Lack of Guidance Leads to Web Access Lawsuits

Almost three decades ago, the Americans with Disabilities Act required public places to accommodate people with disabilities — anything from installing ramps and elevators at schools to putting chair lifts in swimming pools. But back then, long before the Internet grew into what it is now, the law didn’t address the accessibility of websites. Now, with a proliferation of lawsuits, many companies are racing to bring their sites into compliance with industry standards.

These changes will almost certainly affect Joseph Walter. He’s a 23-year-old college student who takes classes online. He’s also confined to a special chair and a ventilator. He has limited use of two fingers and the thumb on his other hand. But his mind and his cursor are flying all over the internet, thanks to a special clicker and other modifications. I ask Joseph whether most websites are hard for him to use and his mother, Debra Walter, interprets his response:

“He doesn’t think they’re specifically accessible for him.”

And Joseph is something of a coding expert himself. He does research and shops online. And sometimes he tangles with websites that are hard for him to use, but he finds work-arounds on the fly. Many businesses are doing the same, as they scramble to make their sites compliant.

“This has gone from a requirement in a project to the most important requirement in a project, just really within the last two or three months,” says Mac Logue, creative director for Fitzmartin, a Birmingham-area marketing agency. He and other web-developers say that’s partly to avoid lawsuits as they try to make their sites accessible. How websites actually do that is evolving, and so are the industry guidelines that have become the de facto standard: the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, or WCAG 2.0. They’re basically industry best practices to ensure everyone can use websites.

“That includes people with no or low vision, people who may not have physical access to a mouse,” Logue says. “So, to be able to operate an entire website from the keyboard, say, or even a specialized keyboard that you look at but can’t physically touch.”

A site might also have to display captions when you hover over a video. All those are just a few of the needs to address. But the big question is, what is compliance?

In 2010, the Justice Department said it would issue guidance, but that hasn’t happened. Last year, more than 800 federal lawsuits were filed targeting businesses whose websites lawyers say were not accessible to people with disabilities.

“When the ADA was enacted, they did not think about things like websites,” says Leah Dempsey, Senior Director of Advocacy and Counsel for the Credit Union National Association. Credit unions around the country have faced dozens of lawsuits in recent months.

“There’s nothing under the ADA about what is necessary, but there [are] private industry standards. And that’s why there’s so much litigation out there. There’s a legal gray area.”

She’s holding out hope for clarity from the DOJ or from the courts. In the meantime, trying to bring websites up to standard is expensive. Depending on the site, that can easily range from $10,000 to $100,000. And legal fees can add tens of thousands of dollars more. The U.S. House of Representatives recently passed a bill giving companies a grace period to make their websites accessible, but the bill’s future is uncertain.

Logue says it’s in everyone’s interest to pay attention.

“You may not be getting sued today, but almost every business is going to be at risk at some point.”

Unless clear guidelines are issued soon, industry-watchers predict more legal battles.

‘Songs from the Hole’: The story behind JJ’88’s documentary and visual album

The visual album and documentary Songs from the Hole tells the story of James Jacobs, the hip-hop artist JJ'88, as he reflects on his coming-of-age within California's state prison system.

Oil price surges as Iran steps up attacks on ships in the Persian Gulf

Markets seesawed on Day 13 of the war in the Middle East, as two oil tankers were struck by projectiles near Iraq's southern ports and attacks between Israel and Hezbollah intensified.

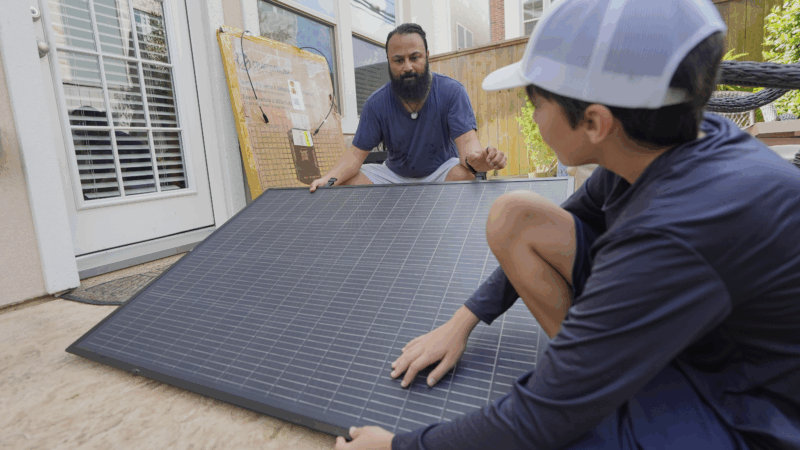

Easy-to-use solar panels are coming, but utilities are trying to delay them

Utilities are convincing lawmakers around the U.S. to delay bills that would allow people to buy solar panels, plug them into an outlet and begin generating electricity.

Trump’s war with Iran is angering some swing voters who want money spent at home

Swing voters who helped reelect President Trump in 2024 don't support his decision to go to war in Iran and instead want to see U.S. tax dollars spent tackling economic pressures facing Americans.

5 ways to resist the urge to keep looking at your phone

So you want to spend less time on your phone. How do you do that when it's designed to suck you in? Life Kit spoke to experts in behavioral science, psychology and technology for real-world advice.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrant truckers shifts into higher gear

The White House wants tougher rules for commercial licenses after several high-profile crashes involving foreign-born drivers. But critics say that would do little to make the nation's roads safer.