Bill Would Hold Back Third Graders Who Don’t Read Proficiently

A bill making its way through the Alabama Legislature requires that third graders read proficiently by the end of third grade or else be held back. The state consistently ranks near the bottom on national achievement tests in reading. Supporters of the bill say poor reading skills cause problems down the road.

More than half of Jefferson County third-grade students aren’t proficient in reading. In Birmingham city schools, it’s about three-quarters of third graders, according to the state Department of Education.

Rep. Terri Collins, who chairs the House Education Policy Committee and sponsored the Alabama Literacy Act, says holding those students back and giving them extra support helps them in the long term.

“You basically learn to read from pre-K through third grade. But after third grade, you read to learn,” Collins says.

The bill calls for the state to spend more on teacher training and early intervention.

About two dozen states have enacted laws similar to the one proposed in Alabama. In Mississippi, education officials say their students made dramatic progress when they invested more in early reading intervention and held back students who weren’t reading on grade level.

Collins says she wants the same for Alabama. Students who fail to master reading by third grade, she says, have trouble with other subjects such as science, history, and math.

“If we can address these needs when they are in kindergarten through third grade, we can help these students overcome those challenges,” Collins says.

Aquilla Fultz’s three children attend Jefferson County schools – one each in elementary, middle and high school. Over the years, she’s helped her children stay on track with summer reading camps, and she closely monitors their progress during the school year.

If you wait until third grade to intervene, you’ve waited too long, she says.

“If a student is having issues reading, they should have been held back before third grade,” Fultz says. “If you are seeing a problem in kindergarten, it needs to be caught and handled then.”

Some studies show holding students back puts them at increased risk of dropping out of high school. But Cari Miller, with the Florida-based education policy group ExcelinEd, doesn’t see it that way.

“It’s actually an opportunity for students that are severely below grade level to get the time they need with highly effective instruction by a highly effective teacher, to set them up to be successful in fourth grade where really the course work becomes much more rigorous,” Miller says.

Miller’s organization worked with Alabama lawmakers to develop the Literacy Act. She spoke last week in Montgomery at a public hearing where House committee members later approved the bill.

Sally Smith, executive director of the Alabama Association of School Boards, also was at that hearing. She says educators want reading achievement to improve, but they don’t want unfunded mandates.

“We don’t want to put mandates, when it’s hard enough to find teachers,” Smith says. “So we want to make sure that there’s a phase in to reach this and that there might be some flexibility if needed.” It’s unclear under the bill how much the state would allocate for reading specialists and early intervention.

Smith says programs — not policies — help students become better readers.

If the bill passes in the House, it moves onto the Senate for final approval.

Photo by the U.S. Military

Britain’s High Court says government illegally banned Pro-Palestinian group

In its ruling, the court said an earlier decision to ban the Pro-Palestinian group Palestine Action as a terrorist organization was "disproportionate."

On their way! 4 people on NASA Crew-12 mission launch to International Space Station

The four people are set to dock with the I.S.S. on Saturday, returning the orbital lab to its full complement of seven. NASA's last mission, Crew-11, left a month early due to an ill crew member.

‘Wuthering Heights’ celebrates mad, passionate excess — but lacks real feeling

Emerald Fennell's extravagant adaptation of Emily Brontë's classic cares little for subtlety. Ultimately, this love affair is more photogenic than it is deeply moving.

Can you medal in quiz? Go for the gold!

Plus: more Olympics, the Super Bowl and some monks.

Who will police Gaza, and how?

Under President Trump's Gaza ceasefire plan, Arab countries and the European Union are supposed to train a new police force in the Gaza Strip. But U.S. plans have run into serious challenges.

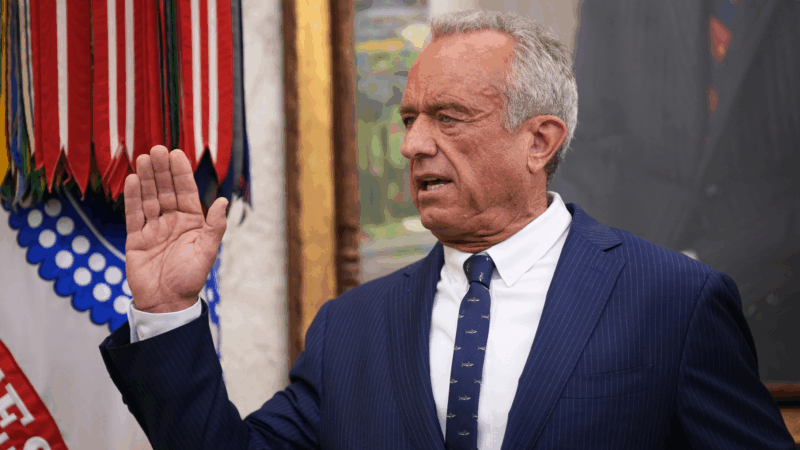

RFK Jr. made promises to get his job as health secretary. He’s broken many of them

In his confirmation hearings, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. told U.S. senators that he would not cut funding for vaccine research or change the nation's official vaccine recommendations. He did both.