ALDOT Pitches Options for Little Cahaba River Bridge. Opponents Warn of Immediate and Permanent Harm to Drinking Water

By Hank Black

Traffic authorities seeking to extend a road across the Little Cahaba River in southern Jefferson County promised Tuesday to make it a controlled access road and prevent adjacent development in the watershed that protects metropolitan Birmingham’s drinking water supply.

But clean-water advocates poured into a public meeting Tuesday night to insist the risk of contaminating the river even from road and bridge construction outweighs the convenience of connecting Cahaba Beach Road to Sicard Hollow Road. Multiple environmental organizations are urging residents to lobby the state to drop the project.

The project would create a more direct route from U.S. 280 to future Liberty Park development and Grants Mill Road for an estimated 10,000 vehicles a day by 2025. But is not intended to reduce traffic on commuter-congested 280, according to DeJarvis Leonard, Birmingham region engineer, Alabama Department of Transportation.

The chairman of the Birmingham Water Works Board, which owns much of the property in the region, said it would request a hearing with ALDOT to learn more about the project.

“We don’t know what’s going on,” Tommy Joe Alexander said. “We have some of the best water in the country, and we want to keep it that way.”

Leonard said he also was seeking to set up a meeting with the water board to explain the project.

“We also would have to work through issues with private landowners and conservation trusts if the project proceeds,” he said.

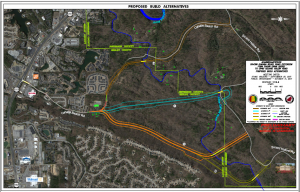

For several years, ALDOT and Shelby County engineers have sought to move the project forward. Last year, highway officials presented five optional routes across the river and asked interested parties to comment on the plans and indicate their preference for one of them or for a “no-build” choice.

The five routes extend from Swan Drive across the Little Cahaba to different points on Sicard Hollow Road. All still are under consideration, Leonard said, but two, known as routes 5 and 5-B, have been selected for traffic and environmental assessments and to show the nature of controlled access. The no-build option is also still on the table, he said.

Pollution Fears

Would construction of the road-and-bridge project in itself harm the Little Cahaba, which carries water from the Lake Purdy reservoir to the drinking water intakes below the site?

Leonard said it would not.

“We have ways of eliminating or mitigating construction activity so runoff won’t impact the waterway,” he said.

But the Cahaba River Society’s Beth Stewart said, “The project itself counts as major development – miles long, a 60-foot swath of land, grading, dirt-moving and a lot of pavement, with the river being the lowest point (where runoff would flow).”

Already, runoff from commercial and residential development in the area has resulted in significant sedimentation of the river, according to state studies.

Stewart, the group’s executive director, acknowledged that road builders now have improved methods of controlling runoff and spills.

“However,” she said, “You can reduce the impact of a road on the environment, but you cannot eliminate them. This will forever have an impact on the forest in the watershed that protects our drinking water. The forest will be degraded with a road, and we’re going to forever have an added risk of runoff contamination from the road and greater potential for accidents resulting in hazardous materials spills directly into our drinking water supply.”

In the fight against the project, Stewart’s organization has allies, including the Cahaba Riverkeeper, the Alabama Rivers Alliance and the Southern Environmental Law Center.

The rivers alliance is promoting a short documentary from the Southern Exposure Film Fellowship about the issues raised by the road proposal. The Cahaba River Society created a website to oppose the project.

While recommending against the project, the groups want ALDOT to consider making spot improvements along Sicard Hollow Road that would help traffic move more easily in and out of the back side of Liberty Park and reduce the need for an extended Cahaba Beach Road.

“We want to see (ALDOT) study ways to improve traffic and make it easier to travel through that area that don’t require a road that puts our drinking water at risk,” she said.

About 150 people attended the three-hour session at Liberty Park Middle School. Written comments about the project may be mailed through Aug. 22 to Leonard at 1020 Bankhead Hwy West, Birmingham, AL 35202, ATTN: Sandra Bonner, or by email to [email protected].

Note: The Southern Environmental Law Center is a sponsor of WBHM programming, but the station’s news and business departments operate independently.

Bill making the Public Service Commission an appointed board is dead for the session

Usually when discussing legislative action, the focus is on what's moving forward. But plenty of bills in a legislature stall or even die. Leaders in the Alabama legislature say a bill involving the Public Service Commission is dead for the session. We get details on that from Todd Stacy, host of Capitol Journal on Alabama Public Television.

My doctor keeps focusing on my weight. What other health metrics matter more?

Our Real Talk with a Doc columnist explains how to push back if your doctor's obsessed with weight loss. And what other health metrics matter more instead.

Baz Luhrmann will make you fall in love with Elvis Presley

The new movie is made up of footage originally shot in the early 1970s, which Luhrmann found in storage in a Kansas salt mine.

Forget the State of the Union. What’s the state of your quiz score?

What's the state of your union, quiz-wise? Find out!

A team of midlife cheerleaders in Ukraine refuses to let war defeat them

Ukrainian women in their 50s and 60s say they've embraced cheerleading as a way to cope with the extreme stress and anxiety of four years of Russia's full-scale invasion.

As the U.S. celebrates its 250th birthday, many Latinos question whether they belong

Many U.S.-born Latinos feel afraid and anxious amid the political rhetoric. Still, others wouldn't miss celebrating their country