When the Nation’s Top Polluter Drives a Small-Town Economy

Large industrial plants have big carbon footprints. The number one greenhouse gas polluter in the country is here in Alabama. Emissions from the coal-fired Miller power plant have the same climate impact as four million cars on the road. The ranking is according to 2015 US Environmental Protection Agency data, the most recent available. But many residents in the small town near the plant don’t seem concerned.

If you’re driving around West Jefferson looking for a place to eat, you won’t find much. On a recent afternoon, one restaurant came up in the search on my phone: Alabama Rose. My GPS leads me up a long gravel driveway where 78-year-old Arthur Graves lives. He pops open a beer and shows me what’s left of the restaurant.

The restaurant burned down a couple years ago. Three decades ago, Graves bought it, and the house next door, on his salary from Alabama Power, which owns the Miller power plant. It’s three miles away across the Warrior River. Graves retired as a boiler operator making $20 an hour. It was a good way to make a living, he says, and in West Jefferson, “It was the only option, really. Unless you wanted to fish and hunt for a living.”

Graves’ son and nephew went on to work for the power plant. Which might explain why before I turned on my recorder, he asked whether our conversation would get the Miller plant in trouble. “I draw a pension from the power company and my relatives and I… a lot of us, depend… we would not want to see the power company in trouble,” he says.

A recent report from the Center for Public Integrity showed Miller to be the top polluter for greenhouse gas emissions in the country: 19 million metric tons a year. That’s based on the company’s own data that they’re required to file annually with the EPA.

Jamie Smith Hopkins is a reporter with the Center for Public Integrity, which analyzed the EPA data. She says people care about things that affect their jobs or their health now – not the long-term consequences of carbon emissions. “It’s not something that that you know you can’t necessarily see in the same way that you can see the economic impact which is really important in our day to day basis,” she says.

Industrial sites that emit greenhouse gases tend to also put out other types of air pollution. Federal regulations have prompted Alabama Power to curb some of those toxic emissions. “At plant Miller, we’ve made close to $1.4 billion in investments related to meeting environmental regulations,” Michael Sznajderman, spokesman for Alabama Power says.

Those regulations cover traditional emissions, which the plant has reduced significantly over the past decade. But when it comes to carbon emissions, there are no rules.

“And one thing you don’t want to do is spend tens of millions or hundreds of millions or more trying to essentially meet a target that does not exist,” Sznajderman says. Carbon emissions at Miller have decreased 8 percent over the last 10 years, Sznajderman says. The Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan would have required power companies to cut carbon pollution 32 percent below 2005 levels by the year 2030. President Donald Trump in March ordered the EPA to scrap that plan.

Climate change isn’t something that worries people I spoke with in West Jefferson. Take Bobby Beckman, owner of the West Jefferson convenience store. He says climate change is a myth. “If something does happen to this planet, I won’t be around to see it,” he says.

Beckman says his business thrives on plant workers who come in daily to buy food and beer and cigarettes. He also rents furnished units for outside contractors who work at Miller. He lives three minutes from the Miller plant and he says he has no health issues. “You know there’s a dust issue,” he says, “but you know you’ve got a lot of things that contribute to that. You have Miller Steam Plant. You have railroad tracks not far from here. You have coal trucks running up and down the road, you know.”

But, he says, that’s ok. Everyone’s got to make a living somehow.

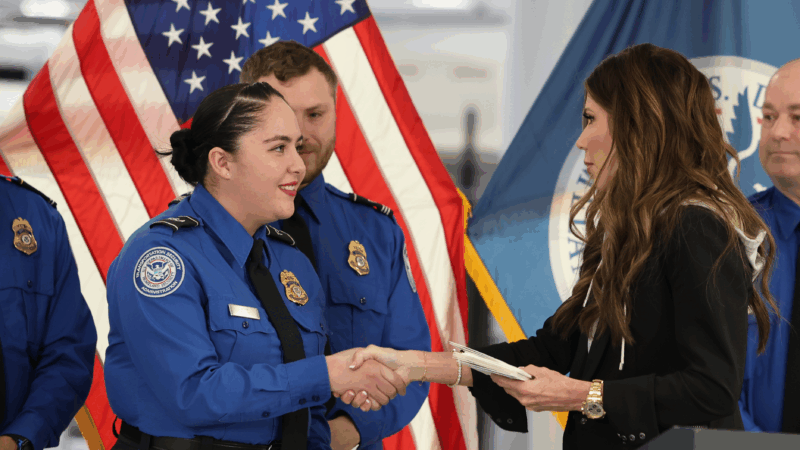

Homeland Security suspends TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is suspending the TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs as a partial government shutdown continues.

FCC calls for more ‘patriotic, pro-America’ programming in runup to 250th anniversary

The "Pledge America Campaign" urges broadcasters to focus on programming that highlights "the historic accomplishments of this great nation from our founding through the Trump Administration today."

NASA’s Artemis II lunar mission may not launch in March after all

NASA says an "interrupted flow" of helium to the rocket system could require a rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building. If it happens, NASA says the launch to the moon would be delayed until April.

Mississippi health system shuts down clinics statewide after ransomware attack

The attack was launched on Thursday and prompted hospital officials to close all of its 35 clinics across the state.

Blizzard conditions and high winds forecast for NYC, East coast

The winter storm is expected to bring blizzard conditions and possibly up to 2 feet of snow in New York City.

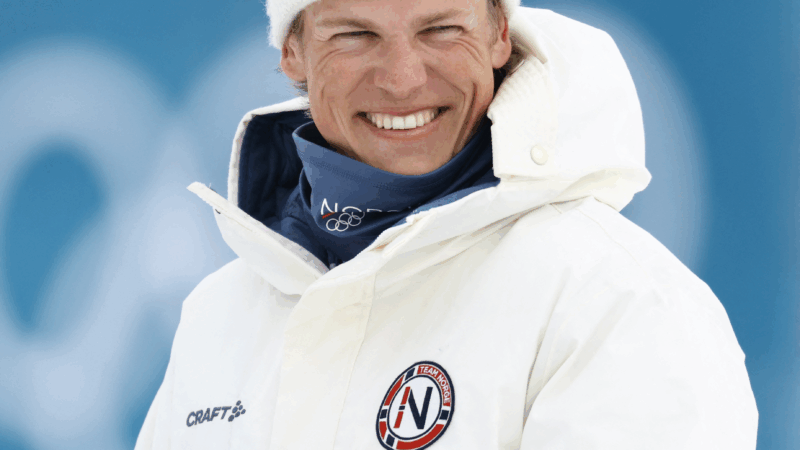

Norway’s Johannes Klæbo is new Winter Olympics king

Johannes Klaebo won all six cross-country skiing events at this year's Winter Olympics, the surpassing Eric Heiden's five golds in 1980.