NPR’s Joe Palca Takes On Jargon And The Politics Of Science

NPR science correspondent Joe Palca is in Birmingham helping UAB celebrate the anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birth. He stopped by WBHM, where sometimes-science-reporter and full-time-geek Dan Carsen jumped at the chance for an interview. They cover research bias, education, and science illiteracy. Joe starts by explaining why he does what he does. Listen to the on-air five-minute interview above. Its transcript is below. You can listen to an extended web-only version of the conversation below that.

[00:00:00, Joe Palca:] There’s this vast, fascinating, important world of science research that’s going on in this country and elsewhere that, A, people would be interested to know about. And B, they should have some knowledge of what it’s doing. And so I thought, science is a little off-putting to some people because they think, you know, “that’s really difficult stuff — I don’t know science.” And I thought … you know I took physiological psychology — I don’t know anything about physics or chemistry. But if I can understand it, I can explain it to you, and then you can understand it. So in that sense, I thought that science was just a piece of the world that I could do a good job explaining on the radio. And I like being on the radio. I’ve worked in print and I’ve worked in television. I like radio the best just because the pictures are better, as they say.

[Dan Carsen:] What’s your biggest challenge in reporting on science?

[00:00:49, Palca:] It’s the language and the jargon. If you open up the sports page, right, nobody’s going to tell you what an earned run average is. You either know it or you don’t. And it’s not even going to be “earned run average.” It’s going to be “ERA.” But every single time there’s some piece of jargon … I have to explain it. You have to keep backing up and backing up and backing up, and trying to keep things simple and not misleading. Scientists sometimes, you know, [they say] “you left so much out!” Well yeah. I’m talking for three and a half minutes on something that you spent two decades working on. Of course I left something out. The question is, did I leave out something that completely misleads the audience. That’s the tricky part. Not to do that.

[Carsen:] Is there a misconception that most people have about the real business of science?

[Palca:] Well, it sounds like people think that scientists have an agenda, which I sometimes think is a misconception. There probably are scientists who have an agenda. I mean most of the scientists I’ve met are people [laugh], and most of them, you know, they have biases and they have opinions like everybody else. But the whole notion of science is that you don’t bring those prejudices to the table — you go where the facts, the information, the data take you. Scientists in my experience are largely open minded and really delighted to find out when they’re wrong, because then they have to learn something new that will help them understand why they’re wrong.

[00:02:15, Carsen:] Many people — not to mention testing and polling on evolution and climate change, other basic concepts — many people point to scientific illiteracy in America. But at the same time we have some of the best research institutions in the world. How did this come about? What’s the weak link?

[Palca:] Well I don’t think they connect so much. We have some of the best athletes in the world and we have some of the most unhealthy people too. So I don’t think to say that the country is all physically fit just because we have great football players or great track stars or what have you. Similarly, I do think that it’s a shame that people aren’t more scientifically literate in general, but in particular, yes, we’ve got fantastic institutions of higher education, and yeah, there’s some bad schools in high school and middle school and in elementary school. There’s some bad ones but there are some great ones. And even in the bad ones, there are some great teachers. Yes, it would be nice, I think, if we valued sort of a basic [science] literacy, just like we value a basic healthfulness and physical fitness. But I’d like people to know that we have a bicameral system of government and that there’s three branches that are equal and independent and balancing each other, too. I’d like people to know a lot more about the world that they live in. So I’m not going to restrict it to science.

[Carsen:] Now that, right or wrong, science has become more politicized, what do you think researchers need to do to communicate their ideas to the public? Or should they even be expected to do that?

[Palca:] Well I do think they should be expected to do that. I have always felt that for a long time I was the conduit of that communication. And so any researcher that said he or she didn’t want talk to me, I would say, “tough. You’ve got to talk to me.” Well, they don’t have to if they’re privately funded — they can just tell me to take a hike. But any researcher who is publicly funded I believe has an obligation to talk to me as a surrogate for the public. So part two, “science has been politicized.” Well — and this is my opinion, not NPR’s opinion — I’m speaking for myself: I don’t think that the scientists have politicized science. I think the politicians have politicized science. So I think what’s important is for scientists to go out and say this is what we do.

[00:04:29, Carsen:] How do you see our divided politics and partisanship as affecting innovation across the country?

[Palca:] Oh, I think the great thing about innovation and especially invention is that, whatever your politics are, if you can invent a better chip or a better treatment or a better rocket or something, there’s probably money to be made there. And nobody is going to ask, you know, are you a liberal or conservative if you’ve got a pill that’s going to fix your cancer. I mean, yeah, let’s bring it on. I think that, of all the nonpartisan things that are out there, probably the most nonpartisan is the ability to come up with a good idea and make money off of it.

Below is the extended, web-exclusive version of the conversation:

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

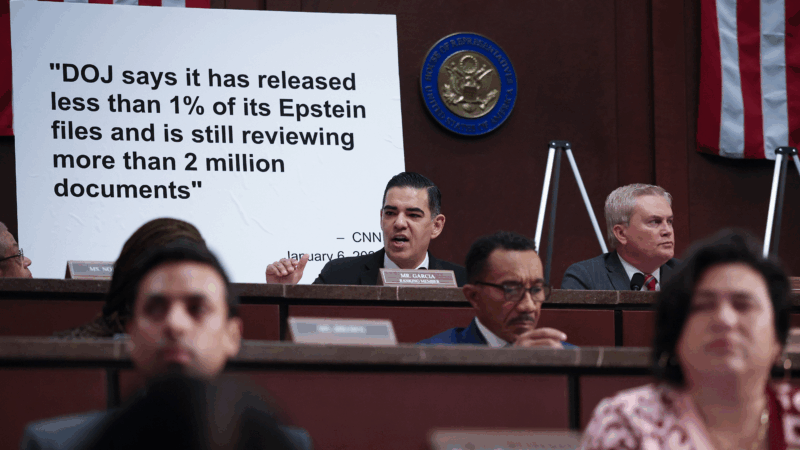

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

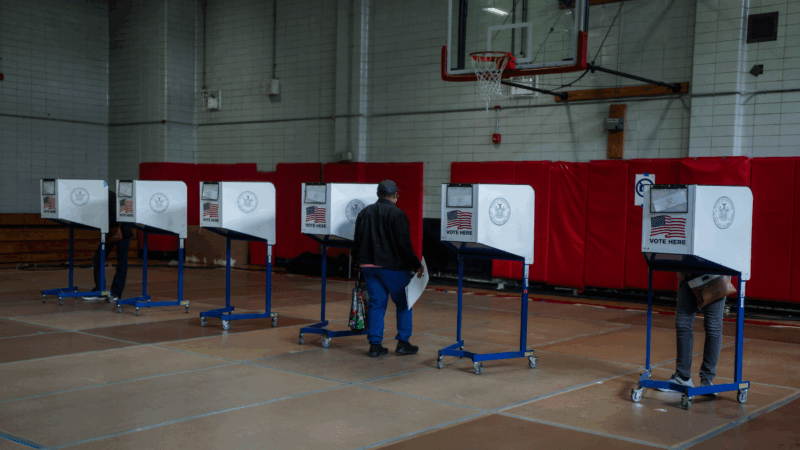

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.

Surgeon general nominee Means questioned about vaccines, birth control and financial conflicts

During a confirmation hearing, senators asked Dr. Casey Means about her current positions and her past statements on a range of public health issues.

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame 2026 shortlist includes Lauryn Hill, Shakira and Wu-Tang Clan

The shortlist also includes a 1990s pop diva, heavy metal pioneers and a legendary R&B singer and producer.