Museum Exhibit Gives a View of 1930s Birmingham

Walk through Birmingham of the 1930s and you would have seen buildings that are familiar to us today such as the four, early skyscrapers around the spot downtown known as the “Heaviest Corner on Earth.” But you would have also seen buildings that have long since disappeared, such as Terminal Station.

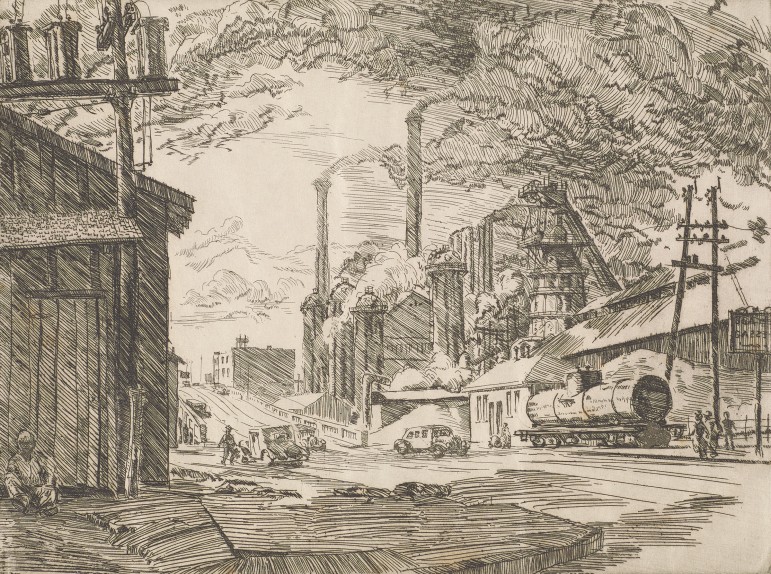

Images of these are part of a new exhibit at the Birmingham Museum of Art called Magic City Realism. The collection of etchings created in the 1930s by artist Richard Coe depict landmarks and everyday life of the city’s working class.

While some scenes may be familiar, Coe is a bit of a mystery.

“He’s not somebody who is really well known among American art historians or art historians more broadly,” says Katelyn Crawford, American art curator for the Birmingham Museum of Art. “Nobody’s worked on him prior to this exhibition.”

Coe was born in Selma in 1904. He studied in many cities including Cincinnati, New York and Boston. He also had a studio for two years in Florence, Italy. He lived in Birmingham from 1934 to 1939 and Crawford suspects he returned to Alabama because of a family connection.

“It’s a difficult time for artists and everyone in the mid-1930s and his grandmother lives here and he can live with her,” Crawford says.

Coe participated in Alabama Works Progress Administration projects, including painting a mural in the auditorium of Woodlawn High School in Birmingham. And while it’s a guess, Crawford thinks the etchings were probably for a federal project too.

The etchings feature recognizable views from the city skyline to steel factories.

“I really wanted people to be drawn into what people already know in Birmingham and start to pick that apart for them,” says Crawford. “Show them how Birmingham is not only very similar to what it was in the 1930s but has also changed dramatically.”

One of those differences is rundown housing in and around downtown that was quickly built to hold industry workers as the city boomed in its first few decades.

Crawford says it’s notable what Coe is depicting and what he leaves out. His etchings include blast furnaces, downtown buildings built by that wealth and gathering places for workers.

“But he’s not showing things like the Alabama Theatre or sort of high-end housing for people who owned the mines,” says Crawford. “It’s a very specific portrait of the city.”

Magic City Realism continues through June 17th.

The Birmingham Museum of Art is a program sponsor on WBHM, but the news and business departments operate independently.

Supreme Court strikes down Trump’s tariffs

The 6-3 ruling is a major blow to the president's signature economic policy.

The economy slowed in the last 3 months of the year — but was still solid in 2025

The U.S. economy grew 2.2% in 2025, a modest slowdown from 2.4% the previous year. GDP gains were fueled by solid consumer spending and business investment.

Ali Akbar, who’s sold newspapers on the streets of Paris for 50 years, is now a knight

For decades, Ali Akbar has sold papers on the Left Bank of Paris. Last month, France gave the beloved 73-year-old immigrant from Pakistan one of its highest honors — and his neighborhood is cheering.

Bill limiting environmental regulations goes to the governor’s desk

President Trump has taken steps to roll back environmental regulations. Some of that same action is taking place in statehouses, including Alabama's. Lawmakers gave final passage this week to a bill that would ban the state from enacting environmental rules more stringent than those at the federal level. That's where we start our weekly legislative update with Todd Stacy, host of Capitol Journal on Alabama Public Television.

For years the Taliban told women to cover up in public. Now they’re cracking down

At hospitals, at seminaries and on buses, the Taliban is stepping up enforcement of rules on women's dress in the city of Herat.

What I learned watching every sport at the Winter Olympics

Sit down with pop culture critic Linda Holmes as she watches the 2026 Winter Games. She is exhausted by cross-country, says "ow ow ow" during moguls, and makes the case, once and for all, for curling.