Crime in Greater Birmingham: Literacy as Long-Term Prevention?

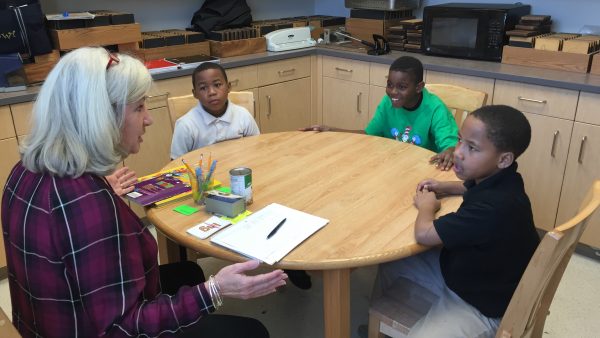

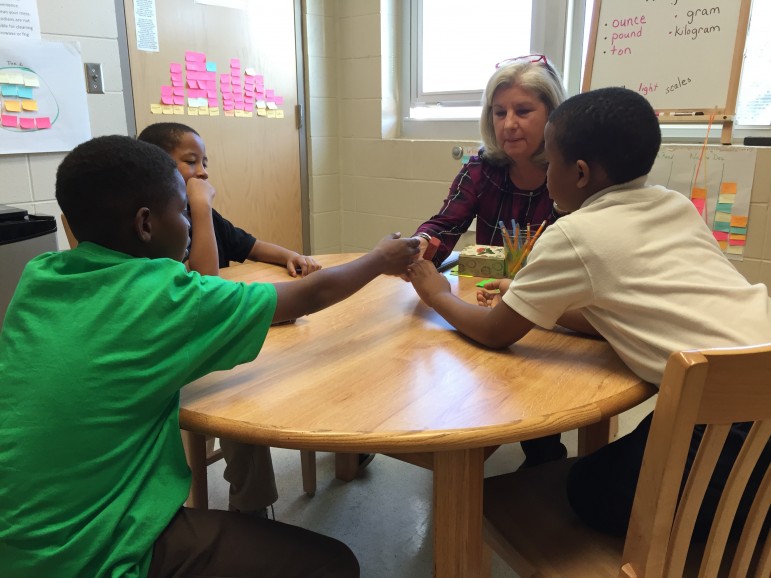

Left to right, Diane Wehby of Better Basics teaches third-graders Bryant McCune, Kantrell Clark, and Kamarion Morris at Washington K-8 in Birmingham.

Police and prosecutors try to fight crime in the streets and in the courts every day. But how do you fight the long-term root causes of crime? Some people think you do it in small school rooms like the one where Diane Wehby is teaching three third-graders at Washington K-8 in Birmingham.

Wehby is a reading intervention specialist for Better Basics, a literacy nonprofit. She worries about kids who don’t learn to read and fall behind in crowded classrooms because, as she puts it, “There’s a lot of research showing that … whatever scores they’re making on their national tests in second and fourth grade … that kind of tells where they’re going to be. Which is scary.”

Better Basics already works with several schools in high-crime areas. But next year, there’ll be a new reading intervention program at West Birmingham’s Minor Elementary, and it’ll be funded by a U.S. justice department Project Safe Neighborhoods grant.

“This isn’t about giving a kid a book and saying, ‘Okay, now don’t be in a gang,'” says Better Basics Executive Director Ammie Akin. “This is about developing a partnership with the local school system and saying, ‘Hey, let us put books in the hands of your children, let us send these certified teachers in, let us take this burden off the backs of your teachers who are already overworked and underpaid.'”

The word burden may seem strong, if you’ve never managed a full third-grade class with a few kids who read like fifth-graders and more who can’t read at all. And when the struggling kids fall through the cracks, there are wider implications. Akin points out that “85 percent of the [minors] in the juvenile system are functionally illiterate. And 60 percent of those in prisons are functionally illiterate. So the statistics are staggering. We know that we’ve got to teach people how to read.”

The federal grant will support Birmingham’s Violent Gang and Gun Crime Reduction Program for two years. Almost $300,000 will be split by the Mayor’s Office, the Birmingham Police Department, the state Board of Pardons and Paroles, the nonprofit Dannon Project, Better Basics, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where grant administrator Shelly McGrath has been mapping BPD crime data going back decades.

“The Project Safe Neighborhoods grant is basically looking to reduce violent crime in targeted areas,” she says, “but then also maybe take those approaches and apply them elsewhere in the city.”

Neither she nor Birmingham police wanted to talk tactics yet to be deployed, but Chief A.C. Roper says he appreciates the grant’s support for enforcement and for education.

“You have socioeconomic factors that impact crime,” says Roper. “If you can get a person educated and get them employed, their chances of committing violent crimes especially goes down tremendously. People who are working every day aren’t normally standing on the corner shooting.”

Akin agrees and says literacy can help keep kids off those corners. “We have to do something different,” she says. “And that’s what this grant is allowing Better Basics to do. We’re able to go in and help more children. The Birmingham Police Department has strategies to do things within the community to make the neighborhood safer. So it’s about a partnership, it’s about working together.”

The results of the programs are far off and hard to measure. But the Department of Justice and Birmingham police themselves are betting prevention includes cops … and teachers.

Bill making the Public Service Commission an appointed board is dead for the session

Usually when discussing legislative action, the focus is on what's moving forward. But plenty of bills in a legislature stall or even die. Leaders in the Alabama legislature say a bill involving the Public Service Commission is dead for the session. We get details on that from Todd Stacy, host of Capitol Journal on Alabama Public Television.

My doctor keeps focusing on my weight. What other health metrics matter more?

Our Real Talk with a Doc columnist explains how to push back if your doctor's obsessed with weight loss. And what other health metrics matter more instead.

Baz Luhrmann will make you fall in love with Elvis Presley

The new movie is made up of footage originally shot in the early 1970s, which Luhrmann found in storage in a Kansas salt mine.

Forget the State of the Union. What’s the state of your quiz score?

What's the state of your union, quiz-wise? Find out!

A team of midlife cheerleaders in Ukraine refuses to let war defeat them

Ukrainian women in their 50s and 60s say they've embraced cheerleading as a way to cope with the extreme stress and anxiety of four years of Russia's full-scale invasion.

As the U.S. celebrates its 250th birthday, many Latinos question whether they belong

Many U.S.-born Latinos feel afraid and anxious amid the political rhetoric. Still, others wouldn't miss celebrating their country