State Looking at Plans to Fix or Replace Crowded, Crumbling Prisons; Lawmakers Don’t Expect to Be Part of Infrastructure Plan

By Mary Sell

Gov. Kay Ivey and the Alabama Department of Corrections aren’t yet talking publicly about possible fixes for the state’s crowded and aging prisons, but they are extending a multimillion-dollar contract with an outside project manager to study construction needs.

Some leaders in the Statehouse say they expect Ivey to move forward with a plan for new prisons that doesn’t require legislative approval.

“We’re going to have several prison-related bills (in the 2019 legislative session), but none will be infrastructure,” Sen. Cam Ward said recently.

He expects Ivey next year will begin the process to pay private companies for prison space.

“XYX company builds it, we lease it,” Ward, R-Alabaster, said. The new prisons would be staffed and run just like state-owned facilities.

Previous Plans Fell Apart in the Legislature

In 2016 and 2017, under former Gov. Robert Bentley, plans to borrow about $800 million to build several large prisons fell apart.

“Lawmakers are funny, they want new prisons and want to keep people locked up, but they don’t want to vote to pay for it,” said Ward, who sponsored legislation for new facilities.

Some lawmakers were concerned about losing prisons and jobs in their districts under plans to close existing facilities. There was also lobbying among legislators about where the new facilities would be located.

ADOC officials said then that the cost of building four mega prisons could be paid with money the state saved by closing up to 17 current prisons. New prisons wouldn’t totally solve the state’s occupancy issue, but they would have more modern designs and inmate monitoring systems and would be safer for prisoners and staff.

“The last session, the talk was that the governor had the ability to deal with prison infrastructure in her office,” Senate President Pro Tem Del Marsh, R-Anniston, said last week. “I’m fine with that.”

A spokesman for Ivey said her office isn’t able to talk about prisons at this time.

“There are ongoing discussions about possible plans but no singular final plan has been developed,” Daniel Sparkman said in an email. “We don’t expect a decision until the first of the year, January or February timeframe.”

Ivey previously has said getting a private company to build several large prisons to lease to the state is one option to solve the crowding problem.

She also has said she’s looking at options that don’t need legislative approval, which would include short-term leases.

Prison Studies Are in the Works

Last year, ADOC said it was seeking a company to develop a master plan for building new prisons and improving others. All correctional facilities, including minimum-security work release and work centers, would be assessed.

The agency is now extending its contract with Birmingham-based Hoar Program Management to $11.4 million, according to an agenda for the Dec. 13 legislative contract review committee meeting. That group of lawmakers meets monthly to discuss agencies’ contracts with private companies.

So far, Hoar has been paid $1.2 million, according to state records.

There are two other, lesser ADOC contracts for engineering design services on the agenda.

Last week, ADOC spokesman Bob Horton said the Alabama Prison Project Management Team, which includes Hoar, completed a thorough assessment of the prison system.

“The key components of the team’s assessment include the following: current and projected inmate population; current staffing levels and future staffing requirements; assessment of the prison system’s infrastructure and deferred maintenance cost; current operational costs and projected operational cost savings,” Horton said in an email. “The release of the team’s assessment of the state prison system is pending.”

Prisons Have a History of Problems

Crowding and unsafe conditions in Alabama prisons have been well documented.

Most recently, an inmate was stabbed to death and another was critically injured in separate incidents Sunday at a prison in Atmore.

In 2016, a guard was killed by inmates.

A facilities’ study released in early 2017 showed systemwide failures in the state’s 17 high- and medium-security prisons, most of which were built in the 1970s and 1980s. Problems included overused and outdated electrical systems and non-functioning fire alarms. In at least one prison, faulty locks on cell doors were a concern.

Last year, a federal judge declared mental health treatment in Alabama prisons to be “horrendously inadequate.” U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson cited “persistent and severe shortages of mental-health staff and correctional staff, combined with chronic and significant overcrowding,” in his 302-page ruling.

Ward, who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee that handles prison-related legislation, said proper staffing and health care aren’t possible in some of the current prisons.

“There is no way to run a mental health hospital in some of these facilities,” Ward said. “There is just no way to do that.”

The latest ADOC monthly report shows a systemwide occupancy rate of 150 percent. That number does not take into account dorms and beds added to prisons since they first opened. The Decatur Daily last year reported that when those additions are factored, the occupancy rate at major facilities dropped to 85 percent.

The department says the higher number is accurate because even though additional dorms may be added or common space is converted to living space, that doesn’t increase the infrastructure of a facility — things such as sewer and electric, security, programming and health care delivery.

Prison sentencing reform in recent years has helped lower the inmate population, Ward said. Previously, 35 percent of inmates were non-violent offenders. Now, it’s 14 percent.

“The worst of the worst are still left,” Ward said.

U.K. leader’s chief of staff quits over hiring of Epstein friend as U.S. ambassador

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer's chief of staff resigned Sunday over the furor surrounding the appointment of Peter Mandelson as U.K. ambassador to the U.S. despite his ties to Jeffrey Epstein.

Trump administration lauds plastic surgeons’ statement on trans surgery for minors

A patient who came to regret the top surgery she got as a teen won a $2 million malpractice suit. Then, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons clarified its position that surgery is not recommended for transgender minors.

Sunday Puzzle: -IUM Pandemonium

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with KPBS listener Anthony Baio and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

Thailand counts votes in early election with 3 main parties vying for power

Vote counting was underway in Thailand's early general election on Sunday, seen as a three-way race among competing visions of progressive, populist and old-fashioned patronage politics.

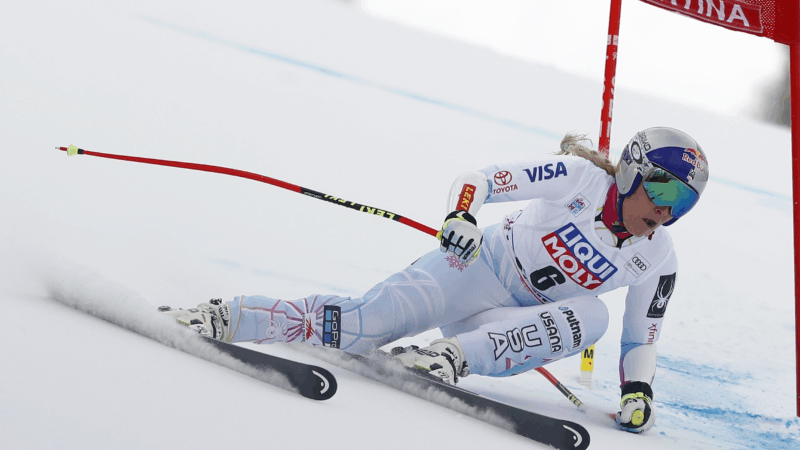

US ski star Lindsey Vonn crashes in Olympic downhill race

In an explosive crash near the top of the downhill course in Cortina, Vonn landed a jump perpendicular to the slope and tumbled to a stop shortly below.

For many U.S. Olympic athletes, Italy feels like home turf

Many spent their careers training on the mountains they'll be competing on at the Winter Games. Lindsey Vonn wanted to stage a comeback on these slopes and Jessie Diggins won her first World Cup there.