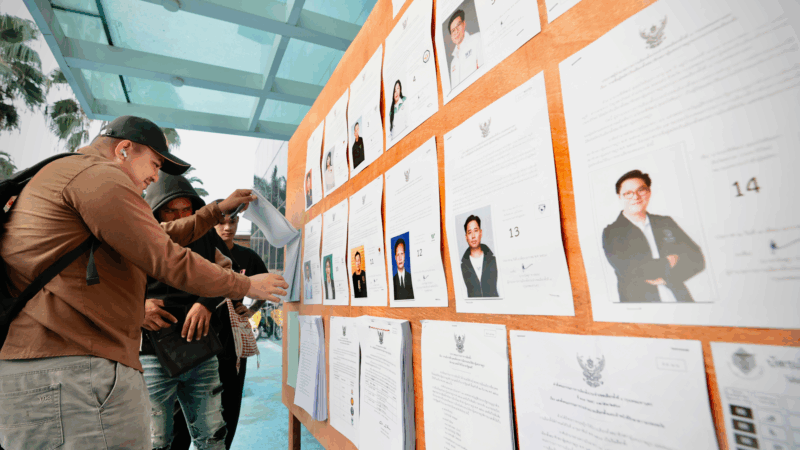

Thailand counts votes in early election with 3 main parties vying for power

Vote counting was underway in Thailand's early general election on Sunday, seen as a three-way race among competing visions of progressive, populist and old-fashioned patronage politics.

US ski star Lindsey Vonn crashes in Olympic downhill race

In an explosive crash near the top of the downhill course in Cortina, Vonn landed a jump perpendicular to the slope and tumbled to a stop shortly below.