New Report finds Black Veterans Targeted for Lynching in the South

Hear an extended interview with EJI’s Bryan Stevenson below.

The Montgomery-based Equal Justice Initiative is building a memorial to lynching victims. The group estimates more than 4,000 African-Americans were lynched in the South between 1877-1950. Among those targeted were black veterans. These men returned from war abroad having experienced something unfamiliar to them: being treated with dignity and respect –– something they didn’t receive at home in the U.S. Many black veterans challenged the racial hierarchy of the South and were seen as threats to white supremacy. WBHM’s Esther Ciammachilli spoke with Bryan Stevenson, EJI’s founder and executive director, to learn more about the legacy of lynching and the history of racial inequality in America.

Ciammachilli: Why were white people concerned about the African-American veterans who were returning from war?

Stevenson: When World War I comes along and the country needs black people to help win this war and tens of thousands of African-Americans sign up to fight for the government, there’s a new threat to racial hierarchy. There’s a new threat to the sort of white supremacy that dominates political, social, and economic life because when these soldiers return after World War I and then certainly after World War II, they’ve now been exposed to a world outside of the emancipated South. They’ve been treated in many ways with dignity and respect. They’ve been armed, they’ve been trained, they’ve been disciplined, they’ve had success on the battlefield. And when you come back like that, you do pose a threat to people who are trying to create and sustain this world where black people only submit to whites, that they live in the margins, they get off the sidewalk when white people walk by. They don’t talk back. They don’t ask questions. They are subordinate. And so, targeting veterans and challenging any sense that freedom or autonomy or equality is something that they could expect meant that black veterans were experiencing racial violence at a much higher rate than other people, and the lynching of African-American veterans after World War I, after the Spanish-American War, after World War I, and then after World War II really points that out.

Ciammachilli: And of the thousands of blacks that were lynched in the South between 1877 and 1950, how many of them were veterans? Do we know that number?

Stevenson: It’s a hard thing to determine definitively because the reports about lynchings would almost always provide almost no information about who the person was and what their background was. Our research is increasingly suggestive that as many as 10% were people who had some prior military experience.

Ciammachilli: And did this violence against black veterans only take place in the South or was it more widespread?

Stevenson: It was more widespread. I mean the states that had the highest number of lynchings were all in the American South, but you would find you know these threats all over the country. I mean in the north and the west where millions of black people were fleeing to from the South in response to lynching. There were these growing numbers of African-Americans which of course created challenges and tensions in those communities. So, you would certainly see this and in the Midwest and Ohio and Michigan and Illinois in Indiana. You would see it in the far west –– California Arizona, the northwest, you’d see it in the northeast. It was more concentrated in the American South because the American South, of course, had a rigid legalized system of Jim Crow and of segregation. And black soldiers would be tempted to step across those lines. They no longer thought that it was appropriate that they have to drink out of a colored fountain, or go to an inferior bathroom, or to get out of the way just because a white person was walking down the street.

Ciammachilli: They challenged the white supremacy.

Stevenson: Exactly. That’s right. This narrative of racial differences, ideology of white supremacy, was something that I think black soldiers felt obligated to challenge having fought for American freedom and equality.

Success abroad was also enhancing that. You know black battalions fought valiantly in France during World War I and were highly decorated and recognized. The same was true of World War II. And to be embraced by these these embattled European communities and treated as heroes to then be treated as less than human as inferior and not worthy of any dignity or respect when they got back to the American South was very difficult to accept. And so there were tensions and conflicts emerging from that.

Ciammachilli: And you know I want to talk about actually what it was like for these men who enlisted to fight for the American freedom that they did not enjoy as civilians. What was life like for these men while they were in the military? Were they seen as equals by their white counterparts?

Stevenson: Well even in the military there was segregation, and that’s why this was a national problem, not just a southern problem. The United States military did not permit black people to serve alongside of white people. You know during World War I or World War II, but they fought so valiantly and effectively that it became harder and harder for the American government to justify this kind of segregation. But there’s no question that even during their military service they had to deal with racial segregation and racial separate separation. But I think there was still an affirming experience because they were armed they were trained they were empowered to do things that they could not do on domestic soil and then they had success. And I think that success really created a consciousness that, you know, we cannot continue to accept this white supremacy, this ideology that we’re somehow less capable. And you know there were many leaders in the African-American community that were urging black people to fight during World War I and certainly during World War II on the hope that valiant service, successful service, would then create payment from the American government of freedom of equality. It would ensure that the American government would do more to eliminate Jim Crow and segregation and to end the terrorism and violence that black people had endured since emancipation.

Ciammachilli: And you know speaking of emancipation and following the ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868, which states that all those born in the United States regardless of race are subject to the same “privileges and immunities” of citizens, following the passage of the 14th Amendment, several states actually made moves passed laws that essentially stripped certain rights from black veterans. Can you talk about some of those laws?

Stevenson: I mean, I do think that one of the challenges that we have in American society is that we haven’t really come to grips with how burdened we are by our history of racial inequality. I really don’t believe we’re free in this country. I think we’ve all been compromised. We’ve all been infected by this narrative of racial difference. I think our history of racial inequality has created a kind of smog that we all breathe in and it creates problems for us even today. It doesn’t take much to create distrust or offense or conflict. And I think that’s a product of our failure to deal honestly with this history.

I think we are a post-genocide society in America. I think what happened to native people when white settlers came to this continent was a genocide. And we haven’t done the things you’re supposed to do to recover from genocide, we had millions of native people slaughtered through famine and war and disease and we haven’t really addressed that. What we did instead was create this narrative of racial difference. We said, “Oh no, those native people, they’re savages. We don’t have to worry about their victimization.” And that narrative shaped the legacy of slavery. And as I’ve said, I don’t believe the great evil of American slavery was involuntary servitude or forced labor. I think the great evil of American slavery was the ideology of white supremacy. It’s the narrative we created to make ourselves feel comfortable owning other people we said black people aren’t the same as white people that got these deficits. They’re not fully human. And that problem wasn’t addressed with the constitutional amendments. They don’t talk about ending the narrative of racial difference or the ideology of white supremacy and because of that, you see states –– as you suggest –– creating local statutes and ordinances that are designed to prevent enforcement of rights under the 13th and 14th Amendment. And because of that, I don’t think slavery end in the 1860s, I think it just evolves. And the era of lynching and terrorism and violence that we witnessed in this country between the end of Reconstruction and World War II is dramatic evidence of that. There’s never been a time when you could see thousands of people gathering to witness a black man or woman or child being burned alive, being mutilated, being brutalized and murdered in the public square with no risk of prosecution.

Ciammachilli: As if it’s entertainment.

Stevenson: It was like a carnival. And the people didn’t wear a mask. People tend to think that this was violence committed by hate groups and the Klan. No these were unmasked leading citizens. It was often the elites, the teachers, the doctors, the writers, the people who were the business leaders of a community that participated in this violence and these mass atrocities were devastating to our commitment to the rule of law. And I don’t think we’re going to be a healthy nation until we acknowledge and recognize this legacy. When you go to South Africa, you can’t spend time there without being confronted with the history of apartheid. If you go to Rwanda they will make you listen to the stories of the genocide. Germany has created a new identity for itself by memorializing and marking the legacy created by the Holocaust. You can’t go a hundred meters in Berlin, Germany without seeing a marker or a stone that’s been placed next to the home of a Jewish family. The Germans want you to go to the Holocaust Memorial and reflect soberly on that history. But in this country we don’t talk about slavery. We don’t talk about lynching. We don’t really talk about the legacy of segregation. Here in Alabama, we’ve got hundreds of memorials and monuments honoring and recognizing the Confederacy. We romanticize that era. We celebrate Confederate Memorial Day as a state holiday. We celebrate Jefferson Davis’ birthday as a state holiday here in Alabama. We don’t have Martin Luther King Day we had Martin Luther King/Robert Lee day. And yet with this preoccupation with mid-nineteenth century history we do not talk about slavery. There’s no place in the state you can go and have an honest experience with the legacy of slavery. We don’t talk about lynching.

And so, our work is really aimed at changing that. We put out these reports about lynching and slavery. We’re going to build a museum here in Montgomery. We’re going to create a national memorial to victims of lynching. But we’re doing it because we want to create a different relationship to this history, not just for African-Americans, but for everybody. I think we will all benefit from dealing more directly, more honestly, more soberly with this legacy and we can change our identity too just as Germany has, just as Rwanda has, just as in South Africa. But we can’t do it by continuing to deny and resist efforts at confronting and acknowledging this troubling past.

In Vermont, small town meetings grapple with debate on big issues

Typically concerned with local issues, residents at town meetings in Vermont and elsewhere increasingly use the forum to debate polarizing national and international events.

Alabama man, on death row since 1990, to get new trial

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday declined to review the summer ruling from the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The decision paves the way for Michael Sockwell to receive a new trial.

Supreme Court blocks redrawing of New York congressional map, dealing a win for GOP

At issue is the mid-term redrawing of New York's 11th congressional district, including Staten Island and a small part of Brooklyn.

U.S. states take steps to guard against any potential threat from Iran

Iran has made prior attempts to launch terrorist attacks on U.S. soil, but all have been thwarted in recent years. States are bracing for a heightened threat after the war.

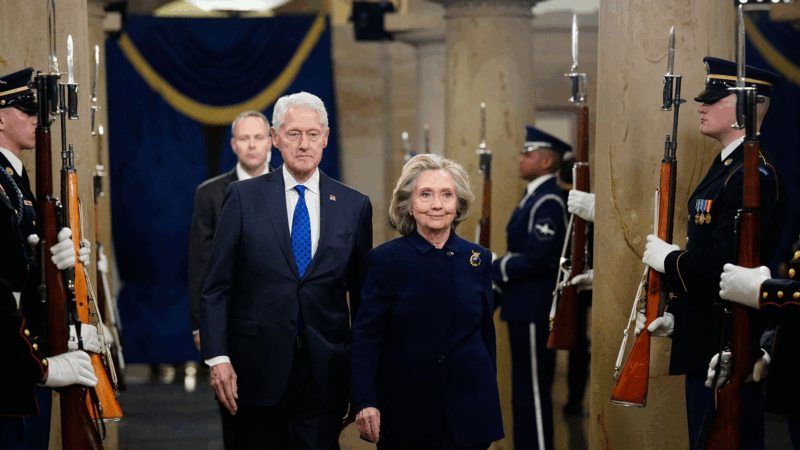

Video of Clinton depositions in Epstein investigation released by House Republicans

Over hours of testimony, the Clintons both denied knowledge of Epstein's crimes prior to his pleading guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl.

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.