Helping Walker County Families Destroyed by the Opioid Crisis

By Whitney Sides

Not long ago, more than 66 million pain pills flowed through Walker County, a rural area 15 miles northwest of Birmingham.

The county was particularly hard hit from 2006 to 2012. During that period, data released by the Washington Post showed that overprescribing of opioids grew to the point that there was enough for every person in the county to have about 150 pain pills, whether they needed them or not. Officials called it a public health crisis.

Today, the children of those who struggled with addiction still feel the effects, and people in the county are forging a new path to help rebuild families.

Paige Britton, a mother of four in Walker County, spent nearly a decade addicted to opioids and started selling pills to support her habit. Eventually, she ended up in jail and lost custody of her kids.

“After I had my first child, I started experiencing postpartum depression. And I started self-medicating to numb that,” Britton says.

She’s been sober for five years. Now, she’s a peer recovery specialist with ROSS, a recovery outreach group in Walker and nearby Winston counties.

ROSS Outreach is staffed by people who have battled addiction themselves, helping find resources for those struggling with substance use issues. But that’s no small task.

There are no inpatient treatment facilities nearby, so Britton drives clients to doctor appointments in Birmingham or wherever there’s an open bed.

She says she also spends a lot of time thinking about how many children are growing up without their parents.

“We’re trying to figure out what we can do in the county to meet those needs and help these children,” she says.

Barry Spear, a spokesman for the Alabama Department of Human Resources, calls it a generational drug problem.

“We know there’s been an uptick in children brought into care because of substance abuse,” Spear says. “It’s close to half of the children that come into care.”

There are about 215 children in Alabama Department of Human Resources (DHR) custody in Walker County. Many of those cases are directly related to the opioid crisis.

Spear adds that rural counties grapple with drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine more than cities like Birmingham and Mobile. At the same time, addiction specialists are hard to come by in rural areas.

That’s changing in Walker County, where several nonprofits offer support groups, parenting classes and childcare for families affected by the opioid epidemic. One of them is Jasper Area Family Services Center.

Donna Kilgore, the center’s director, was a social worker and addiction counselor for over 30 years. She says her biggest struggle is the stigma around addiction. That includes a significant number of grandparents who have become full-time caregivers.

“Particularly if you’re the grandparent being the parent, it’s probably because of some stressful event in your life,” Kilgore says.

Having people to talk to and being around others who have faced similar challenges can help, she says.

The focus has also shifted to children as awareness has increased over the last decade.

Rachel Puckett, who works at Capstone Rural Health Center in Parrish, says there are now more ways to identify children dealing with substance abuse in their families.

One program in Jasper trains teachers and principals to spot the signs of trauma, such as lashing out at school. Puckett says in the past, children would be disciplined for such behavior. But she says that makes it even harder on kids who are dealing with chaos at home. Instead, teachers are taught to approach each situation with empathy.

“Some of the work we’re doing now will make it so that there are more helpers in the community to be responsive when people ask for help,” Puckett says.

Puckett works with a group of nonprofits and organizations including the United Way, Capstone Rural Health Center, and the Walker Area Community Foundation.

The consortium recently raised more than a million dollars worth of grant money and state assistance for opioid abuse services and prevention in Walker County. The influx of money and services provide the county a lifeline, including a network of helpers to plug in those who want to help but had no idea where to begin.

Puckett says harnessing the power of people is the community’s biggest weapon against the lasting effects of opioid abuse.

Those seeking help for substance abuse disorder and recovery in Walker County are encouraged to call the 24/7 Helpline to connect with local counselors and resources at 844-307-1760.

Photo Source: GeoTrinity

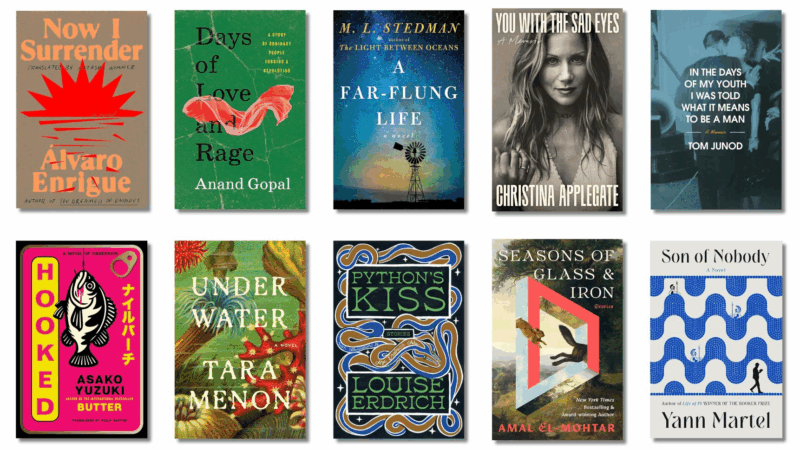

10 new books in March offer mental vacations

March is always a big one for books – this year is no different. We call out a handful of upcoming titles for readers to put on their radars — offering a good alternative to doomscrolling.

Sen. Chris Coons, D-Del., talks about the war with Iran and upcoming war powers vote

NPR's A Martínez asks Delaware Democrat Chris Coons, a member of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, about the war with Iran.

The candy heir vs. chocolate skimpflation

The grandson of the Reese's Peanut Butter Cups creator has launched a campaign against The Hershey Company, which owns the Reese's brand. He wants them to stop skimping on ingredients.

Scientists make a pocket-sized AI brain with help from monkey neurons

A new study suggests AI systems could be a lot more efficient. Researchers were able to shrink an AI vision model to 1/1000th of its original size.

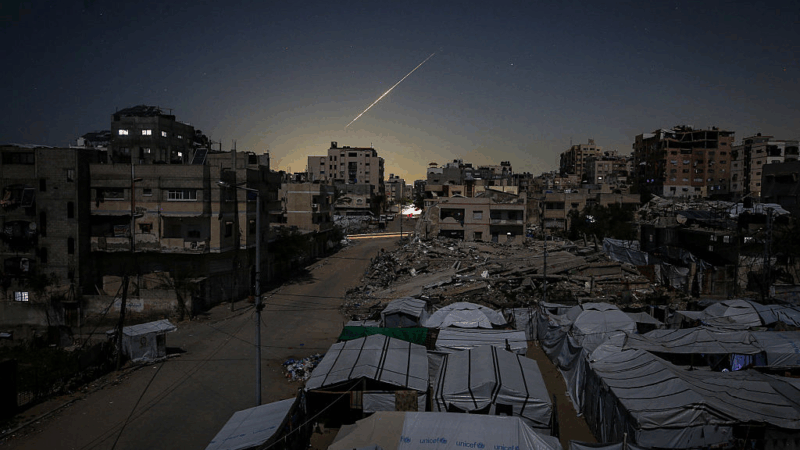

U.S. evacuates diplomats, shuts down some embassies as war enters fourth day

The United States evacuated diplomats across the Middle East and shut down some embassies as war with Iran intensified Tuesday while President Trump signaled the conflict could turn into extended war.

Kristi Noem set to face senators over DHS shutdown, immigration enforcement

The focus of the hearing is likely to be on how Kristi Noem is pursuing President Trump's mass deportation efforts in his second term, after two U.S. citizens were killed by immigration officers.