Widening Rifts and Unfriending in Politically Tense Times

Have family gatherings been strained? Maybe you’ve unfriended people on Facebook or you’ve gotten the virtual cold shoulder for talking politics. You’re not alone. Thirteen percent of people, according to one survey say they blocked, unfriended, or stopped following someone on social media because of what they posted about politics. Haden Holmes Brown takes a look at tensions over politics three months into President Donald Trump’s time in office.

Stephanie Holden Smith, a stay-at-home mom of seven children, sits with her boys in the kitchen of their home in Shelby County, guiding the younger ones through their homework. Their white shaggy dog is stationed outside the back door, watching the boys’ every move.

For years, Stephanie has voiced her conservative views on Facebook. Her support of President Donald Trump is no secret to friends and family in person, either. But she’s noticed since the election, the tone of the interactions has become more personal, more aggressive.

“Several of my friends have actually de-friended me on Instagram or Facebook because of political disagreements. Those disagreements will turn to ‘you’re a hateful person, you’re a bigot, I didn’t realize you were a racist,”

Stephanie has tried to explain her views in what she calls a “non-emotional, factual” way. “They’re not really receptive to that. Several of the moms that I come into contact with won’t look at me in the eyes, and just have avoided talking to me altogether.”

Gene Smith—no relation to Stephanie—teaches here in Birmingham. He’s asked us not to mention his schools. He identifies as a liberal and since he’s become vocal about his views, things have turned icy.

“Almost all of my family and most of the people I knew when I was growing up have cut me out. Since this all happened, they have become totally alienated. It breaks my heart.

Almost three months into a Trump presidency, these fallouts over politics are still common, says Tina Kempin Reuter, director of the UAB Institute for Human Rights. Royter says avoiding these hard conversations allows people to shield themselves.

“If we only engage with our side, it’s very easy to only see this one perspective and only see one truth,” she says.

Reuter says it’s tough to take emotion out of the discussion and just talk about the facts. And with social media, you can’t see the writer’s face, so you have no context for how a person feels.

And what are the biggest risks for not having these hard conversations? Reuter has studied clashes abroad including the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the conflict in the Balkans. She says there’s similar underlying discord in today’s political climate here. The division among Americans might widen.

“And once that happens,” she says, “it’s so, so difficult to overcome the gaps between the two worlds because you don’t have common ground.”

Reuter says one way people who disagree politically can rebuild bridges is for them to share a meal. Eating together, she says, helps people see the things they have in common. But, Reuter says one thing is key: They need to actively listen to one another.

U.K. leader’s chief of staff quits over hiring of Epstein friend as U.S. ambassador

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer's chief of staff resigned Sunday over the furor surrounding the appointment of Peter Mandelson as U.K. ambassador to the U.S. despite his ties to Jeffrey Epstein.

Trump administration lauds plastic surgeons’ statement on trans surgery for minors

A patient who came to regret the top surgery she got as a teen won a $2 million malpractice suit. Then, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons clarified its position that surgery is not recommended for transgender minors.

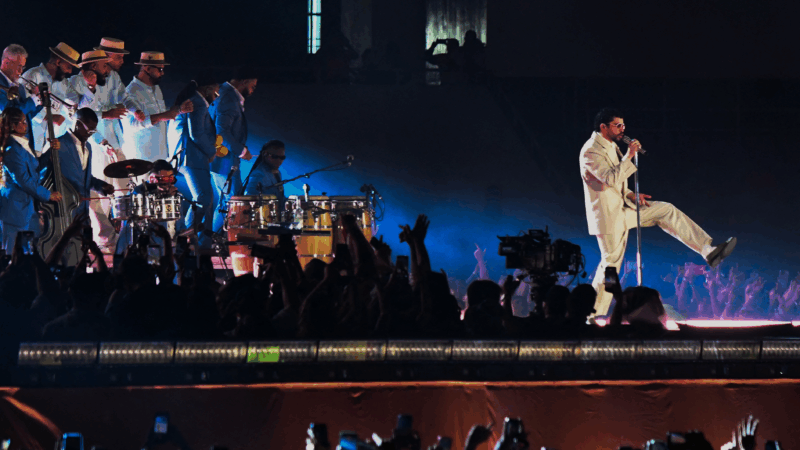

What you should know about Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show

Will the Puerto Rican superstar bring out any special guests? Will there be controversy? Here's what you should know about what could be the most significant concert of the year.

Sunday Puzzle: -IUM Pandemonium

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with KPBS listener Anthony Baio and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

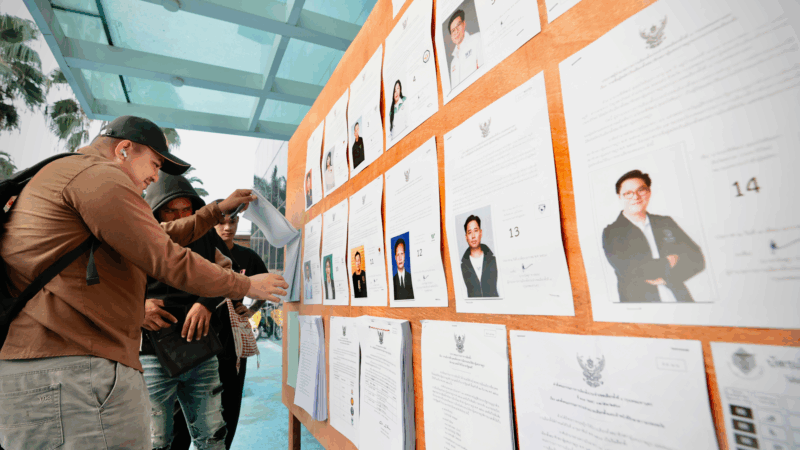

Thailand counts votes in early election with 3 main parties vying for power

Vote counting was underway in Thailand's early general election on Sunday, seen as a three-way race among competing visions of progressive, populist and old-fashioned patronage politics.

US ski star Lindsey Vonn crashes in Olympic downhill race

In an explosive crash near the top of the downhill course in Cortina, Vonn landed a jump perpendicular to the slope and tumbled to a stop shortly below.