Why Metro Birmingham Homicides Are Up

Metro Birmingham had a streak last fall: eight killings in six days. The rash of homicides stretched from Hueytown to Homewood to Tarrant. The area’s murder rate rose in 2017 for the third consecutive year. Government and law enforcement officials in Birmingham and Jefferson County say there are challenges to what some have dubbed a crisis.

Sometimes, unintended targets are struck by bullets meant for someone else. And in many cases, the victim knows the suspect, like the case of Janice Hopkins Stamps in west Jefferson County. She died from gunshot wounds the day after this past Thanksgiving. Her brother, Tommy Hopkins told investigators he shot her when she was fussing at him.

Randy Christian, chief deputy in the Jefferson County Sheriff’s office, says guns and emotions can be a deadly mix.

“When you have guns available and people can’t control their emotions, that’s what you get,” Christian says. “ I think what happens, after it’s over, they wish they could take it back. But in those situations, there are no do overs.”

In 2017, 172 people died violently in Jefferson County, up 14 percent from the previous year. Most of those deaths were in Birmingham.

A.C. Roper, Birmingham’s outgoing police chief, says some challenges go beyond policing.

“Our unemployment rate is much too high. Our poverty rate is much too high. Our high school dropout rate is much too high. So our police department deals with the symptoms of those,” Roper says.

Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin says he wants to tackle issues like blight in the city’s highest-crime neighborhoods.

In the meantime, police departments are stretched thin. Roper says Birmingham is short about 100 officers. He says it’s been difficult to recruit replacements for retiring police.

At the same time, the 9-1-1- calls keep coming — about 50,000 a month. Not all of those are for violent crimes. But Roper says the city needs to be safer.

“No it’s not good at all. I think as a community we can do better. These type of things don’t happen in every community,” Roper says.

Birmingham City Councilman Steven Hoyt lives in Belview Heights in west Birmingham. He says for him and many other residents, the sound of gunshots followed by a call to the police is part of life.

“I hear them. I hear them often,” Hoyt says of the gunshots, “and I call often. But by the time they get there, they’re gone. I don’t know the answer to that, other than cameras.”

In Birmingham’s west precinct alone there were hundreds of violent incidents reported last year.

Hoyt says creating safe neighborhoods is a priority for the city council. The city spends almost $900 thousand dollars a year on ShotSpotters. Those are devices that detect gunfire and notify police. But the problem is, they are not everywhere. They cover only 20 square miles of the city.

In the past two years, the city has shut down more than a dozen clubs and stores that were crime hubs — like the Atlantis Entertainment and Event Center in Belview Heights.

“We revoked the business license for that place and the owner has chosen to just let the business stay closed,” Hoyt says.

Police say some crime initiatives are working — like the Metro Area Crime Center, or the MACC, based at the Jefferson County Sheriff’s headquarters.

Officers from more than 20 area police departments watch huge monitors that receive data from a dozen trailers with cameras strategically placed around the county.

Jefferson County Sheriff Captain David Thompson says they’ve caught some criminals in the act. That’s what happened last year when someone robbed a dollar store on Center Point Parkway.

“They ran right past our trailer, so we had good video footage of them. We had them leaving the store, so we actually identified and solved the case from here before the detective ever got out on the scene,” Thompson says.

That’s one time the technology worked to solve a crime. But much more often, it doesn’t work out that way.

Why farmers in California are backing a giant solar farm

Many farmers have had to fallow land as a state law comes into effect limiting their access to water. There's now a push to develop some of that land… into solar farms.

Every business wants your review. What’s with the feedback frenzy?

Customers want to read reviews and businesses need reviews to attract customers. But the constant demand for reviews could be creating a feedback backlash, experts say.

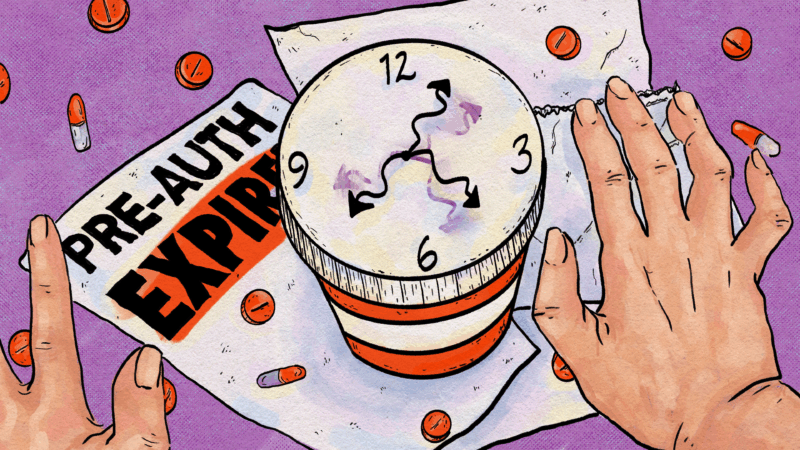

Can’t get a prescription renewed? Here’s how to cope with prior authorizations

These health care hurdles can stand in the way of getting treatment your doctor says you need. Here's what to know about how to deal with them.

‘Get back to integrity’: Oklahoma’s Kevin Stitt on Republicans after Trump

NPR's Steve Inskeep asks Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt about his spat with President Trump, immigration and the future of the Republican Party.

Civil rights leaders say the racial progress Jesse Jackson fought for is under threat

Activists say racial progress won by the Rev. Jesse Jackson is under threat, as a new generation of leaders works to preserve hard-fought civil rights gains.

Tariffs cost American shoppers. They’re unlikely to get that money back

After the Supreme Court declared the emergency tariffs illegal, the refund process will be messy and will go to businesses first.