Cloudy Future for Dauphin Island, a Canary in the Coal Mine of Climate Change

By Hank Black

Along coastal Alabama lies Dauphin Island, a narrow, shifting strip of sand inhabited by a laid-back vacation town that is becoming more endangered with every passing storm and every incremental rise in the warming waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

Dauphin is one of perhaps 2,200 barrier islands that make up 10% to 12% of the globe’s coastline. They help absorb the blows of nature and suffer greatly for it, either eroding dramatically from catastrophic hurricane forces or gradually, almost imperceptibly, from constant wave action.

These sandy, offshore bodies are potent poster children for our planet’s warming, part of a natural, 100,000-year cycle that, according to most scientists, has greatly accelerated since the birth of the Industrial Age.

That transformative age was and largely continues to be powered by the burning of carbon-based fuels, principally coal. Almost 60 percent of emissions from such fossil fuels remain in the atmosphere and is largely responsible for global warming. That coal is to blame lends irony to the view that fragile Dauphin Island is a canary in the coal mine of climate change.

No doubt there remains a veneer of resistance to this scientific consensus – few political leaders of red-state Alabama voice agreement with the voice of science on this matter. Yet, on Dauphin Island, realpolitik is at work as the town begins to consider how to respond to the question of its own survival.

A Little History

The armor of natural sand dunes and the stands of slash pine trees that anchored the dunes once kept the island from being blown away by seas and wind, and the small population could hunker down and absorb the blows of nature. That changed almost a century ago, when money men from Mobile began to envision the undeveloped property as a close-at-hand family getaway site.

The chamber of commerce persuaded the islanders to sell much of the island, sealing the deal with the promise to build it a bridge to the southwestern tip of Mobile Bay. Developers quickly leveled the dunes and cut wide swaths of the deep-rooted pines to erect vacation homes with majestic views of the water.

The island’s ecologic fabric was always under threat from natural forces, but once the dunes and trees were destroyed and warmer atmosphere and seas spewed forth with more intense wind and rains, it became more susceptible to being torn to pieces.

In the years since, Dauphin Island reaped the whirlwind, as one strong storm after another blew away houses and even the bridge, and the sea surged over the sand, reshaping the island time and again and migrating it toward the coast. But beach houses and bridge were quickly replaced as sand and sun worshippers continued to flock to the coastal paradise.

And if the island were ever cut in two by a hurricane, the federal government engineers could be counted on to replace the sand and bring back the vacationers for the next summer season.

Yet, erosion and sea level rise continue to take their toll on Dauphin Island, where land mass has decreased by 16 percent over the past 50 years. Ken Heck, director of the Dauphin Island Sea Lab, estimates the shoreline has moved back as much as a meter in just the past five years. He predicted that in 30 to 40 years, the island’s low-lying and dune-less western half would be under water.

“We don’t know how this will turn out,” Heck said. “Things are different now, in the speed of change and in the fact that more people are living where change will matter most.” Those people, he added, are at risk of “losing their nest egg.”

A Great Place to Live

In summers, Dauphin Island’s population of 1,300 residents grows by a factor of five or six, including day-trippers. Some families have lived there for generations. Jeff Collier’s is one. He recounts it was a great place to grow up, kind of like country living, without the rowdy crowds and jammed-together high-rise traffic, condos, casinos and hotels that eventually came to characterize the Gulf coastline from Biloxi to Gulf Shores to Destin.

The developers, who destroyed the dunes and tree stands, were restrained from building higher than 85 feet on the island. Collier, who’s been either a town councilman or, as now, mayor since the town’s incorporation in 1988, said folks have been fiercely guarding against encroachment of spring-fling-style vacationing.

But, he said, it’s become more apparent that you can’t necessarily stand pat against the forces of nature. A lifetime of large and small storms that require pushing sand off the roads time and again, of seeing water and sewer systems overcome, grand properties go underwater, and the island’s western end moving back and forth like a dog’s tail – all that was difficult but seemed manageable.

Manageable, that is, with the expectation that FEMA and the Army Corps of Engineers would make it right if a hurricane’s storm surge scoured the beaches. The feds paid 80 percent of the cost of restoration – up to $200 million over the years by some estimates. Depending on the severity of a hurricane, Collier said, recovery costs range from $3 million to $8 million.

Manageable, that is, until Collier and others realized that what once took a tropical storm or hurricane to cause major devastation might now only take an unremarkable event, perhaps coupled with a high tide, like Category 1 Hurricane Barry earlier this year.

Michael Clemmer

Dauphin Island Mayor Jeff Collier ponders the fate of Dauphin Island as the climate causes changes. “There are not a lot of good answers or a lot of cheap answers,” he says.

Cutting the pine trees to build homes became a tipping point for the town this year. “In the last four or five years we’ve seen a tremendous uptick in residential development that’s having an effect on the forested (eastern) end of the island,” the mayor said. Fewer trees mean less stable soil, less protection from high winds and less habitat at the 126-acre Audubon Bird Sanctuary, a major tourist attraction.

“The size of lots is relatively small,” he explained, “and property owners want to make room for bigger houses, and you end up with clear-cutting.” So, in August, the town council, with one abstention, ordained that removal of trees would be allowed only within a 5-foot perimeter around new structures.

“That was part of trying to balance private property rights with trying to be good environmental stewards,” Collier said.

Property rights sometimes are trumped by ecological forces, of course. On the western end of the island, about 60 properties have been swallowed by the sea (and lost to the town’s tax rolls) over the years. Fully or nearly submerged pilings are stark reminders of someone’s summer home or beach vacation. “You stand in front of one beach house and there’s another parcel ahead that somebody else owns that’s 6 to 8 feet underwater as the west island migrates.” Collier said.

Long-Term Survival

The long-term survival of the island town now weighs heavily on Collier.

“People might lose their property in the next several decades,” he said. “Climate change and sea level rise are major threats that right now don’t have a whole lot of good answers. People have different opinions about it. I mean, who wants to deal with that type of problem?”

He’s not an alarmist, “but you have to be aware, and I’d be foolish as an elected official to just discount what’s happening. The problem is, there are not a lot of good answers or a lot of cheap answers.”

That cost conundrum may best be illustrated by the expense of restoring the island’s beaches. After past disasters, such as when Hurricane Katrina cut Dauphin Island in half, FEMA and the Corps of Engineers dredged sand and replenished what was lost. And property owners relied on their insurance to help rebuild structures. A question is how long taxpayers and insurance companies will tolerate such outlays, especially as more significant low-lying metropolises – think Miami, New York City and Boston – will require exponentially more money to protect?

An Existential Conundrum

“There may be some things that we absolutely can’t do something about,” Collier said. “When it comes down to resources and abilities, it may be that we can’t totally fix all of this stuff.”

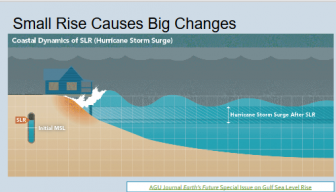

The vulnerability of the island has increased in recent years, Collier said. “We’re having storm events more often, and it takes less of a storm to create a problem these days. We’re less resilient – I jokingly say some parts flood in a heavy dew – and it takes less tidal rise, less wave action and wind to push sand and salt water into areas we have to clean up, when that wouldn’t have happened 10 years ago. Storm surge can create more problems, and more problems means more cost to the community,” Collier said.

The town and its utility systems have a challenge keeping roads in place and drainage and driveways cleared. The water and sewer utility, separately operated, must deal with saltwater and sand that has to be pumped out when they inundate the systems, and constant repair of the lines. Hurricane Barry, that “nothing” storm, pushed almost five feet of sand over side streets on the west end and only a little less on Bienville Boulevard itself.

And, he said, “The people are looking for normalcy of roadways, parking areas, water, sewer, electricity – all these things – in an arena that is not normal,” he said.

Frictions arise among beachgoers in this environment, as well. Wind and waves have reduced the amount of beach available to property owners. More people are crowding into a smaller beach space, and vacationers who have rented high-dollar houses feel invaded. “You go down the steps to the beach and there are already six or seven people sitting out there, so you get into this ‘elbowing’ effect,” Collier said.

Michael Clemmer

Some owners have constructed seawalls as they try to keep their properties from being lost to the rising Gulf waters, but the walls cause extreme erosion on both sides that threatens the structures behind. With the buildings isolated on seawall peninsulas, a high tide coupled with a significant storm surge would cause major damage. Several dozen structures have been abandoned to the sea, and some predict the island’s entire western end will be underwater within four decades.

When erosion actually undercuts a residence and the water threatens power, water and sewer supply, the owner might purchase another lot. Or they could move the structure farther from the beach on the same property; the town has reduced set-back requirements to allow buildings to be moved or built closer to Bienville Boulevard, which bisects the length of the island. The most recent couple of houses that had to be moved were on the east end of the island, a reminder that sea level rise affects the entire periphery.

Condemnation for safety reasons is the third option. It’s not done lightly, perhaps eight times in the past several years, Collier said, but when pilings are not deep enough or essential utilities can’t be connected, buildings are deemed unsafe for habitation.

A Retreat Begins

What is the town’s response to its existential problem? It’s a comprehensive plan to retreat to higher ground on the eastern side, where taking measures of resiliency can prolong its survival. The heaviest losses will be on the west end, where miles of rental homes line the beaches and, through a stiff lodging tax, support most of the town budget of little more than $3 million.

Planned retreat such as this is increasingly seen as the way forward for coastal communities. A recent article in Science noted that forces against retreat are numerous: short-term economic benefits of development; subsidized insurance rates and disaster recovery costs; different incentives among residents and local and national officials; imperfect perceptions of risk; attachment to place; and clinging to the status quo. But in Louisiana, an entire town permanently evacuated before it went underwater, and in Canada, residents of a frequently flooded town were bought out because of the cost of repeatedly restoring it. Government attitudes are beginning to shift in that direction.

To replace the revenue, Dauphin Island seeks to focus more economic development on its east end, further from the hazard zone. Using funds stemming from the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the town plans to develop the business district at Aloe Bay on the more protected Mississippi Sound side of the island. Collier envisions a river walk with shops that could provide economic sustainability without sacrificing the small-town atmosphere that he said makes Dauphin Island more attractive than the “concrete jungles” on the coast.

“We took an approach that we need to do things differently, take a look at more sustainable parts of the island and put those to the best use for the long-term survivability of the community,” Collier said.

Asked what the island would look like by mid-century, he said, “We’ll have lost additional private property, shorelines will have receded further, and the same impacts will continue. It even gets to the point of thinking about access to the island – the roadway may have to be elevated.”

Over the next year, BirminghamWatch will visit places in Alabama where ways of life have been affected as climate changes and look at what’s being done to mitigate or avoid the effects. This is the second in a series of four stories from Alabama’s Gulf Coast. Read the first story, Changing Climate: Alabama Sees Heat, Storms, Drought and Turtles

Trump warns Iran not to retaliate after Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed

The Iranian government has announced 40 days of mourning. The country's supreme leader was killed following an attack launched by the U.S. and Israel on Saturday against Iran.

Iran fires missiles at Israel and Gulf states after U.S.-Israeli strike kills Khamenei

Iran fired missiles at targets in Israel and Gulf Arab states Sunday after vowing massive retaliation for the killing of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei by the United States and Israel.

House Dem. Leader Jeffries responds to air strikes on Iran by U.S. and Israel

NPR's Emily Kwong speaks to House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY), who is still calling for a vote on a war powers resolution following a wave of U.S.- and Israel-led airstrikes on Iran.

Iran’s Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed in Israeli strike, ending 36-year iron rule

Khamenei, the Islamic Republic's second supreme leader, has been killed. He had held power since 1989, guiding Iran through difficult times — and overseeing the violent suppression of dissent.

Found: The 19th century silent film that first captured a robot attack

A newly rediscovered 1897 short by famed French filmmaker Georges Méliès is being hailed as the first-ever depiction of a robot in cinema.

‘One year of failure.’ The Lancet slams RFK Jr.’s first year as health chief

In a scathing review, the top US medical journal's editorial board warned that the "destruction that Kennedy has wrought in 1 in office might take generations to repair."